Mary Immaculate, Patroness of the United States of America

Mary Immaculate, Patroness of the United States of America

– Reverend Richard J. Cushing

As the eighteenth century was drawing to a close, the thirteen English colonies along the North Atlantic coastline declared themselves independent and set up the sovereign nation of the United States of America. It was soon to become a haven for millions fleeing from poverty and oppression. The Catholic Church, up to then, unwelcome, distrusted and despised almost universally throughout the English colonies, was destined to take its place as one of the forces which would make the new nation strong and glorious.

The immediate reorganization of the Church in the infant republic so that it might function from Maine to Georgia was beset by great difficulties, many of them insurmountable for the moment. Father John Carroll, chosen for the task, accepted it reluctantly. He well knew that it was too heavy a burden for one person to carry, and he had little confidence in his own ability as an organizer and executive. He did possess, however, one unfailing weapon with which he always attacked every problem, his love of the Blessed Virgin and faith in the power of her intercession. With this weapon he began his career as bishop of Baltimore, his vast diocese which was co-terminous with the new nation. He was consecrated August 15, 1791, and in the first Pastoral Letter which he addressed to his scattered flock, May 28,1792, we read the following dedication of our country to the Mother of God:

"I shall only add this my earnest request, that to the exercise of the sublimest virtues, faith, hope and charity, you will join a fervent and well-regulated devotion to the Holy Mother of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ; that you will place great confidence in her in all your necessities. Having chosen her the special patroness of this Diocese, you are placed, of course, under her powerful protection; and it becomes your duty to be careful to deserve its continuance by a zealous imitation of her virtues and a reliance on her motherly superintendence."

In these words, Bishop Carroll called down the blessings of the Mother of God upon his fellow Americans in 1792 and placed under her patronage the Church in the United States from the first days of our national life.

The patronage of the Blessed Virgin over American territory did not begin, however, with the reorganization of the Church which was made possible under the changed political conditions of the post-Revolution era. It did not begin in the new republic at all.

The first official proclamation of it was made in 1643 by the King of Spain, and to this we shall refer again, but her patronage was implicit in the bull of Alexander VI in which, in 1493, he ordered the Spanish Crown in virtue of holy obedience to send to the newly-discovered lands learned, God-fearing, experienced and skilled missionaries to instruct the inhabitants in the Catholic faith and imbue them with good morals. The Holy See endorsed Spain's claim to the whole western hemisphere with the exception of Brazil under these conditions. Our territory remained within this claim until other European nations successfully challenged it, and our history was Spanish colonial history for over a century in the East, for much longer in the West.

Most phases of American history should be viewed from continental or hemispheric beginnings to be understood completely. This is notably true in the story of the patronage of Mary. In that story there is no real break between the arrival of Christopher Columbus and our own day. An eminent historian of the Church, writing about Marian devotion in our country as of a century ago, makes the following comment:

"When the call came from the Holy See for the bishops of the world to assemble at Rome for the solemn pronouncement of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in 1854, the Catholics of the United States could bring with them to Rome three centuries of devotion to Mary Immaculate as their offering to the Mother of God." [Source not provided.]

Bishop Carroll, in his Pastoral Letter of 1792, had only to renew and re-assert the patronage of Mary which the Spanish had invoked first when they embarked upon the missionary venture of converting the native peoples of the hemisphere and later, specifically in our national scene, when they settled along the Florida coast in the mid-sixteenth century.

Devotion to the Mother of God is as old as the Church and is inextricably woven into the fabric of Catholic life. It began in the Cenacle and followed the spread of Christianity into Europe and then beyond into other continents. It was spread to the ends of the earth by the missionaries of the Age of Exploration. Wherever Christ Crucified was preached, there also was preached Mary's part in the Incarnation. The missionaries whom Spain sent to America were in a most advantageous position. Here it was not a question of setting up the Church to function within ancient civilizations, as in Asia, but rather of creating a whole new Christian society. There was to be no cleavage between spiritual and temporal interests; both were to be resolved within a Catholic whole. America was to be the extension of Christendom. Mary, queen and patroness in all parts of Christendom, would be queen and patroness here.

