Catechism and Mary

Mary—A Living Catechism

Catechism and Mary

– Father Johann G. Roten, SM

Catechism and catechisms suggest synthesis, a synthesis of our faith. The word synthesis stands for unity and totality. Our faith is not a bag of mixed goods, haphazardly picked from various trees of knowledge. The catechism, whatever its precise historical expression, is first and foremost the testament of one person and his work, Jesus Christ. Jesus is the foundation of the catechism's unity and totality. Here lies the reason why Christianity will never be reduced to a simple religion of the book. However, many the editions of the Church's book of precepts and beliefs, it will always fall short of God's revelation in the fullness of time which we call Jesus Christ.

Book and Person

There are many reasons why there will always exist a chasm, notional and existential, between book and person, between the Catechism of the Catholic Church and the person and work of Jesus Christ. The human person is gifted with individuality, a human characteristic termed by tradition as "mystery." The human person is a mystery for him/herself and for others. There is a depth in each man or woman that escapes our grasp. Each one of us will always be more than "what we know and understand" about who we are and what we are to become.

To be mystery points to two seemingly opposed but, in fact, complementary realities: we are limited, on the one hand, by the fact that we are individuals and yet are created by God. Thus the source of our very being is out of our reach. On the other hand, however, our being is so close to the source of all being that we can almost touch it. Indeed, God is at hand provided we recognize ourselves being from his being, t。ruth of his truth, and life of the source of all life. No person is an island, basically because there is no way we can detach ourselves and drift away from the all encompassing divine continent.

Jesus Christ, being truly human, participates in human "mystery." He escapes our grasp not only as God-man but also as man. No sonar system will ever be able to penetrate the depth and width of his human soul, and the intimacy of his thoughts and feelings. The same applies to his divinity. We know of Christ's intimate relationship with his Father in heaven and of some of the wonderful events and deeds of his life. But how could we ever adequately imagine, much less understand, the true nature and love and "might of God among us who is one of the Trinity."

As human and as Son of God, Jesus Christ cannot be contained in all of the catechisms written about him and will always be bigger than the biggest and most comprehensive catechisms about him, that is about his person, what he said and what he did. "A person can be understood by another person only through ways proper to human interaction, communication, and encounter." This is true of our relationship with Jesus Christ. No dogma or institution will ever exhaust or replace the intimacy of Christ's encounter with the soul. Christianity stands and falls with the intimate certainty – more intimate than any other personal and acquired certainty of the human order – that God's revelation in Jesus Christ has immediate significance for me and each one of us.

"Still, these are not reasons enough to cherish less our catechism. On the contrary, God's overwhelming love for us needs all the warranty and protection it can get. The catechism is such a warranty and protection. It is a sign of our poverty and God's grandeur. We need to be constantly reminded that God will never forego his pledge of allegiance to us. And God in his loving grandeur is humble enough to recognize this need of ours, born of our limited condition and weak faith.

Mary as Model for All Catechisms

"Mary's place in the catechism is important, first and foremost because she is and has been the privileged person and partner of God's revelation in Jesus Christ, and is thus a permanent model and key for all catechisms." Mary is the one who helps us unravel divine revelation about the person of her Son Jesus. God did not speak into the void or into empty space. His word was meant for a human addressee in expectation of a positive answer. Thus, Jesus and Mary constitute the original dialogical situation upon which the catechism is grounded. Mary is the first and perfect example of the "person whom grace has transformed into a new creature." This person begins to follow Christ – says Catechesi Tradendae (#20) – and in the Church learns daily how "better to think like Christ, judge like him, act as his commandments require, and in whom he bids us to hope" (ibid.). It does not come as a surprise that Mary is regarded as teacher, she, who was the first disciple of Jesus ... "the first in rank, for no one became so profoundly docile to God as she" (Cat. Trad., #73). Not enough to identify Mary as disciple and teacher, the Pope sees in her person a "living catechism" and "the mother and model of catechists." But John Paul II is by no means the first and only theologian to highlight Mary's teaching role in the Church. To be a teacher is one of the classical attributes of Mary, recognized as such by no less a Marian critic than Luther himself: "Mary teaches us – he says – to know the gifts that God gave us."

