Black Madonnas: Origin, History, Controversy

Black Madonnas: Origin, History, Controversy

– Michael Duricy

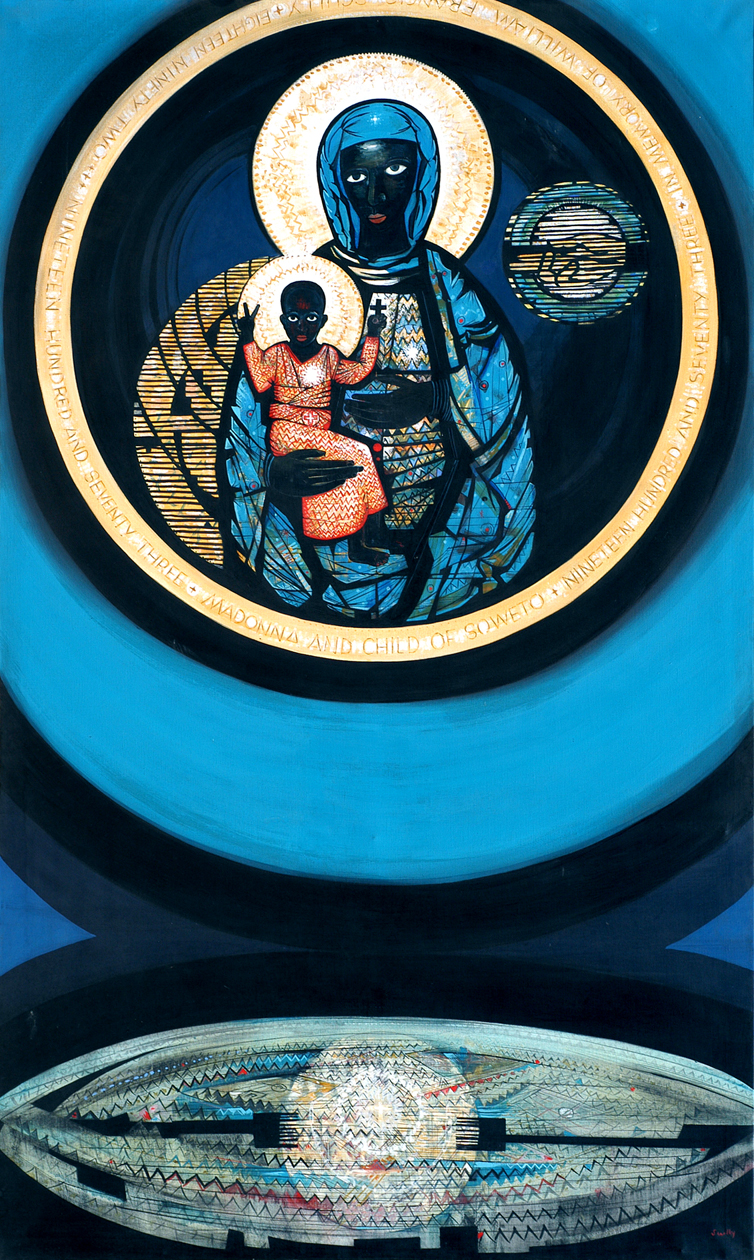

There are black Madonnas and Black Madonnas. The former applies generically to any dark-skin-colored representation of Mary. Falling into this category are recent depictions of Our Lady like Larry Scully's Madonna and Child of Soweto. The term used frequently to designate these images is inculturated Madonnas, meaning artwork by African or African-American artists (sometimes also by artists of a different racial background) for people of the same or similar cultures. These representations may convey a critical message inasmuch as they highlight the universal and thus trans-racial significance of the Christ event (including Mary). Most of these images are of recent origin; others came to prominence only recently. In the latter case we are dealing with sometimes century-old artwork of Africa whose artistic and spiritual values have been ignored for a long time.

Madonna and Child of Soweto, Larry Scully

Madonna and Child of Soweto, Larry Scully

However, this is not the topic of the following feature. The meaning of Black Madonna used here refers to a type of Marian statue or painting of mainly medieval origin (12C-15C), of dark or black features whose exact origins are not always easy to determine, and most important, of particular prominence. The latter, the prominence of the Black Madonna, is mostly due to the allegedly miraculous character of the image.