The Spaniards who discovered and explored, converted and civilized America, beginning with the little band who sailed on the "Santa Maria," were men into whose culture were woven the golden threads of centuries of intense Marian devotion. They understood Christian unity in terms of the Incarnation. They practiced Christian discipline in the name of Christ and His holy mother. They, or their associates, had walked as pilgrims, contrite for their sins, to shrines built to Mary: to Saragossa, to Monserrat, to a score of other Marian shrines still popular in Spain today. All their lives these men had listened to the earnest pleas for the promulgation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception which were general in Spain, as in the rest of Europe, all through the later Middle Ages. Canons deliberated on it in their chapters; theologians in university halls, humble unlettered groups had mused on it as they sat sunning themselves in the soft music of the fountain in the village plaza.

The task which confronted those men, giants of the sixteenth century, of incorporating multitudes of primitive peoples into the body of Christendom was unprecedented in difficulty. They must learn hundreds of languages and create in each of them a new vocabulary to make Catholic theology a living force. The grades of civilization among aboriginal peoples varied from nomadic barbarism to relatively high primitive culture, their religion from ceremonial dancing to orgiastic rites and human sacrifice. How would the Spaniards proceed to make Christians out of these heathens? Picture them, aghast at the utter paganism they beheld. What would they do? They would build new Saragossas. They would teach the gospel of the Word Incarnate and they would share their Mother.

We could follow them, priest and layman, up and down the paths of two continents. We could accompany them as they trudged along under the heavy weight of supplies and the yet heavier burden of conscience to convert these Indians into temples of the Holy Spirit. We could list their names and find within them all the name of Mary. We could trace on the map cities and mission towns, rivers and lakes to which they gave the name or a title of Mary. But in the end we should have done no more than collect evidence for what we could not fail to know beforehand: that in their program of Christianization, Mary would play a major role. Through her they would petition for the wisdom they needed; in her they would hold up the model of Christian living.

Four centuries later, Latin America still proclaims the success with which these missionaries and colonizers worked. Though anti-religious laws have often been passed by governments hostile to Catholicism in various nations since their independence from the mother country, the thinking of the people on family life, for instance, continues to reflect the Catholic principles upon which their society was built. Likewise, the love they bear the Mother of God has never decreased in fervor. One of the indelible pictures which tourists bring back from visits to Marian shrines is the memory of devout men and women, oblivious of the march of tourists, rapt in prayer, making their way on their knees, flowers in hand to lay at the feet of Our Lady. One of my own strongest impressions in meeting bishops from Latin America, in my work for the Propagation of the Faith, was their perfect confidence in the love of their people for the Blessed Virgin.

Many of the shrines of Our Lady popular at the present time in America date from the arrival of the first European. It does not seem an exaggeration to say that the trail of the pioneer was marked by some image of' Mary left at each new frontier. The colonial shrines to Mary in our own territory, as elsewhere, have never been known in their totality. Chance reference in the letters of missionaries to shrines otherwise unknown make certain that she was everywhere. In the beginning, shrines were of the familiar European madonnas, Our Lady of the Snows, Our Lady Refuge of Sinners, Our Lady of Sorrows, etc. Soon native madonnas came into existence. At almost the same time that the madonna of the Italian Renaissance was appearing Europe with distinctive German, Flemish, Spanish features, she was endowed in America with the native cast of countenance of the Indian.

Rather than attempt to enumerate or describe the known shrines of Our Lady which date back to colonial times, let us look briefly at two from among them which are clear illustrations of certain patterns in the Marian devotion of that era: Our Lady of Health and Our Lady of Guadalupe. Devotion to both of these Madonnas penetrated into the territory of our Southwest, which depended on the viceroyal government of Mexico City. Both show not only that the Blessed Virgin was mother of the individual and of society after conversion but also that she was a powerful force in the conversion itself. It was she who was La Conquistadora.

Let us take the less well known, Our Lady of Health, first. She is a preeminent example of the assistance Our Lady gave to the administrators of a region in making aboriginal people citizens of Christendom and sharers in the civilization of the West. Her shrine is in the diocese of Michoacan, to the west of Mexico City. It was erected by the first bishop, the famous Vasco de Quiroga. The Indians of Michoacan, the Tarascans, were nomadic and impatient of all restraint.

