Antiphons

Antiphons

The research for Antiphons was done by Sister M. Jean Frisk, Schoenstatt Sisters of Mary.

In the Liturgy of the Hours of the Catholic Church, there are four seasonal antiphons sung to the honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary, asking her intercession before the throne of God and her Divine Son, Jesus Christ. The following article gives the historical background of the antiphons:

Introduction

Alma Redemptoris Mater

Ave Regina Caelorum

Regina Coeli

Salve Regina

Michel Huglo in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians gives the definition of antiphon: "In Latin Christian chant generally, a liturgical chant with a prose text, sung in association with a psalm" (47)..."derived from the classical Greek antiphonis ('resonating with')" : "And in later Christian texts, the term 'antiphonia' was used to mean 'antiphony', or psalmody sung by two choirs, perhaps to distinguish it from responsorial psalmody, performed by a soloist." It was used in early Christianity as a type of liturgical worship, as is documented in Theodore of Mopsuestia (d. 428), and even as early as Ambrose (d. 397) who wrote antiphons and hymns. (p. 472)

Antiphona generally precede short chants, with texts averaging between ten and twenty-five words and simple melodies. "Several categories of antiphon developed without any link with psalmody, such as the great processional antiphons of the Gregorian processional." (p. 472, Part V)Although antiphons normally have biblical texts, these four processional antiphons express instead the devotion of the people. (p. 472)

"The composers of the antiphon melodies, like all composers of chant, borrowed the elements of their compositions from pre-existing models, and did not seek originality. The models themselves seem to have been fixed in the second half of the eighth century for Gregorian chant." (p. 473) If we were thus able to trace the antiphons to their earliest possible origin, the models for them were probably fixed in this time period.

The Marian antiphons have been sung, since the thirteenth century, at the close of Compline, the last Office of the liturgical day; they occur in groups in antiphoners and processionals, usually together with the Proper of the Assumption (August 15). They comprise a group from the early repertory of antiphons (especially those for Christmas).

The The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicans states:

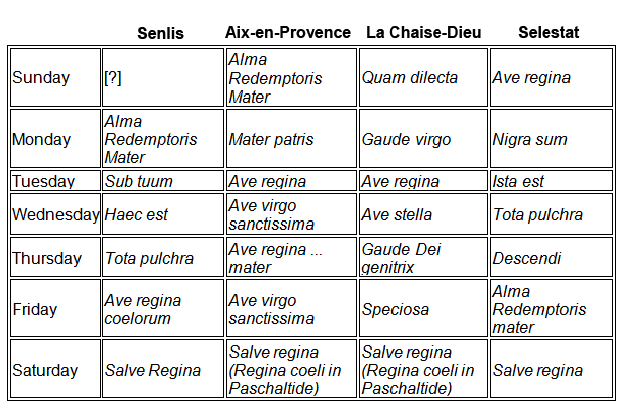

The most important of the Marian antiphons are, however, the large-scale antiphons: Salve Regina, Alma Redemptoris Mater..., Ave Regina Coelorum...and Regina Coeli.... [The best known of the four is the Salve Regina. The Cistercians chanted the Salve Regina daily from 1218; the Dominicans at Bologna chanted it daily at Compline after a miracle in 1230, and the custom was adopted by the entire Order in 1250. The chapter general of the Franciscans at Metzin 1249 prescribed all four of these antiphons for Compline, though not in the same way as in the Roman breviary of 1568; indeed, practice varied considerably in this matter, as may be seen in Table 1 [showing the distribution of the Marian antiphons in four churches in the fifteenth century].

Marian Antiphon for Advent

The manuscript tradition traces the presently known Alma Redemptoris Mater to the twelfth century. The text, however, is thought by some scholars to have been known in the late Carolingian period in France. The manuscript Ancren Riwle contains the Alma and the Ave Regina Caelorum. The Alma is also found in Chaucer's Prioress Tale.

Text

Latin:

Alma Redemptoris Mater, quae pervia caeli

porta manes, et stella maris, succurre cadenti,

surgere qui curat, populo: tu quae genuisti,

natura mirante, tuum sanctum Genitorem,

Virgo prius ac posterius, Gabrielis ab ore,

sumens illud Ave, peccatorum miserere.

English:

Loving mother of the Redeemer,

gate of heaven, star of the sea,

assist your people who have fallen yet strive to rise again.

To the wonderment of nature you bore your Creator,

Yet remained a virgin after as before.

You who received Gabriel's joyful greeting,

have pity on us poor sinners.

The Alma Redemptoris Mater is one of the four seasonal antiphons prescribed to be sung or recited in the Liturgy of the Hours after night prayer (Compline or Vespers). It is usually sung from the eve of the first Sunday of Advent until the Friday before the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord in the Temple.

The form of the poem, six hexameters with simple rhyme, was long thought to have been the style of the monk, Hermann Contractus (Herman the Lame) from the monastery of Reichenau, Lake Constance. The text also is incorporated into a Marian sequence of the twelfth century entitled, Alma redemptoris mater, quem de caelis. The sequence originated in the twelfth century in southern Germany about the same time that the manuscripts of the first musical setting of the Alma in plainchant appeared. Some authors relate the antiphon to another entitled, Ave Maris Stella [Hail, Star of the Sea].