Among the miraculous Marian images are the so-called "Black Madonnas." Many of these images are quite popular among the faithful. Of the hundreds which presently exist at various shrines, some of the better known images are: Our Lady of Altötting [Bavaria, Germany]; Our Lady of the Hermits [Einsiedeln, Switzerland]; Our Lady of Guadalupe [Mexico City]; Our Lady of Jasna Gora [Czestochowa, Poland]; Our Lady of Montserrat [Spain]; and Our Lady of Tindari [Sicily].

In the early days of the 'comparative religions' discipline, authors casually equated the 'Black Virgins' venerated by Catholics with pagan goddess images of similar appearance, providing some with a polemic argument against the Catholic Church. More recently, some feminist writers have suggested the Black Madonna as indicating a perspective on Mary underemphasized in traditional Christian doctrine. In any case, Black Madonnas have proved themselves as devotional aids within ecclesial life over the course of centuries. Many of these images have received approval from ecclesiastical authority in light of the divine approval manifested by well-attested miracles (subsequently approved by Church leadership).

History of the Black Madonna Genre

Important early studies of dark images in France were done by: Marie Durand-Lefebvre (1937); Emile Saillens (1945); and Jacques Huynen (1972). The first notable study of the origin and meaning of the so-called Black Madonnas in English appears to have been presented by Leonard Moss at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science on Dec. 28, 1952. Amazingly, all the images in Moss' study had a reputation for miracles. Based on a study of nearly one hundred samples from various parts of the world, Moss broke the images into three categories:

1) dark brown or black madonnas with physiognomy and skin pigmentation matching that of the indigenous population.

2) various art forms that have turned black as a result of certain physical factors such as: deterioration of lead-based pigments; accumulated smoke from the use of votive candles; and accumulation of grime over the ages.

3) residual category with no ready explanation.

That a certain percentage of black images falls into the first group seems self-evident. For example, many African images of Mary depict her racially as a Black woman. This particular racial depiction is also apparent in many of the ethnic crèches in the Marian Library collection. Also, the famous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe from Mexico, although not necessarily intended to depict Mary's race as Black, was included in this class by Moss.

The second explanation is frequently cited by Catholic non-experts in relation to particular images. Though overused, it certainly applies to a certain percentage of Black Madonnas. The famous statue of Our Lady of the Hermits in Einsiedeln, Switzerland illustrates this phenomenon. After evacuation to Austria in 1798 to escape the designs of Napoleon when the Madonna was returned in 1803, she was found to have been cleaned during her stay in Bludenz. It was promptly decided that she should be restored to her wonted blackness before being exposed once more to the gaze of the faithful.

Similarly, the statue of Our Lady of Altötting was rescued from the ravaging of the church by flame in the year 907. This might account for the darkened features, though Moss has his doubts. If not the image at Altötting, other Black Madonnas were certainly altered in appearance after 'miraculous' rescues from burning churches.

After accounting for images which fall into the first two categories, we are left with a number of black Madonnas still requiring explanation. As Moss notes: "It is difficult to rule out artistic license." In the absence of texts stating the artist's intent, only speculation is possible. However, assuming that some of the images were darkened intentionally, we may attempt some explanations. There seem to be two particularly strong theories.

The first is that the images were darkened to illustrate a text from the Song of Songs: "I am black but beautiful." [Negra sum sed formosa] In support of this theory, note that many of the black Madonnas exist in France, and date from around the time of the crusades, when Bernard of Clairvaux wrote numerous commentaries on the Canticles, comparing the soul to the bride, as well as many on Our Lady. He was also known to have visited several shrines of the Black Madonna, for example: Chatillon and Affligem. In the Gothic period texts explicitly interpreted the Bride in Canticles as referring especially to Mary. Once artistic precedent had been set, subsequent black Madonnas may be explained by artistic convention rather than theological motivation. Based on historical correlations, Ean Begg speculates that the genre developed from an esoteric popular religion common among the Templars and Cathars, perhaps as a complement to the impetus from Bernard.

