Let's Talk Human Rights

Reclaiming Power: Insights from SPHR 2023 (Part 2)

By Robert Brecha

In November 2023, we gathered for the 2023 Social Practice of Human Rights, co-convening with the International Conference on the Right to Development, focused on the theme – “Decolonization and Development for Africa and People of African Descent.” This SPHR23 blog series captures the discussions and shares the learning that occurred during the conference around the themes of (1) the right to development; (2) building social movements; (3) just energy transitions; and (4) identity and belonging — as applied to Africa and the people of African descent.

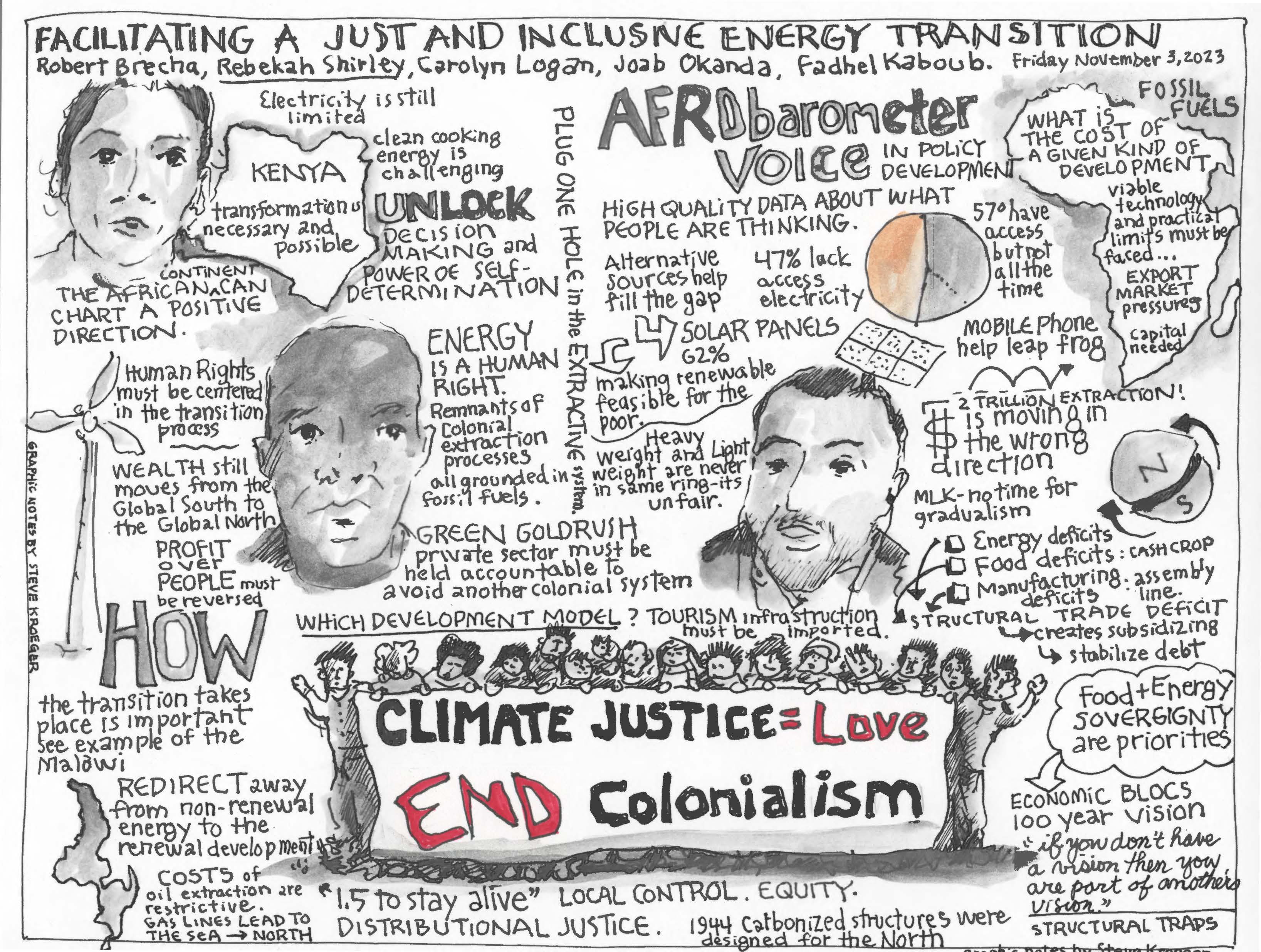

Facilitating a Just and Inclusive Energy Transition

We are approaching the one-decade mark from the historic year 2015 when the Paris Agreement was signed and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were agreed by most countries, and when Pope Francis published his encyclical Laudato Si’ – On Care for our Common Home. The confluence of these events gave real momentum to efforts necessarily linking climate change, development issues and rising global inequality. Although some progress has been made in the intervening years, the world has not sufficiently taken on the urgency of the challenge of mitigating climate change, and progress toward meeting the targets many of the SDGs has been too slow, and taken a significant hit through the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“1.5 to stay alive” was a refrain from the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) during negotiations that led to the Paris Agreement. That slogan was turned into the key goal of the Paris Agreement, that is, to make efforts to limit global warming to “well below” 2°C above the 19th century level and to make efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C. It has become increasingly clear over time both that there are significant differences in expected impacts from climate change at 2°C compared to 1.5°C, and that we are already experiencing severe climate impacts currently at a 1°C temperature increase. In fact, one of the first points made in the opening remarks of our Plenary Session during the Social Practice of Human Rights conference, given by Dr. Rebekah Shirley of the World Resources Institute, was that much of Africa has already seen above-average warming.