From Profession of Faith to Compendium of Doctrine

The understanding and form of the Christian catechism varies in time. The history of teaching about Jesus Christ begins as a story, the so-called salvation history approach or kerygma as found, for example, in Saint Stephen's profession of faith, the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, or the mystagogical homilies of Cyril of Jerusalem, Ambrose and John Chrysostom. The meaning of kerygma is to witness by proclamation and profession. One proclaims a truth and simultaneously professes a religious experience. Truth and experience are the two pillars of salvation history since they translate for us the human expression of divine revelation. In proclaiming the truth of God, we point to his mystery, the infinite and inexhaustible reality of his power and grace, a truth, therefore, which leads ever deeper into the recesses of divine overabundance. God's truth is not proclaimed in a detached and abstract manner, but as something that has touched, enlightened and transformed the minds and hearts of believers. Proclamation becomes profession, making the one who professes a living and visible, as well as active, witness of God's goodness. Here lies the beginning and meaning of the term and notion of sacrament. God's truth will be truly such only when and if it becomes concrete expression in human reality. "Therefore, it is accurate to say that the two expressions, mystery and sacrament, are key concepts of any Christian catechism." Manifestation and presence of God in this world summarizes much of what Christian doctrine and piety is all about.

Not all catechisms follow this basic pattern. In time, the initial kerygma, i.e. baptismal and liturgical faith professions, evolved toward more systematic and less existential presentations, take for example, Gregory of Nyssa's Great Catechism or Augustine's Collection (on faith, hope and charity) containing the baptismal creed, the Lord's prayer and the two great commandments. These latter elements increasingly determined the catechetical digests of the Middle Ages. In the Minimal Norms (1000-1200) little attention is given to creation and salvation history, the focus centers on moral teaching and the practical aspects of prayer. The Catechism as we know it today lived its heyday during the Post-Reformation period. Protestants (Heidelberg Katechismus, 1563) as well as Catholics (Catechismus Romanus, 1566) produced their respective faith manifestos, large and small, based on a question-and-answer approach, and marked by a strong intellectual slant. In subsequent centuries (1650-1850), this monolithic and uniform concept gives way to a certain pluralism. It gives rise, for example, to catechisms for specific audiences: rural (Jean Eudes, Vincent de Paul), urban (St. Sulpice, St. Nicolas du Chardonnet) and ethnic catechisms (for example, the English Penny Catechism or Fleury's historical catechism in France).

After Vatican I a new form of pluralism, albeit in strict conformity with the Roman catechism of Trent, developed. The results were national catechisms for use in schools, etc. and based on a three-part outline covering truths, duties and means (see for example the Baltimore Catechism, 1885; Pius X's Compendio della dotttrina cristiana, 1912, and, for France, the Amette Catechism of 1914). The universal catechism, called for by the First Vatican Council, never saw the light of day. During the decade before Vatican II some attempts were made to create innovative catechisms by integrating kerygmatic theology, the Church's liturgical life, and principles of modern pedagogy, for example, the Katholischer Katechismus for family use (Germany 1955). The period after Vatican II, which mandated the creation of a general directory (1971), saw the publication of some controversial catechisms leading ultimately to the creation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church officially promulgated on December 8, 1992. Among the so-called controversial catechisms we have, for example, the Dutch Catechism (1966), Vamios caminando (Perce), and Christ Among Us (USA). Accepting change and pluralism as positive values, these catechisms emphasized individual theories and contemporary theologies over and against traditional Church teachings.

Doctrine for Life

In summary, the CCC (Catechism of the Catholic Church) was to be an official Church answer to a number of grave questions, namely, how can we root pluralism in unity, retrieve the tradition of the Catechism while integrating the teaching of Vatican II, and simultaneously proclaim a message of true liberation for everybody (CCC 2864). The CCC is the organic and complete presentation of the fundamentals of Catholic doctrine dealing with faith and morals based on Vatican II and the whole of Church tradition. It was not planned as a handbook for everybody, but rather as universal point of reference for regional and local adaptations by bishops and bishops conferences throughout the Catholic Church. Composed of 2865 articles, the CCC departs from the traditional question-and-answer schema to follow a methodological sequence of (1) exposition – (2) commentary – (3) illustration and (4) summary. Originally formulated in French, the CCC is not based on the teaching of contemporary theologians but on Scripture, the fathers, councils, popes, saints, and especially Vatican II. In his document presenting the CCC, John Paul II turned to Mary (Blessed Virgin, Mother of the Incarnate Word and Mother of the Church) asking her to sustain and support through her powerful intercession the catechetical task of the Church engaged in new frontiers of evangelization. In doing so, he called her light of truth and faith, and presented her as the one who liberates humanity from ignorance and the slavery of sin so as to lead it to true freedom.

