Blogs

Incunabular Inscriptions and Doodles from Days Gone By

By Henry Handley

Faithful readers of past blog posts may remember that the term for a European book printed before 1501 is incunabulum, printed in the infancy of printing in the West. If a book can be anthropomorphized with a Latin word meaning “infancy,” its readers are likewise materialized in the marginal notes and illustrations they leave as a record. The notes and doodles that readers from hundreds of years ago leave behind can reveal a lot: their analytical skills; what they found important in the text; their creativity; even their boredom.

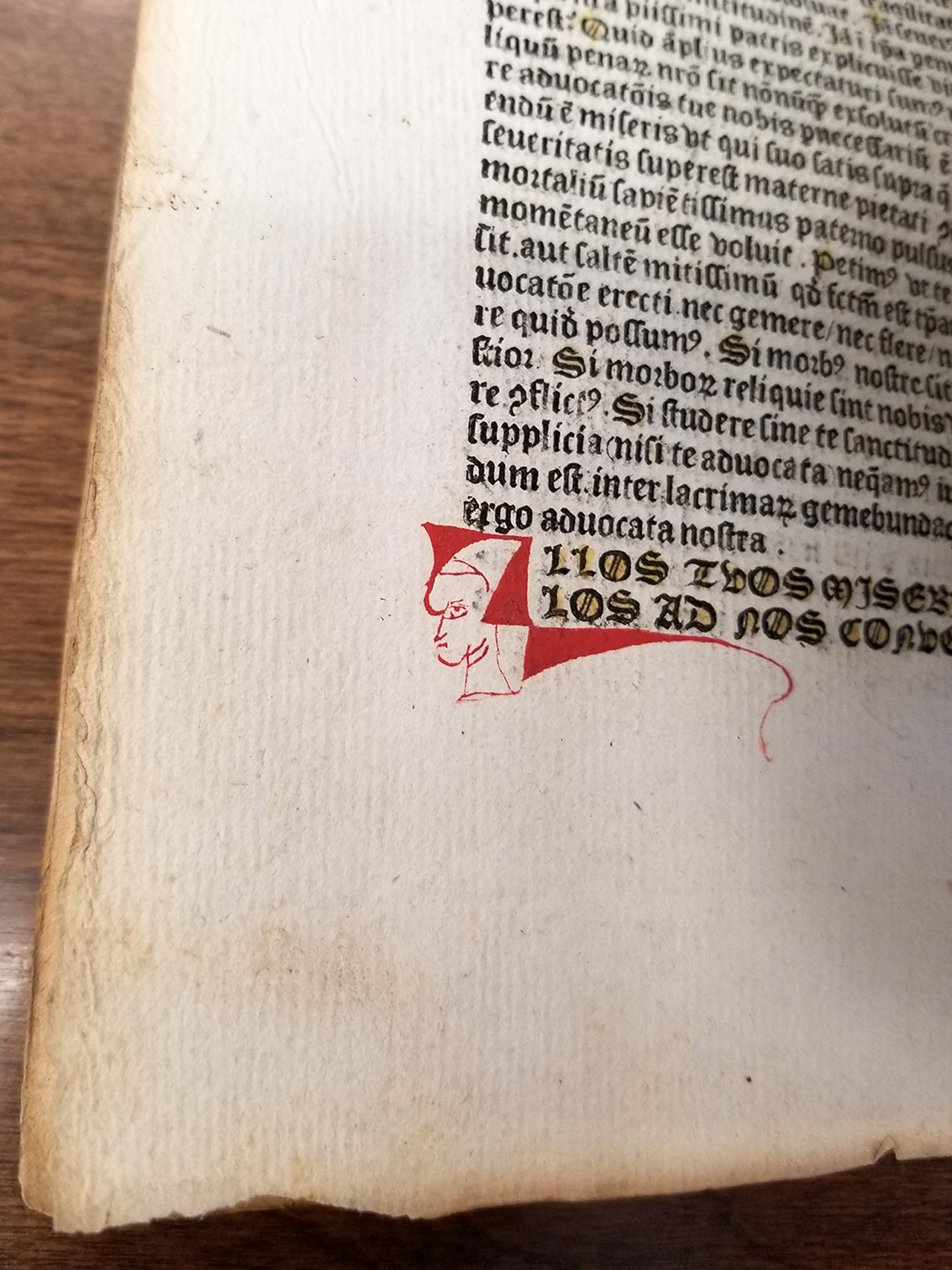

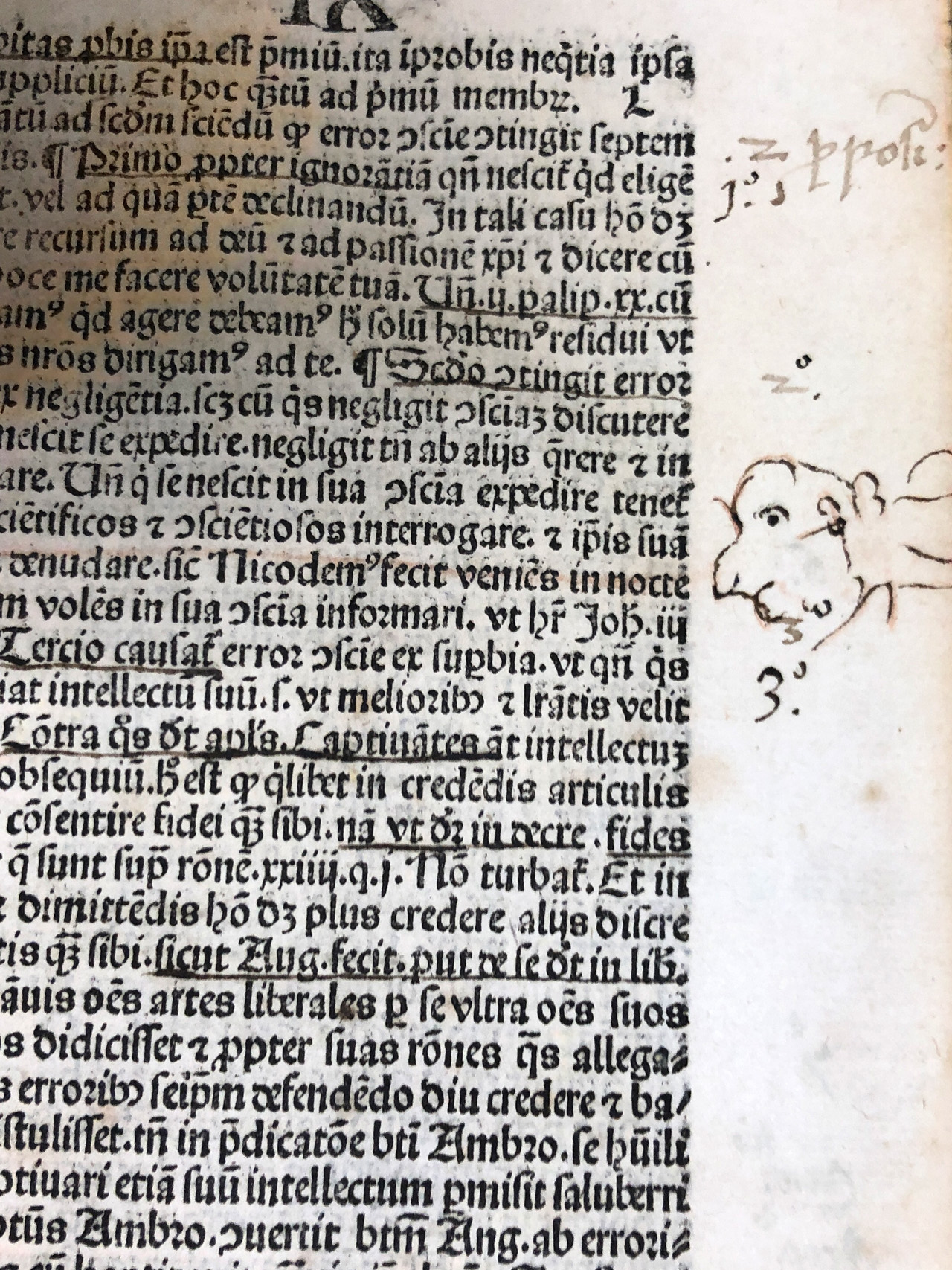

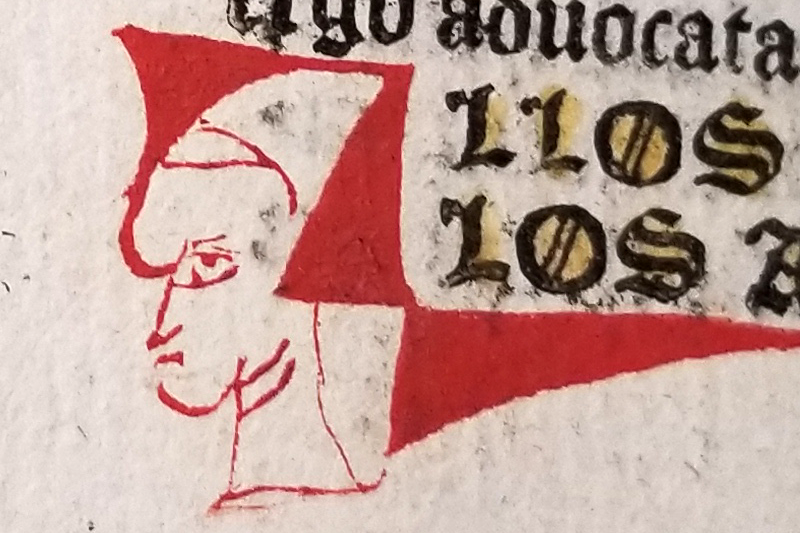

We don’t usually know exactly when these notes were taken or by whom. Handwriting may help narrow down an era or location or might match a former owner’s inscription. Some notetakers went farther and chose to draw in their books. Manicules — hands with extended index fingers — point out important parts of the text. Faces can serve a similar purpose; like fingers, noses might also be used to point to a particular line. On one leaf of music in the University Archives’ Beissel Collection, for instance, a nose points to the first note of a hymn.

