Blogs

Found in Translation: How UD Students Empowered Multilingualism in their Learning Spaces

By Hannah Jackson

Study abroad is an experience so enriching that we often hear students referencing their time abroad months and years after graduating. Don’t you wish your students would talk about your on-campus classes in the same way? Imagine: 10 years after graduation, your past student is dining with his family and his dad pops open a bottle of vintage Bordeaux. Your student says, “Wow, the rich yet subtle notes of this wine really remind me of the time my instructor tackled complex issues in their lecture on oligarchies.” Yeah, right.

While going abroad may not be an option for every course and every student on your roster, other forms of experiential learning can be. At the University of Dayton, we use a learning management system (LMS) called Isidore, which is based on the open-source Sakai LMS. This past term, French and Spanish Composition courses came on board for an experiential learning project translating hundreds of terms within Sakai’s user interface.

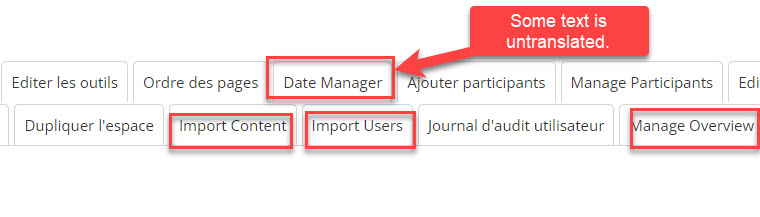

Because we use an open-source LMS at our university, the Center for Online Learning has a team of developers who work to craft tools and features that specifically suit the needs of our campus community. With the creation of new features, some of the words in the user interface are left only supported in English. So, even when a user switches their language setting on Isidore to Spanish, French, Arabic, or German, there will be words that still show up in English.