The universal catechism takes its basic structure from the Roman Catechism and its presentation is in four parts: symbol, sacraments, commandments and prayer (Our Father). Contrary to Augustine's A summary or Collection Concerning Faith, Hope, and Charity and St. Thomas' Neapolitan Catechism who centered their catechetical teaching around the symbol (Creed), commandments and sacraments (presentation in three parts), the CCC clusters its four-part approach on the Profession of Faith (art. 1-1065), the Celebration of the Christian Mystery (1066-1690), Life in Christ (1691-2557) and Christian Prayer (2558-2865). Each of the four parts offers a general or educational section followed by specific and practical aspects; so, for example, in its second part (Celebration of the Christian Mystery), is a development on sacramental economy, its understanding and meaning leading into the presentation of the seven sacraments. Although scattered over all four parts of the Catechism, the Marian texts or references (roughly eighty mentions of which fifty-nine belong to major texts and the remaining ones to so-called minor texts) are found mainly in the first and fourth part of the CCC. None of these texts represents a synthesis of mariology, but the texts on Mary in this catechism are more numerous than in any other catechism of the past.

Theological Characteristics

The CCC presents a number of general theological characteristics which help to situate this document with regard to other, previous catechisms. The following list gives a first overview of these characteristics. The CCC is

Theocentric > more than anthropocentric

Sacramental > historical

Kerygmatic > notional

Spiritual/liturgical > theological/doctrinal

Organic > hierarchical

The descending movement of God's revelation has priority. God's unending self- communication precedes human transcendence, and culminates in the celebration of the mighty works of God (Magnalia Dei). This means the continuity of God's presence (past, present and future) and its witness (proclamation and profession) takes precedence over descriptions of the Church's historical evolution and discursive assessments of her truths. In the same vein, personal faith and adherence are more highly regarded than theological speculation and the quest for assent. The whole is structured according to the principle of the "connections between the mysteries of faith" (nexus mysteriorum) favoring harmony, synthesis and interconnection among the various truths of Christianity rather than their differences, degrees of certitude and subordination. The CCC has a strong spiritual and existential note, giving ample space to the experience of saints and mystics through the ages. Being the first and foremost saint of the Christian religion, Mary's place in the catechism is enhanced, in contrast with the importance given to her in previous documents. While strongly accentuating her divine maternity and virginity, older catechisms (Canisius, 1555; Romanus, 1566; Deharbe, 1847) mentioned Mary's role with regard to salvation and the Church only peripherally or omitted it altogether. She was greeted as Virginal Mother and invoked as mother of mercy (Canisius), powerful queen (Romanus) and intercessor in the hour of death (Deharbe). Among the Marian prayers taught regularly through the ages we find the Hail Mary, the Angelus and the Salve Regina.

The Marian Texts

As mentioned, the CCC devoted to Mary a series of major key texts dealing with her relation to the Trinity, Jesus Christ, and the Church. Others to be considered as major texts are: the prayer of Mary (2617-2619) and prayer in communion with the Holy Mother of God (2673-2679). The first three texts form part of the profession of faith (Section I of the CCC); texts four and five belong to Section IV dealing with Christian prayer.

1) Christ-centered texts (art. 422-512)

Not all of these articles speak about Mary. However, the catechism points out with emphasis how much and intimately Jesus Christ, the "only Son of God" is linked in his humanity to the woman Mary. We distinguish four major affirmations and/or developments: the foundational statement of Gal. 4,4 (born of a woman) (422); the Jewishness of Jesus, born a Jew of a maid of Israel (423); the importance of Mary's virginity and motherhood (Theotokos) in the christological debate leading up to the doctrinal statements about Jesus Christ "true God and true Man" (471- 483): Ephesus (431): true Mother of God "according to the flesh"; Chalcedon (451): "born of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God (Theotokos), according to his humanity"; Constantinople V (553) which states that one of the Trinity who "deigned for our salvation to be incarnate of the Saint Mother of God, and ever Virgin." These developments can be summarized in a contemporary formulation borrowed from Gaudium et Spes: "Born of the Virgin Mary, he truly became one of us, in everything like us, except sin" (GS 22,2).

The fourth and most ample development deals with the agents and events of Christ's incarnation: conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary (484-512). The content of these articles comes closest to what the CCC has to offer in terms of a comprehensive portrait of Mary or a Mariological mini-treatise. Combining scripture and tradition, salvation history and dogmas, the catechism presents successively some of the major articulations of the theological discourse on Mary: her having been chosen by God, Immaculate Conception, the Annunciation (Fiat), Divine Motherhood and virginity (ever virgin). The major theme of this section, the virginal maternity of Mary, is reassumed in articles 502-507, only to be situated in the broader context of revelation in its totality.