The bishop, in whose hands the entire project of civilizing the people was placed, set up the means and paraphernalia of civilization: the Church, hospital, asylums, workshops and tools, and the framework of administration. He laid out a hundred towns in a planned economy. He took every precaution to assure equity and justice, and he worked to develop their love of one another as children of God. He taught them about their Holy Redeemer and about His blessed mother. He erected the shrine of Our Lady of Health, through whose intercession they were to strive for health of soul and health of body. Every advance they made in virtue, every effort toward decent habits of hygiene and sanitation they were to offer as flowers in a garland to La Purisima.

The statue which represented Our Lady of Health came from Europe. The Indians cherished it. They dressed it in elegant robes. They decorated it. They placed it in a chapel shrine. They duplicated it in the wood they carved out of trees. She became a favorite Madonna in western Mexico and northward into the United States. In many places throughout this great extent of territory she is skill a favorite Madonna. In some places her title has changed: In Chihuahua, Mexico, she is Our Lady of Chihuahua; in New Mexico, she is Our Lady of Santa Fe. The name has changed but the devotion and the statue are the same. Bishop Vasco de Quiroga was one of the geniuses of all time in the humane introduction of civilization among primitive peoples. His collaborator was Our Lady.

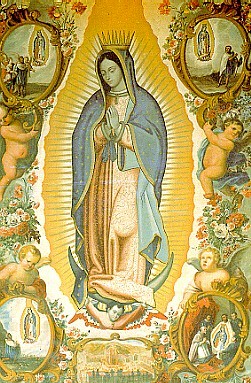

The second Madonna, Our Lady of Guadalupe, is Mexican in origin, and continental in the devotion she arouses. We choose her as the first of the native madonnas. Here Our Lady was pictured for the first time with the features of the new American, not Indian, but mestizo, the mixed race which would form the backbone of the new world in the Spanish plan of colonization. The story of the apparition of Our Lady to a Christian Indian, Juan Diego, in Tepeyac, in the environs of Mexico City, in 1531, is too well known to need retelling here. Suffice for us to recall that the picture as it is treasured today is the imprint which Our Lady herself left on the blanket of the Indian.

Tepeyac has been referred to as the Lourdes of America. The authenticity of the tradition, the age and pigments of the picture, etc. are details which do not concern us, but we may say in passing that here as in Lourdes the enemies of religion have tried in vain to prove that it is a fraud. The rapid spread of devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe was phenomenal. Everywhere the "little dark Virgin" became a favorite. Churches were built carrying her name; shrines, statues, medals all attesting to favors received through her intercession. Enterprises were undertaken in her name, as in Spain in the name of St. James. Penetration into our Southwest was under her patronage. The rallying cry of the Mexican War of Independence was "for Our Lady of Guadalupe" and her banners were carried by every regiment.

The popularity of Our Lady of Guadalupe is due to the tradition of the apparitions rather than to her Indo-Spanish cast of features. It is one of the notable facts of Marian devotion that native madonnas have never displaced the traditional European images. They exist side by side and there has never been any rivalry between them. Under whatever title or in whatever dress, Our Lady was the same queen, patroness, mediatrix to all Spanish, Indian, Mestizo, Negro. This coexistence of many particular devotions underscores how successfully the missionaries taught, and how truly Catholic, without sentimental attachment to any outward expression whatsoever, was the Marian devotion they instilled.

In the great stretches of our Southwest and Texas, which retained their Spanish-American affiliations until the middle of the last century, this colonial pattern of Marian devotion still obtains. In our Southeast, the Spanish Floridas which comprised our State of Florida and a considerable portion of the territory of other Southern states, the Spaniards were forced out earlier; the records of history are fewer and the characteristic features of their colonial culture have been erased. In spite of these circumstances, we must not undervalue Spanish accomplishment in this region. Estimates by historians for the early seventeenth century place the number of converts at twenty-five thousand, of mission settlements at forty-four and the number of Franciscans at thirty-five. All legislation by the Spanish Crown on ecclesiastical arrangements provided for the kingdom of las Floridas.