The other prominent theory is briefly summarized by Stephen Benko: "The Black Madonna is the ancient earth-goddess converted to Christianity." His argument begins by noting that many goddesses were pictured as black, among them Artemis of Ephesus, Isis, Ceres, and others. Ceres, the Roman goddess of agricultural fertility, is particularly important. Her Greek equivalent, Demeter, derives from Ge-meter or Earth Mother. The best fertile soil is black in color and the blacker it is, the more suited it is for agriculture.

Were these images taken as-is, renamed [baptized as it were] and reused in Christian worship? If so, the practice seems compatible in spirit with the norms on inculturation given by Pope St. Gregory the Great in a letter to priests written in 601:

It is said that the men of this nation are accustomed to sacrificing oxen. It is necessary that this custom be converted into a Christian rite. On the day of the dedication of the [pagan] temples thus changed into churches, and similarly for the festivals of the saints, whose relics will be placed there, you should allow them, as in the past, to build structures of foliage around these same churches. They shall bring to the churches their animals, and kill them, no longer as offerings to the devil, but for Christian banquets in name and honor of God, to whom after satiating themselves, they will give thanks. Only thus, by preserving for men some of the worldly joys, will you lead them thus more easily to relish the joys of the spirit.

We may even wonder whether pagan statues of Mother and Child were thought to represent someone other than the Virgin Mary and her Son, Jesus. For Roman Catholics, Mary is "The Woman." (cf. Jn 2 and 19) Similarly, the only child worthy of special note is "The Christ Child." Lacking explicit identification, it seems natural that Christians read these perspectives into any art they saw. In fact, it seems that Eusebius of Caesarea took advantage of this predisposition and, sublimating any pagan roots [which he considered likely], used an image of the black Madonna as preparatio evangelii or evangelical preparation, a readily accepted introduction to the full Christian mystery, which is indeed centered on the Word's Incarnation through Mary.

Far from condemning the phenomenon, Benko, a non-Catholic, goes even further in validating this example of inculturation. He begins by noting the Judeo-Christian roots of the earth-mother concept in Adam's creation in Genesis 2:7. Benko sees a parallel to the "New Creation" in which Christ is the "New Adam." Structurally, Mary parallels the earth of the first creation. Benko also cites Ambrose (d. ca. 390) as an explicit example: "From the virgin earth Adam, Christ from the virgin." Moss mentions a similar teaching from Ambrose's pupil: "Saint Augustine noted that the Virgin Mary represents the earth and that Jesus is of the earth born." A number of similar examples could be cited from the Christian Tradition in and around Syria. For example, the following is from the Maronite Liturgy:

The Lord reigns clothed in majesty. Alleluia.

I am the bread of life, said Our Lord.

From on high I came to earth so all might live in me.

Pure word without flesh I was sent from the Father.

Mary's womb received me like good earth a grain of wheat. [emphasis mine]

Behold, the priest bears me aloft to the altar.

Alleluia. Accept our offering.

Benko continues:

"Earth is not only the source of fertility and new life. It is also an agent of death ... everything comes from earth and returns to it. This is ultimately what lies behind the saying of Paul, 'What you sow does not come to life unless it dies.'"

Along similar lines, Benko mentions Genesis 3:19 as closely related to the Creation account of Genesis 2:7. The agricultural cycle images death and new life, themes closely connected the paschal mystery of Jesus. Indeed, some early Christian writers used pagan myths of life reborn from death, like the Phoenix rising from its ashes, as preambles to the announcement of Jesus' story.

Conclusion

We received the following commentary to add to this information:

"Concerning why is she black--in Aramaic the language of Jesus--black means 'sorrowful'. It is a language of idioms. This links the Blessed Mother to Isis who was called 'sorrowing' in her search for Osiris."

For further information on Black Madonnas, refer to The Cult of the Black Virgin (1985) by Ean Begg; Mother Worship:Themes and Variations (1982) by James Preston (ed.); and The Virgin Goddess (1993) by Stephen Benko.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.