2) Spirit-centered texts (art. 721-726)

The progressive emergence of the Spirit in salvation history evolves from a time of promise (creation, theophanies, advent of the Messiah) to the manifestation of the Spirit of Christ in the fullness of time, and the joint mission of Son and Spirit. It is in this particular context that the catechism deals with the relationship between Mary and the Holy Spirit: Mary is the masterpiece of the joint mission of Spirit and Son; she is the dwelling place or temple of Son and Spirit offered to the Father, and is thus understood as Seat of Wisdom. She deserves this title because it is in and through her person that the marvelous deeds of God become manifest through the Spirit. The action of the Spirit in Mary is progressive: He prepares her by his grace, accomplishes in her the plan of God, and manifests the Son of the Father as the Son of the Virgin. In Mary, the Spirit established the communion between Jesus Christ and representatives of humanity in need of redemption; in him, she becomes Woman, New Eve, meaning "mother of the living, and mother of the "total Christ."

3) Church-centered texts (art. 963-975)

The Church, in the plan of God, its origin, foundation and mission in Christ, not only is marked by the stamp of its founder but also finds a model in her who was its original and super- eminent member. Indeed, Mary precedes us all in sanctity. She is the "spouse without stain nor wrinkle" (Eph. 5,27). Because of this, "the Marian dimension of the Church precedes the petrine dimension" (MD 27).

The catechism devotes Section VI of its development on the Church to Mary, Mother of Christ, Mother of the Church, thereby closely following the teaching of Chapter VIII of Lumen Gentium. In her we contemplate not only the true Mother of God, our Redeemer, but also the Mother of the Members of Christ and Mother of the Church. Mary's maternity of and for the Church comprises a variety of facts grounded firmly in her relationship and cooperation with Christ: She is totally united to her Son in her life and in her Assumption, and thus becomes our mother in the order of grace. She is, in the practical order of Christian life, a model of faith and of charity, and so constitutes its exemplary realization. Mary's maternity in the economy of salvation endures until consummation. Contemplating in Mary the mystery of the Church, the CCC identifies her as its eschatological icon. Mary is a sign of hope and consolation for the pilgrim church; she inaugurates and warrants in the here and now the ultimate achievement of the heavenly church.

Given the importance of Mary for the self-understanding and realization of the Church, cult or devotion of the Holy Virgin is considered an integral part of Christian worship. This legitimate and special devotion goes back to the earliest times of the Church when the Virgin Mary was honored as Mother of God, refuge and protection against danger, adversity, and in needs. However, Marian devotion is essentially different from (and in the service of) the cult of adoration devoted to Father, Son and Spirit (LG 66). It finds a twofold expression in the liturgical celebration dedicated to the Mother of God (SC 103), and in Marian prayer; for example, the rosary, sometimes called the "summary of the Gospel." (MC 42) The biblical foundation of Marian devotion is to be seen in the passage of Luke, "All generations will call me blessed" (Lk 1,43).

4) Texts centering on Mary's prayer (art. 2617-2619)

This short but highly meaningful paragraph stresses the archetypal function of Mary's own life of prayer. It echoes the example of Christ who prays, teaches us how to pray, listens and acts on behalf of our prayer. Similarly, the prayer of Mary reveals three things: (1) It is presented to us at the Annunciation and Pentecost as unique cooperation in God's plan; (2) At Cana and Calvary we are led to discover Mary's prayer of intercession in faith; (3) Above all it is Mary's Magnificat which shows what hope fulfilled means, for the Mother of God as well as for the Church.

5) Texts about praying in communion with Mary (art. 2673-2679)

Among the various "ways of prayer" mentioned in the CCC there is not only prayer to the Father, to Jesus and with the Spirit but also encouragement to pray in communion with the Holy Mother of God. 'One who points the way', 'One who prays', 'Sign' – Mary is perfectly transparent to Jesus who is our way in prayer as in everything else. (1) Mary is the Hodegetria, meaning the "One who points towards (Jesus)" used to classify icons of Mary: She points the way to Jesus who is the way of our prayer. Much of what we call spiritual maternity takes its origin and meaning here. She is (2) the sign, meaning she is all transparence unto Jesus, our model of speaking to his and our Father.