We have dwelt in detail on the Spanish chapters of our colonial history because the extent of the territory involved is so considerable a portion of our nation and because the influence of the Marian devotion of colonial days is still strong. We have a third motive in that the first two formal dedications of any national territory of ours to Mary the Mother of God came from the king of Spain. The first was issued by Philip IV in an edict addressed to his viceroys in America under date of May 10, 1643, which reads as follows:

"In recognition of the great mercy and many favors which we have received from the Blessed Virgin Mary, we place all our kingdoms in America under her patronage and protection, setting aside one day in each year in order that novenas may be begun in every city, town and hamlet. On each day of the novena Solemn High Mass is to be celebrated with greatest possible pomp and ceremony and a sermon preached. All officers of the Crown are to be present at the Mass in their official capacity at least on the opening day of the Novena. Processions are to be held everywhere and the statue or picture of the Blessed Virgin to which there is greatest devotion in the locality is to be carried processionally. ... We ask our Bishops to exhort the people to piety and devotion to Our Lady, our patroness and protector."

The second dedication, a renewal or extension of this one by Philip IV, was proclaimed not long before our Revolution, in 1760, by King Charles III. It was a specific dedication of our country as, "the Spanish borderlands," borderlands, we must bear in mind, which became part of the United States only in the comparatively recent era of the Mexican War.

We leave these "Spanish borderlands" to turn briefly to the influence of France on Marian devotion within the United States. In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, France challenged Spain's claim to the Mississippi Valley and then made good her own stake there, not by colonization, but by trading posts in which French and Indians lived together. From the point of view of the preaching of the Catholic religion and of devotion to the Mother of God, no one could have surpassed the French in missionary zeal. In Maine, along the St. Lawrence from Ville Marie, among the Hurons and the Iroquois, across the waterway of the Great Lakes establishing the mission post of Sault Ste. Marie down the Mississippi and west and east along its mighty tributaries, the French built their little chapels within the fortresses which they erected for protection and in order to hold the territory for their king. Hither they called the hunter, the fisher, even the fighter, to recite the Angelus, the Rosary, the Magnificat. The rivalry of England terminated the apostolate of the French after less than a century, but the love of Mary has remained wherever French influence has touched. As the Church under Bishop Carroll pushed westward and new dioceses assumed the ecclesiastical administration of the Middle West in the first half of the nineteenth century, the way of the immigrant and the pioneer was made less arduous by the vestiges of Catholicism in this once French possession. In the East the Catholic Indians of Maine balanced the British against the rebel cause, and made up their minds to espouse the Revolution only after the General Assembly of Massachusetts assured them that they would be provided with a priest. The devotion to the Blessed Virgin among French Canadians and Franco-Americans today attests how intimate and inseparable a part this devotion is of all French culture. In the national shrine to Our Lady in Three Rivers, Canada, the Society of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate offers an uninterrupted chain of Rosaries day and night throughout the year.

After the French missionaries going down from the North had met the Spanish missionaries in the South, only a little of what is now the United States remained to be conquered for Christ. That little lay within the mountain fastnesses in the northwest, and in God's good time missionaries would carry the Gospel and love of the Blessed Virgin there and beyond to Alaska, when that land should become a territory of the United States.

Meanwhile, in the East along the Atlantic seaboard the English were in undisputed possession, and the pendulum of history was about to swing in that direction. A new nation was soon to be cradled there. England had come to America in the first days of Protestant vigor when hatred and persecution of the Church were at their height.. Religious wars in Europe were scarcely over, politics was wearing a mask of religion and, in America, the two colonizing nations against which the English colonists must make their own advance were the Catholic nations of Spain and France. All the hostilities which were dividing Europe were operating against Catholicism here. Even in Maryland, the colony which owed its establishment to the experiment of allowing peoples of different religions to live and work together, the way of the Catholic was beset with great difficulties. Merry England Mary's England had come to America in Protestant robes, and the love of Mary which had once distinguished her had now been forgotten. Yet even in those years of Anglo-American colonial life the Mother of God was not without homage. It would be unthinkable that devotion to her did not exist in the homes of the Catholic gentlemen who set up the colony of Maryland, or that the Jesuits who stayed with that colony through thick and thin did not deepen the love of her in all whom they served or converted, or that the Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany in pre-Revolution days did not come with her scapular over their shoulders. The name of Mary was hushed to a whisper, but her help was still with us.