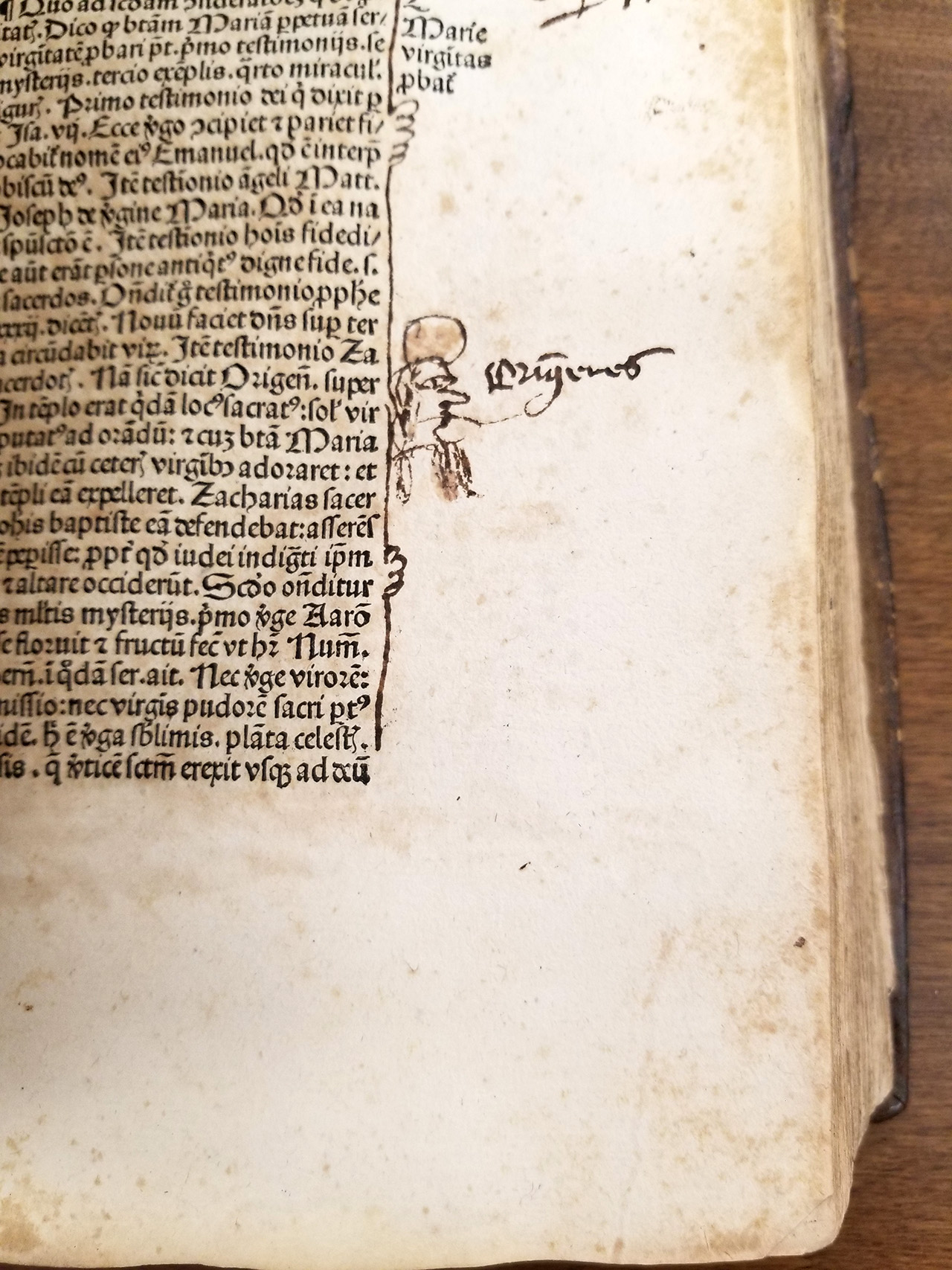

Without a clear connection to the text or a note from the artist, it’s unclear whom these portraits might depict. They could represent the reader, the author, a saint or scholar quoted in the text, or simply a grotesque that captured a distracted doodler’s attention. In Bernardino de Busti’s Marian sermons, one reader took the time to caption their rough portrait of early Father of the Church Origen with “Origenes” next to a passage quoting him. Other faces, like those drawn in collections of Marian meditations by Martinus de Magistris and sermons by Johann Herolt, lack names or clear connections to the text — but are perhaps more compelling for that.

What we do know is that these faces make the past more human. You may not read Latin; you might find sermons from half a millennium ago just a little dry. But when the book you’re looking at looks back? That’s a different story.

Have you just seen a face you can’t forget? Make an appointment to research rare books in the Marian Library by emailing marianlibrary@udayton.edu or calling 937-229-4214.

Additional resources

Wondering what q8r or b6v mean for the books above? They’re known as signatures, and each one indicates a specific leaf: the sheet of paper in a book that makes up two pages on the front and back. Printers included letters on these leaves to help bookbinders fold and put the printed sheets in order. Each leaf has a recto and a verso side; recto is the front, or right side of the leaf, and verso is the back, or the left. So “q8r” indicates the recto side of the eighth leaf of the section printed with a lowercase letter q. For more information, watch the first few minutes of Terry Belanger’s 1991 overview for the Rare Book School in “The Anatomy of a Book: Format in the Hand-Press Period.”

— Henry Handley is a collections librarian in the Marian Library. Special collections cataloger Joan Milligan also identified materials for this post.