Blogs

Archives Month 2023: Taking a Second Look

By Michele Jennings

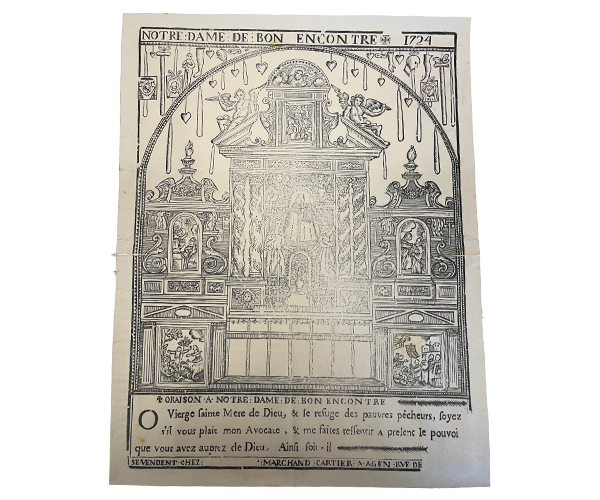

With American Archives Month coming to a close, I’m highlighting the multiplicity of meanings that archival objects take on by exploring the secondary value of a collection that itself is premised on creating multiples: The Notre Dame de Bon Encontre Woodblock Collection. The collection includes a wooden printer’s block created in the 18th century, as well as a more recent print created from it (the multiples), while the secondary value is demonstrated through the significance of the chosen woodblock technology to create the prints as well as the aesthetic choices of the printmaker.

While the collection offers insight into devotional practices and economies in 18th-century France, when I encountered this collection, I was struck less by its primary value — its practical purpose — than a potential secondary research application for it: the technology of woodblock printing at this place and time, as well as the composition of the print and its relationship to the spread of 18th-century French popular aesthetics, namely late baroque or rococo style.

To explain this secondary research application, first an extremely brief overview of printmaking technologies in the Western world. Two main methods exist for reproducing images through printmaking, not counting planographic techniques such as lithography or offset printing. Our Bon Encontre woodblock employs the first — relief printing, in which the printmaker starts with a block of a firm yet pliable material (in this case soft wood) and removes the material where the negative or blank space of the image will be. Rubber stamps are a type of relief printmaking tool, and woodblocks work very similarly: ink is applied to the raised surface of the block, and the image is transferred directly to the print. In the 16th century, relief printmaking was largely replaced in fine art prints with the second main method, intaglio, such as engraving, dry point, mezzotint, and other techniques. As the opposite of relief printing, intaglio allows the printmaker to “draw” or create a positive image, rather than gradually removing material to create blank space. In intaglio, metal sheets are incised with a tool or “bitten” out using acid that creates an impression of the positive image in the block. Ink is rolled across the surface of the block and wiped off the surface, leaving the unincised metal surface free of ink. As paper is pressed to the surface of the metal sheet, it picks up ink from the lowered, incised parts of the block to create the positive image on the print.

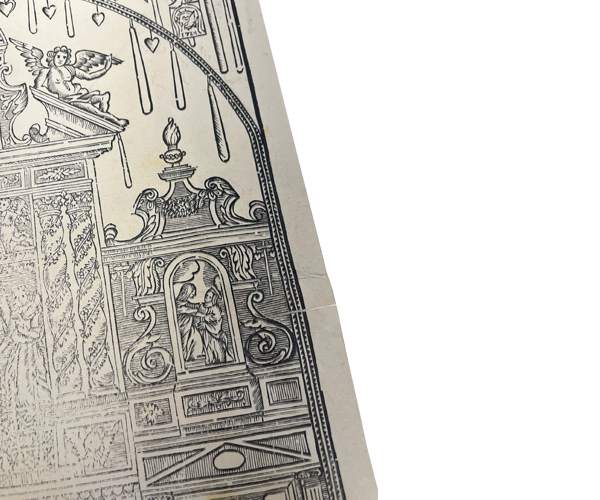

This understanding of these two major families of printmaking casts a new light on the Notre Dame de Bon Encontre Woodblock Collection. With the print itself and the much less common woodblock, the material process and technology of woodcut printmaking is not merely the belabored description you see in the paragraph above, but becomes knowable and understood through the materials of the print and woodblock. Examining the block puts one face to face with the labor of the printmaker, the minute carving to produce crosshatching (used to give dimension or shadow to the two-dimensional image), the way the center of the soft wood block has become worn from repeated use. That the image must be made in mirror also becomes apparent, and one wonders how many times this block was inked to produce so saturated and deep a stain in the block.

Knowing that this is a woodcut — and that it was produced in 1724 — produces another question: If intaglio printing was the accepted, most advanced printmaking technology a century prior, why a woodcut? The answer lies in the popular nature of the image as well as its intended audience. Woodcut printing was an affordable, relatively low-tech method to create prints for pilgrims’ everyday devotional use at a large enough volume and low enough cost to bring the shrine and/or printmaker a profit. Indeed, although intaglio was the top-of-the-line method for creating reproducible images from the mid-16th century, lower-cost methods still had a role to play in creating materials for reproduction and wide circulation.

Bearing in mind that the Bon Encontre print was intended for as wide an audience as possible, we arrive at another possible secondary research application for the print. In the composition of the print the Notre Dame de Bon Encontre shrine statue, scenes from Mary’s life and the history of the apparition, and various heavenly attendants are arranged in a sequence that resembles the facade of a building, with architectural details such as arches, columns and pediments dividing each montage. The architectural setting of the print’s imagery is richly decorated with scrolled, delicate tracery: filigrees and garlanded columns, classical cornices and broken pediments indicative of baroque and rococo architecture. In the 1720s and 1730s, the late baroque period became associated with rococo style in France, and for many contemporary viewers, this style is synonymous with French courtly splendor and the fusion of classical aesthetics with whimsical, organic forms.

In the Bon Encontre print, for example, the twisting garlands of leaves wrapped around classical columns that frame the central image are particularly indicative of late baroque or rococo style. The inclusion of these details in an object both sacred and part of everyday devotion suggests two points about popular imagery during this period: firstly, that even the most sumptuous of decorative arts styles could reach the masses through printmaking, and secondly, that this print served both a sacred purpose and an aesthetic one, bringing the day’s trends to any and all of the shrine’s pilgrims. Although rococo style was considered old-fashioned and fussy by the end of the 18th century, in 1724, the style was just emerging from the broader baroque period.

One of the most exciting things about working with archives — whether records, ephemera, artifacts or prints — is the way in which meaning shifts or activates through various readings, contexts, or simply the knowledge that the viewer brings with them. The Notre Dame de Bon Encontre Woodblock Collection has so many stories to tell–these are only a few!–and in its archival box it lies in wait, with endless potential. Although Archives Month is nearly over, the possibilities remain.

Further Reading

A few years ago, Andrea Bryan ‘19 wrote “A ‘Good Encounter’ with a Woodblock” for the Marian Library blog. The blog post offers a thorough discussion of what could be considered the primary value of the collection, or the purpose for which it was created. Printmakers would have carved the block and created prints from it to sell as souvenirs at the shrine of Notre Dame de Bon Encontre (Our Lady of the Good Encounter) in southern France. The post explains the role of the shrine for the local community; the practices around pilgrimage such as offering ex-votos; and the economic impact of devotional tourism and souvenir-making in Europe.

— Michele Jennings is a visiting librarian and archivist in the Marian Library.