Centered on Christ's person as manifested in his mysteries, our Marian prayer follows a double movement as described in the Hail Mary and Holy Mary (1) It is praise for the great things the Lord accomplishes in and for his humble servant (=Hail Mary); (2) it signifies entrusting to Mary all supplication and needs of God's children (=Holy Mary). Thus Mary, the perfect Orans (The one praying or at prayer), becomes a figure of the Church: She assents to God's plan. As members of the Church, we invite Mary into "our being," praying with her and praying to her, for Mary's prayer sustains and supports the prayer of the Church.

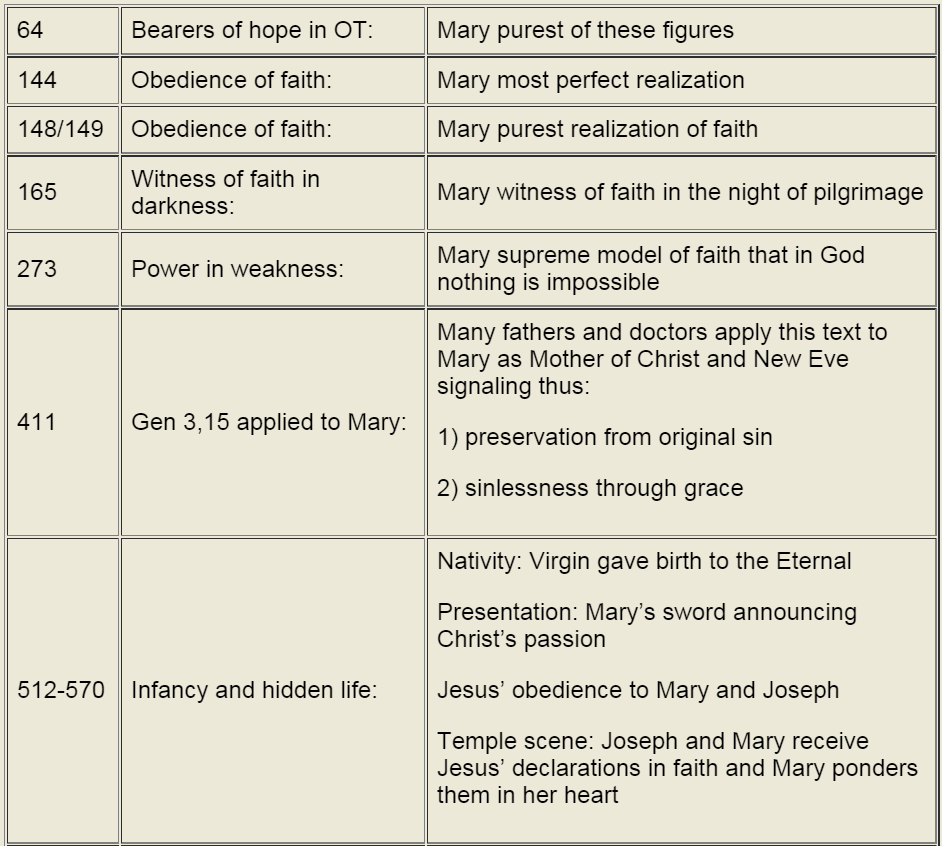

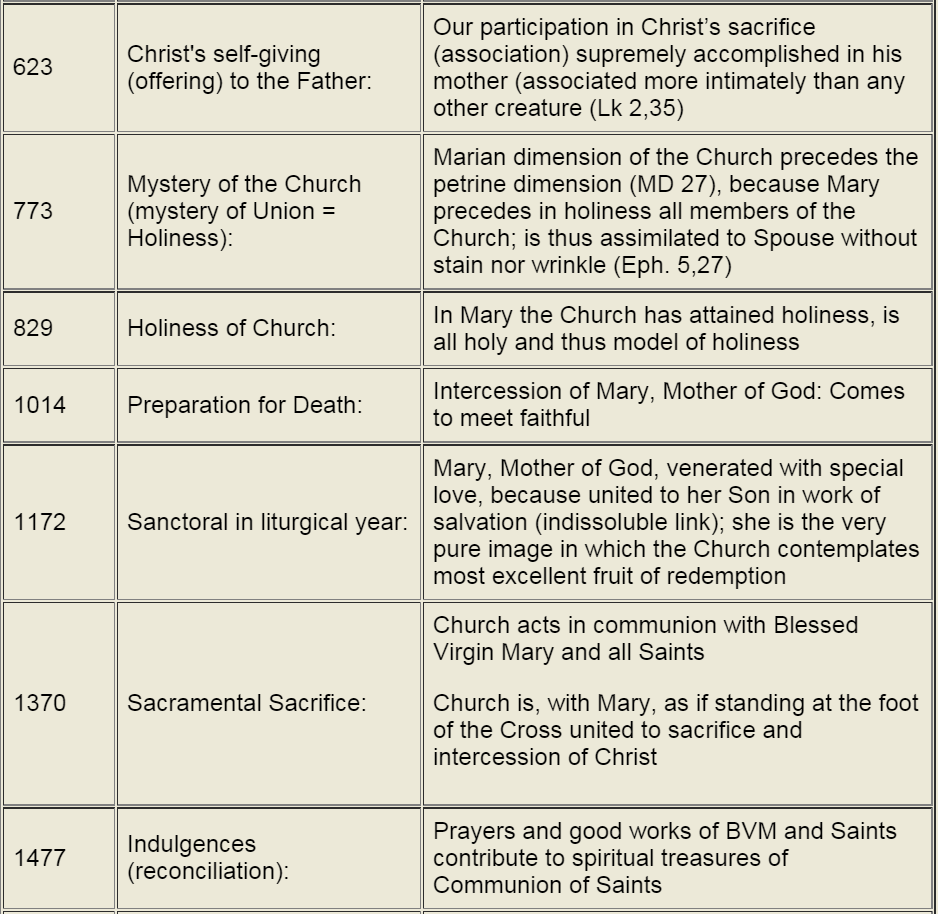

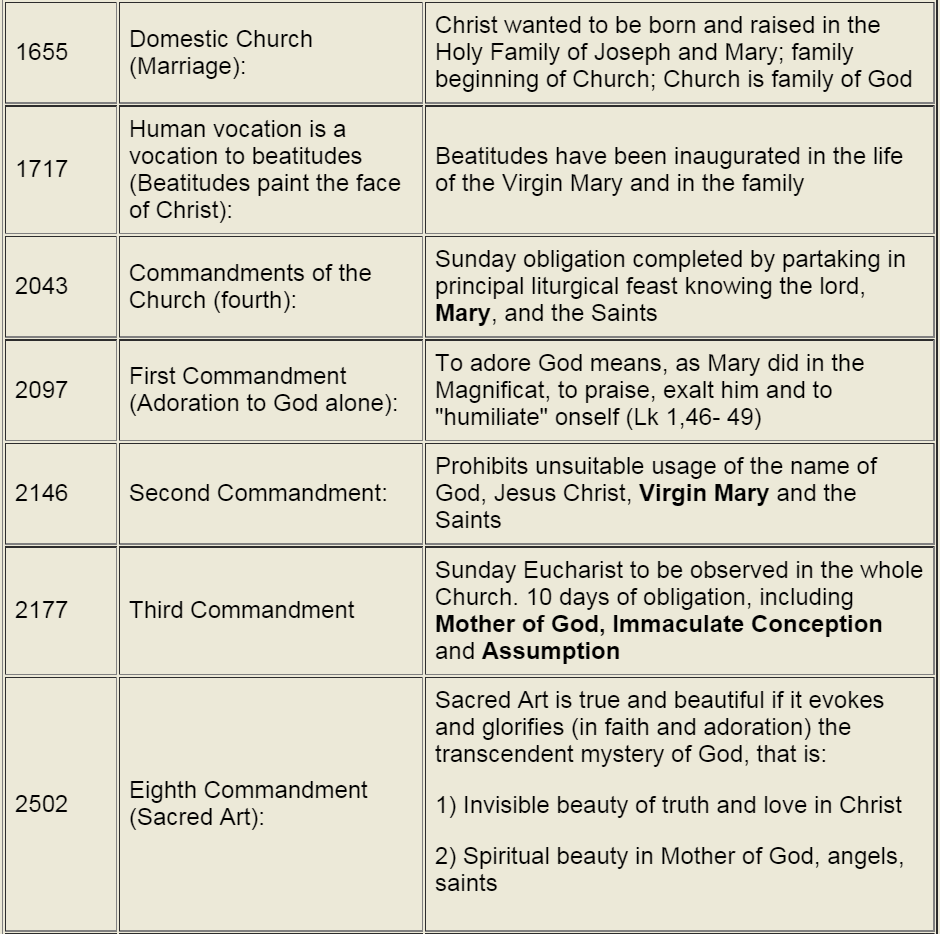

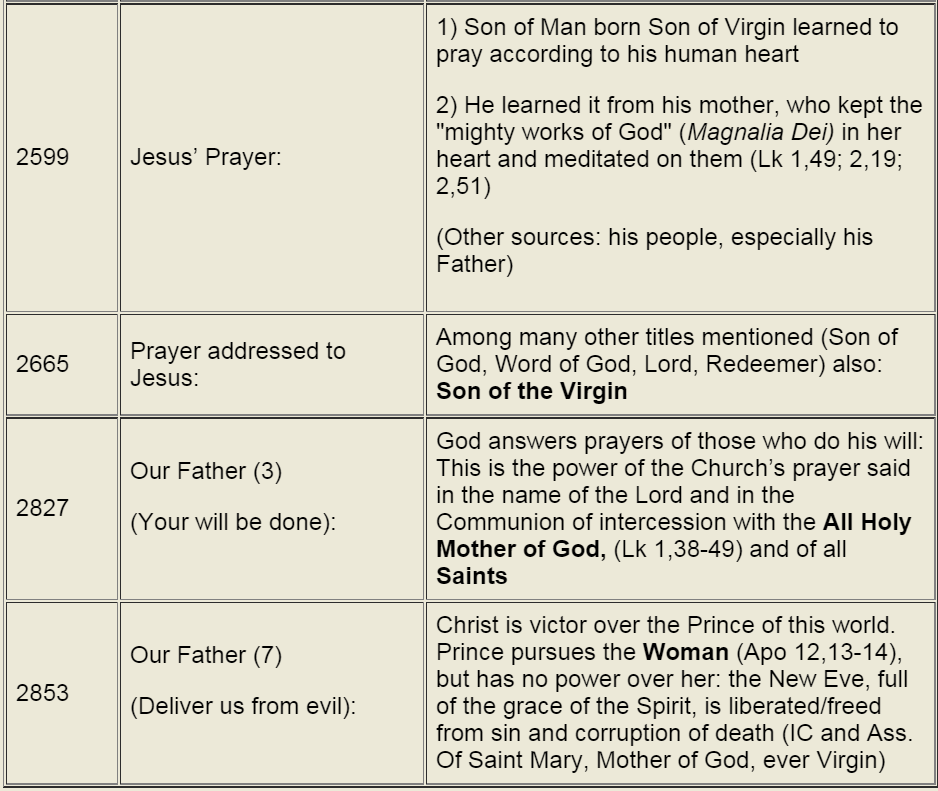

These are the texts which constitute small but significant syntheses on or regarding important points of revelation related to Mary and flanked by a relatively high number of more disparate elements of information about Mary (twenty-five total). We would like to give an overview of these elements with the following chart:

In this overview the numbers refer to articles in the CCC, the descriptive elements in the second column highlight the thematic context where the statements about Mary (third column) can be found. The variety of information (from preparation for death to sacred art) shows the wide range of the catechism's Marian interests. We find in Mary not only a description of who we are as Christians (for example, "purest realization of faith," art. 148/149) but also a helper and model (for example, "she comes to meet the faithful," art. 1014). Most important, Mary as another self and as eschatological icon of the Church warrants presence and encompassing motherliness to all the faithful until the end of time and trial.

The Marian Profile

The question may be raised as to whether the presentation of Mary in the CCC corresponds to and reflects the underlying theological principles used in the construction of the text. The catechism is built around three theological realities: mystery, economy and sacrament. The mystery of the Trinity reveals itself as presence of inexhaustible love. We call this revelation: economy to signify the active character of this presence as manifested, for example, in Jesus Christ. The active loving presence of God has a permanent character and is of sacramental nature. It is concretized in the Church – sacrament of Jesus Christ – and its other sacraments. If mystery is reflected foremost in the Spirit as pure expression of love, then the economy of salvation is embodied in Jesus Christ and its sacramentality in the Church and its works. Mary, as virgin and mother, in some ways reflects these theological realities of mystery, economy and sacrament:

(1) As masterpiece of the Holy Spirit, she is the human reality which makes God's presence possible without resisting or demeaning it. Her name is transparence, her vocation holiness. She is the faithful conductor of God's mystery, and inaugurates human vocation as a vocation to the Beatitudes. Sinless, predestined, immaculate: these various descriptions of Mary's identity point to the work of the Holy Spirit within her.

(2) Mary's holiness is not self-contained. It has functional or practical significance. She is involved in the progressive realization of God's plan. She becomes an active part and agent of the trinitarian economy through her virginal maternity. Mother of the Incarnation through her Fait, she is drawn by her Son into a unique cooperation in his salvific work as mother, disciple and associate. This role culminates in her permanent vocation as the woman or mother of the total Christ.