Alma Redemptoris Mater was originally a processional antiphon for Sext in the Liturgy of the Hours for the Feast of the Ascension. It was Pope Clement VI who, in 1350, determined the pattern used today for the seasonal singing of the various antiphons.

Regarding the singing of Marian hymns and their musical settings, it has been estimated that there are fifteen thousand hymns directed to Mary. Many written to honor Mary have been based on other poems or hymns, some four thousand are original compositions. The majority of the Marian hymns were composed in Latin and sung in various modes of plainchant. It is thought that they originated as hymns of praise of the Incarnation, that is, as Christmas hymns. Alma Redemptoris Mater is one such work.

After the pronouncement regulating the seasonal presentation of the antiphons, composers more frequently grouped the four major Marian antiphons together for composition, collections and performance. During the baroque period, the settings of the antiphons gradually shifted from plainchant to more and more elaborate choir pieces. Leonel Power (d. 1445), for instance -- recorded in Germany in 1981 -- recovers an example of the shift from plainchant to pre-baroque setting. Orlando di Lasso (1532-1594) composed an intricate piece for polyphony (six voices), a triumphal piece using brass instruments. Giovanni Palestrina, praised in the post-Trent period as master of religious expression, also set the Alma in his own more reserved polyphonic style.

As a rule, composers retained the character of Advent longing and Christmas adoration in the Alma compositions. The world waits with the Virgin for the wonderment of nature to take its course. God touches earth in her and comes to us in the fullness of time.

Theological Considerations

In 1987, Pope John Paul II wrote an encyclical: Redemptoris Mater [Mother of the Redeemer]. In this letter the pope writes about Mary's pilgrimage of faith. To conclude the letter, he quotes the ancient Alma antiphon and presents it as a reflection on the wonderment of faith. The text invites us to reflect on the words of the ancient hymn and to sing them in anticipation of the turn of the millennium. For our theological reflection on this antiphon, we quote Pope John Paul II's final paragraphs from the encyclical.

51. At the end of the daily Liturgy of the Hours, among the invocations addressed to Mary by the Church is the following:

"Loving Mother of the Redeemer,

gate of heaven, star of the sea,

assist your people who have fallen yet strive to rise again.

To the wonderment of nature you bore your Creator!"

"To the wonderment of nature!" These words of the antiphon express that wonderment of faith which accompanies the mystery of Mary's divine motherhood. In a sense, it does so in the heart of the whole of creation, and, directly, in the heart of the whole People of God, in the heart of the Church. How wonderfully far God has gone, the Creator and Lord of all things, in the "revelation of himself" to human beings! How clearly he has bridged all the spaces of that infinite "distance" which separates the Creator from the creature! If in himself he remains ineffable and unsearchable, still more ineffable and unsearchable is he in the reality of the Incarnation of the Word, who became man through the Virgin of Nazareth. ...

At the center of this mystery, in the midst of this wonderment of faith, stands Mary. As the loving Mother of the Redeemer, she was the first to experience it: "To the wonderment of nature

you bore your Creator!"

52. The words of this liturgical antiphon also express the truth of the "great transformation" which the mystery of the Incarnation establishes for human beings. It is a transformation which belongs to his entire history, from that beginning which is revealed to us in the first chapters of Genesis until the final end, in the perspective of the end of the world, of which Jesus has revealed to us "neither the day nor the hour." (Mt 25:13) It is an unending and continuous transformation between falling and rising again, between the person of sin and the person of grace and justice....

These words apply to every individual, every community, to nations and people, and to the generations and epochs of human history, to our own epoch, to these years of the Millennium which is drawing to a close: "Assist, yes, assist, your people who have fallen!"

This is the invocation addressed to Mary, the "loving Mother of the Redeemer," the invocation addressed to Christ, who through Mary entered human history. Year after year the antiphon rises to Mary, evoking that moment which saw the accomplishment of this essential historical transformation, which irreversibly continues, the transformation from "falling" to "rising."

As she goes forward with the whole of humanity towards the frontier between the two Millennia, the Church, for her part, with the whole community of believers and in union with all men and women of good will, takes up the great challenge contained in these words of the Marian antiphon: "the people who have fallen yet strive to rise again," and she addresses both the Redeemer and his mother with the plea: "Assist us."

For, as this prayer attests, the Church sees the Blessed Mother of God in the saving mystery of Christ and in her own mystery. She sees Mary deeply rooted in humanity's history, in the human being's eternal vocation according to the providential plan which God has made for the person from eternity.

She sees Mary maternally present and sharing in the many complicated problems which today beset the lives of individuals, families and nations; she sees her helping the Christian people in the constant struggle between good and evil, to ensure that it "does not fall," or, if it has fallen, that it "rises again."

I hope with all my heart that the reflections contained in the present encyclical will also serve to renew this vision in the hearts of all believers...