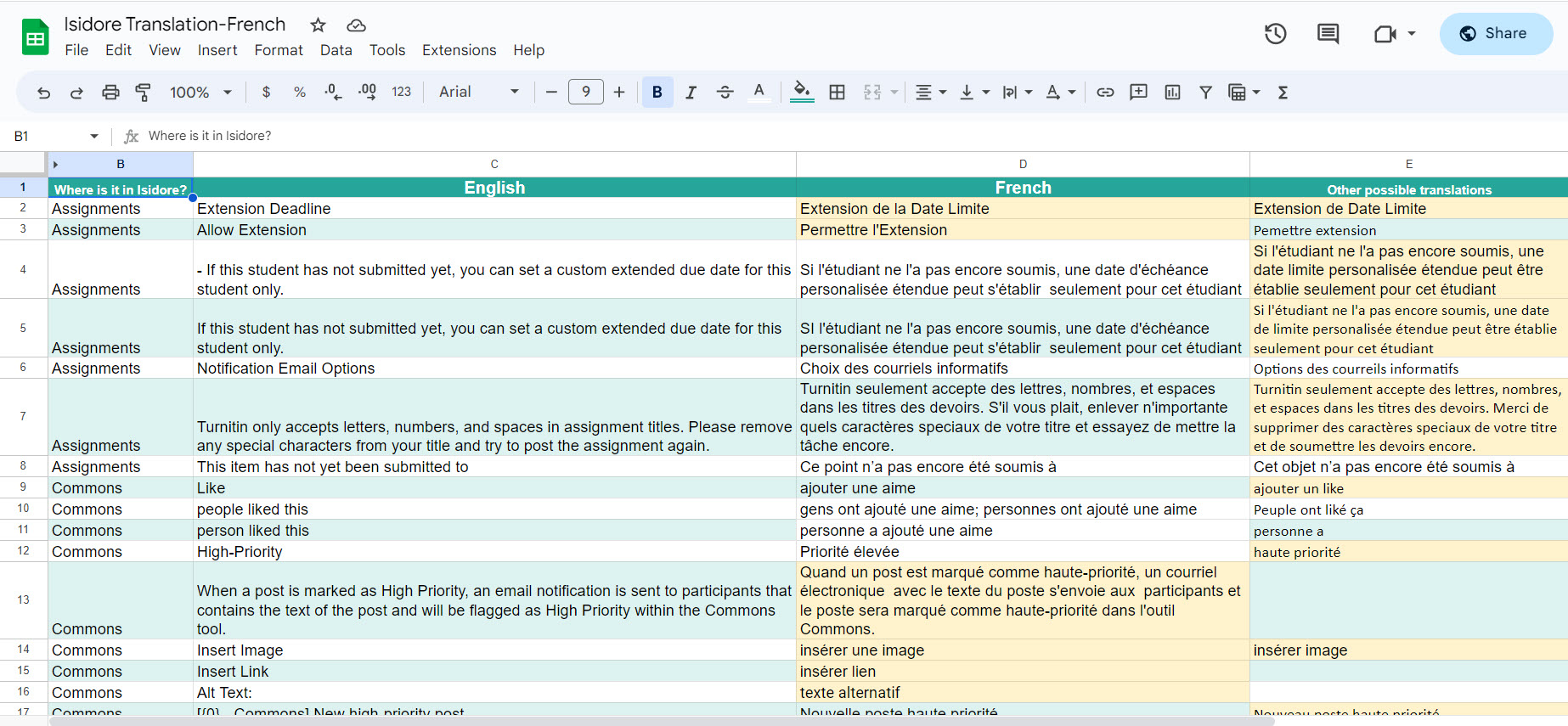

One of our developers, Joe, pulled these language “bundles” from Isidore, identifying which phrases, words, and chunks of texts were only supported in English. I took the Excel Spreadsheet full of language bundles and formatted it into a user-friendly Google Sheet with columns identifying where the text could be found in Isidore (in order to help students gather some context for their translations), a space to translate the text into French or Spanish, an area to leave questions regarding the meaning of the words in Sakai, a space for questions for their professor, as well as a checkbox noting if the translation had been approved by their instructor.

After meeting with a few interested professors, we deduced that our French and Spanish Composition students are at the requisite language levels to do this level of translation.

At the beginning of the term, I visited each class to introduce the project to students. The classes heard a quick presentation introducing the technical side of things and looking at some examples of the missing language bundles in Isidore. After showing the translation spreadsheet and the example Isidore course set up for students to access words in context, I answered a few questions and left the rest up to the students and instructors.

Classes broke up into groups of two to three students, though some individuals preferred to work alone. Dr. Costales, our participating Spanish professor, reported that she initially tried dividing up sections of text and assigning chunks to each group. After a while, she realized that students were finishing at different paces and stumbling around one another on the Google Sheet while trying to translate sections so close to other students on the document. Instead, she “turned them loose” and allowed the students to find their own method. And actually, this shift from teacher-led to student-centered learning is key with experiential learning.

Both classes shared that they jumped around the cells to find an area unoccupied by other groups to avoid overlapping and accidentally deleting someone else’s work. Some students preferred to find a section with short words that they were already familiar with, knocking out a large section of quick translations. Other students chose to hunker down and spend a long time working on a single translation that consisted of lengthy, technical text. I appreciated the freedom of the student process in the project. This student-centered approach allows for student agency and makes the project– with all of its challenges, successes, and lessons– their own.

Throughout the following months, I checked in on the Sheets and happily saw many little cursors working simultaneously. I would watch fly-on-the-wall-style as students actively translated in the document. Those of us at the Center for Online Learning were thrilled by the work being done by students, pulling our LMS out of the online space and into their classroom.