(3) In the sacramental order of salvation Mary's prominent role is that of being a model of the Church. As mentioned previously, the sacramental order reflects the continuous and active loving presence of God in this world. The Church assumes this role, but it is in Mary that she finds her most perfect realization. The CCC is full of references in this regard: Mary is not only in generic and practical ways the Mother of the Church. She is model of prayer, sign of eschatological hope, seat of the Church's wisdom, sign of transparence unto Jesus, supreme model of faith, and, of course, supreme accomplishment of our participation in Christ. Without being a super-sacrament of the Church, Mary is nonetheless a benchmark or litmus test of the true sacramentality of the Church. In conclusion, the CCC allows us to contemplate Mary not only in bits and pieces, determined by functional or utilitarian criteria, but also as compact and comprehensive figure whose identity, role and model character are fashioned and made explicit, thanks to the theological foundations of mystery, economy and sacramentality.

Weaknesses and Novelties

All of this does not mean that no criticism should or could be voiced regarding the presentation of Mary in the CCC. The analysis and description of her faith, otherwise so highly praised, is omitted (art. 199ff.); she is not presented as teacher of our faith (art. 166-175). Mary is not explicitly mentioned as theological focal point of the Trinity at the moment of the Annunciation (art. 238-248). The presentation of Mary's role as mother is static, and does not take into consideration her role as educator in the human development of Jesus, her Son (art. 471-488). The development of the mysteries of the life of Jesus (art. 570) does not mention the rejections of Mary and the event of Cana. In the description of Jesus' resurrected humanity, no mention is made about Mary's assumption, that is her own resurrected humanity (art. 631-658). Mary is not addressed as sister; neither marriage nor virginity for the Kingdom say anything about Mary's role (art. 1618). The human vocation as image of God foregoes the opportunity to refer to Mary as principal model of God's image and likeness in humanity.

However, the possible omissions mentioned here should not demean or devaluate the overall positive assessment. We are presented with a Marian teaching that is both rich and sober. Mary is pictured as a strictly religious figure, foregoing easy psychologization and historization. Mary's cooperation in Christ's salvific work is not qualified beyond her role as mother and intercessor (there is no mention of her coredemption). Mary's privileges have essentially functional character; little or no moralizing or apologetic interpretation of the Marian dogmas is attempted, except perhaps for the explanations given for Mary ever-virgin.

In sum, the mariology of the CCC is a faithful reflection of Lumen Gentium, Chapter 8. Among the riches and novelties of the catechism we count especially the development on the relationship between Mary and the Holy Spirit. In exploring the relation between the Holy Spirit and Mary, the CCC strikes out into new territory and compensates for some of the omissions of the conciliar mariology. Other points to be highlighted are the positive formulation of the Immaculate Conception seen as holiness, the nature and number of practical spiritual applications, the constant preoccupation with pointing out Mary's relatedness to Church, Christ, Trinity and each one of us, and – last but not least – the marked model character of Mary's life in faith and charity (for example, she is the purest, most perfect, most accomplished point of reference among God's creatures).

A Living Catechism

In general, the CCC's mariology is that of Paul VI rather than that of John Paul II. The Marian discourse is expository, descriptive, esthetic, typological and ecclesiotypical. It does not take into consideration John Paul II's 'personalism' as expressed in Redemptoris Mater and Mulieris Dignitatem. Faithful to Vatican II, the catechism does not discuss and adopt contemporary currents in mariology such as those influenced by liberation theology, feminism, psychological interpretations, apparitions, cultural diversity, and specific spiritual movements and values (for example, de Montfort consecration). The profile of Mary is clustered around holiness, a central aspect of theological anthropology, but does not refer to other dimensions of the human person (dignity, justice, human development). The image of Mary, in tune with the overall thrust of the catechism, is deeply spiritual, and its presentation strongly symbolic. This is due principally to the foundational principles of mystery and economy and sacrament, to the highly relational and representational character of the person of Mary, not least to the influence of the Orthodox tradition. For these and other reasons, the presentation of Mary in the CCC can rightfully be claimed as a summary of the Gospel, and Mary herself as a living catechism. She deserves this description because of her Fiat which is essentially the correct answer to the situation preceding it, and making the Fiat possible. Indeed, Fiat means to be completely God's, since, first and fundamentally, he has been ours. This is what makes Mary to be a living catechism.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.