Then came the Revolution and a new nation dedicated to freedom. The Church, permitted legal corporate existence, became a factor in the life of the republic. At this point, as we have seen at the beginning of this article, Bishop Carroll dedicated his diocese, the then United States of America, to the Mother of Our Lord and Savior. With confidence in Mary's intercession, Bishop Carroll worked for a quarter of a century meeting problems of administration involving bishops and pastors, problems of assimilation and immigration, of a still smoldering anti-Catholicism, problems of the growth of the Church and of the establishment of institutional life. Precedents were lacking. Bishop Carroll and his associates had to create new patterns to meet all problems, age old or brand new. The story of those trying years, so memorable a page of our history, is not the subject of these pages. Enough to know that soon the Church began to flourish and to give promise of the bright future that was in store.

As immigration increased, administration of the Church from distant Baltimore became less and less practical and new dioceses were erected. No new declaration of Mary's patronage was necessary since all the new dioceses, as previously part of Baltimore, had already been given into the care of the Mother of God. The new dioceses progressed amazingly. By the middle of the nineteenth century the number of Catholics in the United States had mounted to about a million and a half, the number of dioceses to more than a score. Priests, many of them from Europe but augmented by a rapidly growing American clergy, were making it possible to build parishes to meet the needs of the people.

These were the years when the discussion about the Immaculate Conception was arousing the interest of Catholics all over the world. The young Church in America, already dedicated to Mary, petitioned as an act of public veneration of the Immaculate Conception, to have the title of its patronage changed to Mary Immaculate.

Archbishop Samuel Eccleston of Baltimore called the Sixth Provincial Council of the Church in America in 1846. Twenty-two bishops responded, and the Council passed as its first decree the resolution to choose Mary Immaculate as the Patroness of the United States and to make December 8 the patronal feast. In the Pastoral Letter issued by the Council, dated May 5, 1846, we read:

"We take this occasion, brethren, to communicate to you the determination, unanimously adopted by us, to place ourselves and all entrusted to our charge throughout the United States, under the special patronage of the holy Mother of God, whose Immaculate Conception is venerated by the piety of the faithful throughout the Catholic Church. By the aid of her prayers, we entertain the confident hope that we will be strengthened to perform the arduous duties of our ministry, and that you will be enabled to practice the sublime virtues, of which her life presents the most perfect example."

The following year the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide sent its announcement that "our Holy Father Pius IX most willingly confirmed the wishes of the Council that has selected the Blessed Virgin, conceived without sin, as the patroness of the Church in the United States of America."

This was in 1847 and the dogma was not defined until 1854. The Seventh Provincial Council in 1849 petitioned the Holy See for the definition of the dogma and called upon all the faithful to offer daily prayer that the Holy Father would hasten the pronouncement. When it came on December 8, 1854, every church in the country held services of thanksgiving. The Eighth Provincial Council, in 1855, gave official expression to the rejoicing of the people. Eleven years later, 1866, the second Council decreed that December 8 be observed in every diocese as a holy day of obligation.

The crown of Mary as Patroness of the Church in the United States was now all but complete. It had been shaped by Spanish pioneers, jeweled by the blood of missionaries of Catholic nations of Europe, carried in loving hands by Indian neophytes. Hard pressed colonists had hidden it away for a night, but when dawn came it was placed on one shrine after another as they increased and multiplied with the rapidly growing Catholic population. A priest who wrote in 1866 counted hundreds of churches dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. Today there must be tens of thousands of churches and chapels bearing her name and titles. In my own Archdiocese there are eighty-six parishes and ninety-one institutions dedicated to her, and thirty religious orders working in her name and pledged to her service; also as in every diocese, Sodalities, Rosary Societies, Legions of Marv, Holy Family Associations, vocation groups, Catholic Youth Organizations...everywhere "Hail Mary, full of grace ... pray for us now and at the hour of our death."