It is important to remind ourselves that there has also been a substantial effort put into mapping out the potential pathways for actually achieving the reductions in greenhouse gas emissions necessary to slow and halt warming and the associated impacts. The rallying cry of “1.5 to Stay Alive” may have been first made by AOSIS, but the group of Least Developed Countries (LDCs), many of which are in Africa, have large populations that are on the front lines of climate change impacts.

One important question concerning efforts to mitigate climate change, mainly by decreasing carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels to near-zero by mid-century, is whether this implied change to the energy system would be in conflict with goals for sustainable development. Fundamentally, access to modern energy sources (SDG 7) is not a goal in and of itself, but rather it is an important goal because access to electricity and clean cooking strongly helps enable achieving other goals, such as better health, education, productive employment, clean water, and more. Dr. Carolyn Logan, of Afrobarometer, stressed during the session that their survey research indicates that an important component in the energy sector is that there be actual productive use of electricity, not just access in theory. This idea of a “Just Transition,” making sure that vulnerable and developing countries are not left (further) behind by mitigation efforts, was the theme of our Plenary Session, with varying regional perspectives from Africa, the Americas, and the Caribbean

Dr. Shirley focused on the opportunities that could arise for Africa during the transition to a clean and green economy. The age structure of the population could mean a burst of entrepreneurial activity from younger citizens in new economic sectors compatible with sustainable development targets and climate change mitigation. A possible symbol of this optimism was the convening of Africa Climate Week, driven internally by leaders in Africa itself. Many of these leaders recognize not only that a young population could be turned to their advantage but also that one of the best ways to do so is by taking advantage of the wealth of “new generation” natural resources on the continent. By that, I mean renewable energy resources that can be harnessed first for internal purposes of development but which could also be the core of industrial development and even export opportunities.

This then leads to the cautionary note about the energy transition raised by Joab Okanda from Christian Aid, who emphasized two key points. First, that there is a tension within Africa, and between African countries, as to whether fossil fuels, and especially, domestic supplies of fossil energy, need to play a major role in development goals, before “worrying about” climate change mitigation. Okanda argues emphatically that it must be renewable energy that paves the way for both at once. As he put it, “My argument is that the Global North did not industrialize through fossil fuels, though fossil fuels contributed, the Global North industrialized through slavery, it industrialized through colonialism.” Thus, the path forward for the Africa that he (and other panel participants) envisions is based on a different model of building from the ground up a sustainable and climate-friendly energy system.

The second point he made, and this was shared as well in the comments by Dr. Shirley and Dr. Fadhel Kaboub, is that this new energy paradigm must avoid the potential for a new version of renewable energy colonialism. There is a danger that the extraction of mineral resources necessary for the global energy transition will become the focus of a new generation of extractive models of development based on the power imbalance between wealthier countries and the poorer countries of the Global South.

Finance flows are a key factor in enabling the energy transition. Unfortunately, these flows of capital are extremely imbalanced – away from South – to the tune of as much as two trillion dollars per year, as was pointed out by Dr. Kaboub. A fraction of these financial flows, now servicing previous debts, would be sufficient to catalyze the necessary investments for increased energy access, as well as mitigation and adaptation strategies. As Dr. Shirley also pointed out, the Continent only receives about 4% of global finance directed toward climate, while having a much higher, and growing share of the world’s population. Furthermore, and linking to the intersection of climate and development issues, it is in particular Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the greatest needs still exist for initial electrification and for access to clean cooking technologies.

The main takeaways from this session at SPHR 2023 were that there are both needs and great opportunities in Africa for carrying out a green energy transition. Over the past decade, learning effects, mainly in upper- and middle-income countries, have indirectly led to dramatic decreases in solar and wind energy costs. In principle, this progress should lead to investment opportunities in Africa, and not necessarily by relying on outsiders coming, but also for African businesses that would create jobs and retain earnings for the Continent. The focus here has been on energy systems, but the principles of the SDGs imply that a number of systems and targets be considered holistically. Looking at food and energy sovereignty, how to develop manufacturing capacity under local control, and how to transition away from a system that has been for too long dominated by structures remaining from a colonial past – all of these are challenges and opportunities that panelists emphasized in looking toward a brighter, greener future for Africa.

At SPHR, recognizing the urgency of the climate crisis, we advocate for a human-rights-centered approach to drive impactful change. This entails fostering collaborative partnerships across communities, disciplines, and organizations. By harnessing a broader range of knowledge and perspectives, we can develop effective solutions that address the crisis while amplifying the voices and work of groups least responsible for its emergence. In Laudato Si, the papal encyclical on environmental stewardship, Pope Francis writes, “The climate is a common good, belonging to all and meant for all…The notion of the common good also extends to future generations…We can no longer speak of sustainable development apart from intergenerational solidarity.” As President Eric Spina, in his framing remarks, reminds us, “sustainability and human rights — People and Planet—present an extraordinary opportunity for courageous, bold, sustainable and well-resourced solutions to the world’s energy demands. In this context, human rights are as important as ever to secure dignity, peace and justice for all on a shared, healthy planet.”

This panel was co-hosted by the University of Dayton Hanley Sustainability Institute (HSI).

Bob Brecha is Professor of Sustainability and Director of the Sustainability Program in the Hanley Sustainability Institute at the University of Dayton, with joint appointments in the Department of Physics and School of Engineering, Renewable and Clean Energy Program.

Plenary 3: Facilitating a Just and Inclusive Energy Transition

Social Practice of Human Rights Conference 2023: Decolonization and Development for Africa and People of African Descent

Social Practice of Human Rights Conference 2023: Decolonization and Development for Africa and People of African Descent

Plenary 3: Facilitating a Just and Inclusive Energy Transition