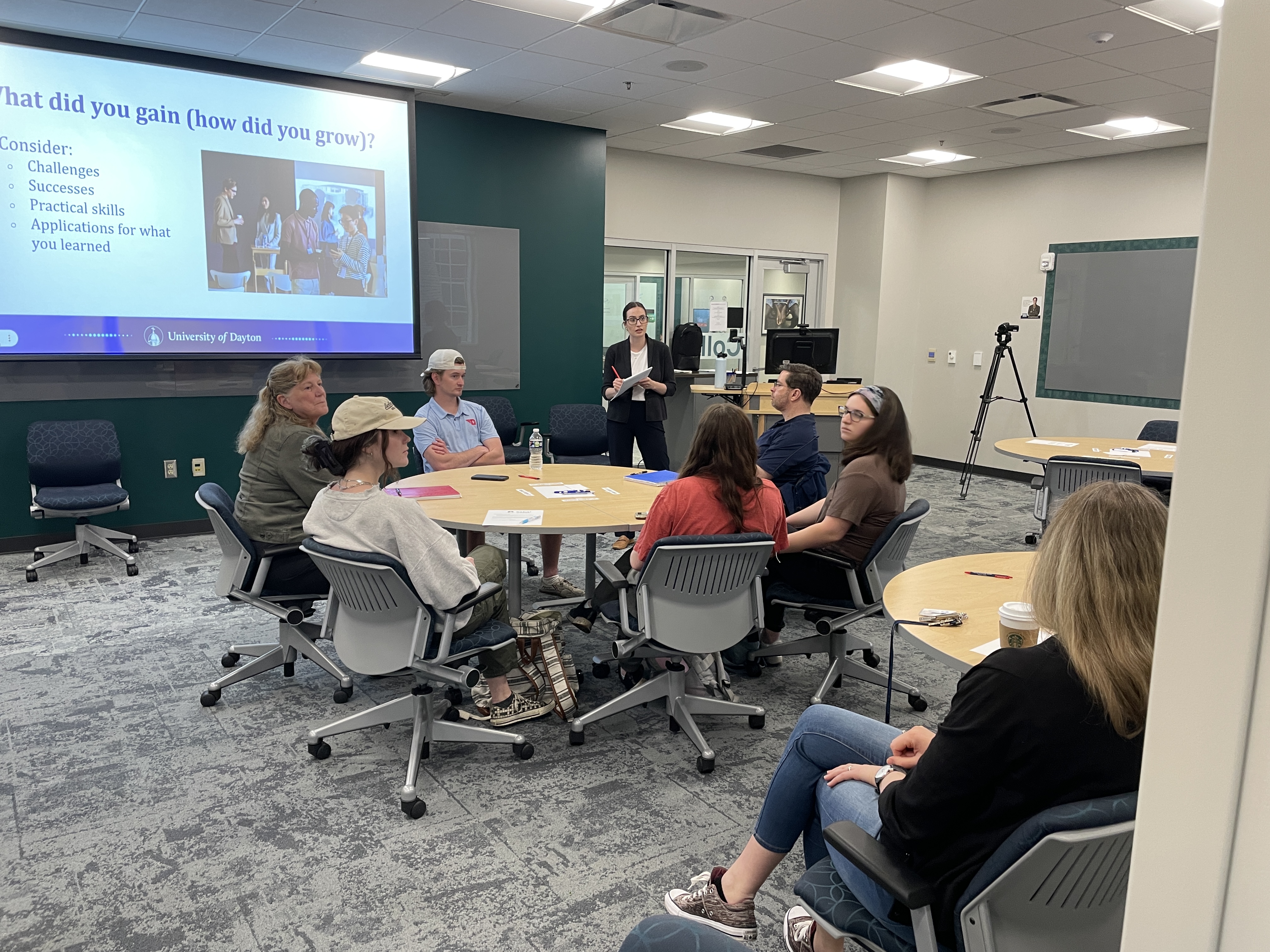

By the time finals were approaching, I scheduled a reflection session with both the Spanish and French students. Reflection is a core component of experiential learning, providing a space for students to synthesize and analyze their new experiences, problems they may have encountered, goals reached or not reached, and skills acquired. This piece of the process helps to situate the experience as something tangible and real.

During the reflection, I heard things from, “It was phenomenal to be trusted with the task,” to “I didn’t realize this project would be so far-reaching,” (referencing the large global community of Sakai schools who will benefit from the translations) to how important peer collaboration was for the success of the project. Students also expressed that the biggest challenge across the board was having enough context to complete each translation. Students told me they encountered moments of frustration when they came across a phrase they thought they knew the meaning of, only to try translating it and realizing the idiosyncrasies of meaning and utility that language is steeped in. They really grappled with the process of deeply understanding the meaning and purpose of a term before trying to translate it.

The project asked students to delve into the language of our open-source LMS, even though this group does not study computer science or programming and largely come from backgrounds in political science and international studies. They worked collaboratively to navigate the technical language, their existing knowledge-base, Spanish and French dictionaries, and the complicated process of rearranging syntax when word-for-word translation was not compatible.

Hear more from the instructors and students involved in the project in this video:

Students were presented with a practical challenge: take a spreadsheet of terms and translate them into Spanish or French. They reported feeling that the project directly helped them develop skills for their future workplaces, technical vocabulary that they don’t usually practice, and a chance to work with their chosen language in a deep context.

Our project’s French professor, Dr. Work, appreciated how this task made experiential learning accessible to each of her students. It was free and relatively straightforward to incorporate the project into the classroom and gave students an authentic French language experience. It can pose a challenge trying to find community partners in the area for French language experiential learning, so a project like this offers the whole class a unique language opportunity. Students could see the impact of their learning, which was authentic and rooted in a “real-world” task. At the end of only one semester, students translated 1049 terms and phrases into either Spanish or French.

Collaborative, hands-on learning does not need to be saved for grand trips abroad or intensive programs (as valuable as those things are). Experiential learning is as simple as identifying an area of need in the community and presenting students with the opportunity to problem solve. These students are the first in a group of translators to have impacted the online learning space at UD as well as the global Sakai community. Because of them, the LMS is more accessible and more complete.