If we do not go into detail on the growth of Marian devotion in recent years, the reason is not to be found in any embarrassment of riches. It is clear that to the Catholics who emigrated from Europe, many of them to escape religious persecution, the love of Mary was their priceless inheritance. As the gates opened wide they came from Ireland with Our Lady of Knock, from Poland and Lithuania with Czestochowa and Ostrobrama, from Portugal and the fishing banks of the Azores with Our Lady of Good Voyage. Devotion to the Blessed Virgin was a lingua franca to these many Catholics of different national origins. It was also a bond which brought them all together as devotion to Our Lady under the titles of her recent apparitions notably of the Miraculous Medal and of Fatima became popular. Outdoor May processions, pilgrimages to local and diocesan shrines, the almost constant recital of the Rosary on one radio station or another, stadium gatherings of tens of thousands to witness a "Living Rosary" and to recite the beloved chaplet in mighty unison, the use of television to record these events, garden shrines, becoming so frequent as to rival the ancient wayside shrines of Catholic countries all give proof of the ubiquity and intensity of Marian devotion throughout our country. Mary was with our land when aboriginal peoples were being taught her name; she is with us now when our nation has developed into world hegemony. May she obtain for our leaders the wisdom necessary to withstand the forces of evil which are drawn up against us.

To complete the crown of Mary Immaculate as Patroness of the United States there remained the building of a national shrine which should serve as an outward expression of our love and as a place of pilgrimage where honor should be paid to the Mother of God who had protected our nation in all its days. At the time of the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, 1904, a national shrine to be built in Washington, on the grounds of the Catholic University of America, began to be speculated upon by members of the hierarchy of our country. Plans were laid, and ten years later His Holiness Pope Pius X, sent to His Eminence, James Cardinal Gibbons, the blessing of the Holy See upon the project. World War I intervened. In 1920 Archbishop Bonzano, the Apostolic Delegate to the United States, celebrated Mass outdoors on the site. Within a few months Cardinal Gibbons laid the cornerstone with solemn ceremonies, attended by a large number of the hierarchy and by diplomatic representatives of twenty-four nations.

The shrine itself, as planned, is 465 feet long and 238 feet across the transepts. The crypt, approximately half the area of the projected structure, was begun. The beauty of the crypt has been described at length by several writers. It is, in general opinion, the world's most beautiful crypt, with the sole exception of the new excavations in the Vatican. The marbles and mosaics beggar description. Fifty-eight nations are represented in the columns, each with reference to a leading shrine in the country. Throughout the plan of decoration in stone and mosaic and painting, the whole theology of the Church's belief in regard to the Blessed Virgin can be read. The main altar, a solid block of golden onyx resting on Traventine marble, is called the Mary altar, the gift of those of our land whose name is Mary.

It is not the moment to go further into the description of this extraordinarily beautiful crypt, for the Romanesque basilicas is now rising to completion. The campanile, 332 feet high, has been raised; the doorways, with their moving inscriptions, set; the walls climbing higher and higher to the mighty dome. Only the magnificent interior is of the future.

The National Shrine will attract even those who know the great basilicas of Europe, because of its majesty and beauty. In a country now accustomed to architecture on a grand scale, Mary's shrine is second to none among our most imposing structures. It is the gift to Mary of the people. Altars, windows, etc., may be individual gifts, but the over-all cost has been met by the collections throughout the country. In it is symbolized the solemn beauty of every adobe hut and log cabin which once echoed to the rhythmic recitation of the Rosary, every humble church built by the pennies of immigrant children of Mary, every convent and monastery wherein her Magnificat has been chanted in the Office of the day, every parish church across the land which bears her name, every church or chapel, home or garden walk where her statue stands or picture hangs, or praises are raised unto her heavenly throne. Love burns there, the love of millions upon millions. Faith is tabernacle there, the faith of those who know the Redemption. Hope lives there, the hope of our immigrants seeking freedom of worship, the hope of all of us in God's promise of eternal bliss.

Mary Immaculate, Patroness of America since America was a name, we salute you and beg your blessing on our land now and in the dim troubled eras of the future.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.