Signed: Joannes Paulus pp.II

Marian Antiphon for the Time After the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord and During Lent

The antiphon, Ave Regina Caelorum, is sung as the concluding antiphon in the The Liturgy of the Hours from the Presentation of the Lord until Holy Thursday. It was originally sung for None for the Feast of the Assumption. The author is unknown. The earliest plainchant manuscript stems from the twelfth century. There are slightly variant versions.

Text

Latin:

Ave, Regina caelorum,

ave, Domina angelorum,

salve, radix, salve, porta,

ex qua mundo lux est orta.

Gaude, Virgo gloriosa,

super omnes speciosa;

vale, o valde decora,

et pro nobis Christum exora.

English:

Hail, Queen of heaven;

Hail, Mistress of the Angels;

Hail, root of Jesus;

Hail, the gate through which the

Light rose over the earth.

Rejoice, Virgin most renowned

and of unsurpassed beauty,

and pray for us to Christ.

Most authorities break the antiphon into two rhymed stanzas. It was a processional antiphon, and--despite its use during the solemn season of Lent--it repeatedly greets Mary in words that echo joy and confidence in her intercession. Mary is queen, lady, root, door! These words recall associated biblical allusions used in the ancient Eastern hymn, the Akathistos. She is greeted with words of increasing intensity, words which our English translation does not sufficiently render: ave, salve, gaude, valde. These are forms of greeting, acclamations, that show an increase of intensity and regard in the greeting.

Though there is little literature to be traced regarding the Ave Regina Caelorum in comparison to the other antiphons, what is said of them applies here as well. It was not the intent of the antiphon writers and singers to enhance or musically interpret a text significantly from the ninth through thirteenth centuries. These were religious forms, prayers of the most exalted type, that were to be prayed. From the fifteenth century on, the Ave Regina Caelorum text lent itself to a greater variety of musical interpretation. In the post-Reformation period, Mary began to be praised more and more as exalted queen of great beauty and dignity.

Examples of the period are found from the composers: Leonel Power (d. 1445), Guillaume Dufay (d. 1474), Tomas Luis de Victoria (1548-1611), for example; Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) also created a powerful setting for the Ave Regina Caelorum.

Theological Considerations

What is said of Mary is said in relationship to Christ. He is the King. Mary reflects his kingship and by a journey of faith, she may share in his kingship, both its agony on earth as she stands at the foot of the cross and its glory in the eternal kingdom. Her choice to be Christ-centered and God-bearer gives her a dignity above the angels. She is of Jesse's root from whom the Savior will come. Her womb is the gate from whom the true Light, Jesus Christ, was born.

Mary not only bears Christ, but also has been graced by him and because of him, she has been given the fullness of beauty. She is the glorious virgin, loveliest in heaven, "fairest where all are fair." All are called to be filled with Christ, we among them, Mary preeminently so because of her role in the plan of salvation. It is the Christ life, his grace, God alone, who is beauty beyond all measure.

The human person looks at Mary and rejoices with her that he has graced her so wondrously. We ask her to remind her son of our needs and to pray for us to Christ.

The Ave Regina Caelorum Today

Although many musical settings of the Ave Regina Caelorum abound, it is the least known antiphon as a prayer or as a popular hymn. As mentioned above the antiphon is sung in plainchant during the Lenten season. Mary, in all her dignity and loveliness, should walk this way with us. Even in the midst of her deepest sorrow, while she shares the destiny of her son, her dignity and her beauty is not crushed. She accompanies Christ--and us--through the painful periods of life. The antiphon reminds us to pray with Mary to the God of life, our living redeemer, Jesus Christ. He has won the final victory of life over death. She and we may share this victory.

Marian Antiphon for the Easter Season

The Regina Coeli is one of the four seasonal antiphons of the Blessed Virgin Mary prescribed to be sung or recited in the Liturgy of the Hours after night prayer (compline or vespers) from Holy Saturday to the Saturday after Pentecost. The Latin text of the sung Regina Coeli (sometimes written Caeli) follows:

Text

Latin:

Regina coeli laetare, Alleluia,

Quia quem meruisti portare. Alleluia,

Resurrexit sicut dixit, Alleluia.

Ora pro nobis Deum. Alleluia.

English:

Queen of heaven, rejoice, alleluia:

For He whom you merited to bear, alleluia,

Has risen, as He said, alleluia.

Pray for us to God, alleluia.

As H. T. Henry states in the 1911 Catholic Encyclopedia, "The different syllabic lengths of the lines make the anthem difficult to translate with fidelity into English verse. The prayer form makes an addition at its conclusion which parallels the Angelus prayer. Two forms of the conclusion in the English recited prayer form are also included here:

Rejoice and be glad, O Virgin Mary, Alleluia.

For the Lord has truly risen, Alleluia.

Let us pray: O God, who by the resurrection of Your Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, has been pleased to fill the world with joy, grant, we beseech You, that through the intercession of the Virgin Mary, His Mother, we may receive the joys of eternal life, through the same Christ our Lord. Amen

V. Rejoice and be glad, O Virgin Mary, alleluia.

R. Because the Lord is truly risen, alleluia.

Let us pray:

O God, who by the resurrection of Your Son, Our Lord Jesus Christ,

granted joy to the whole world: grant, we beg You, that through the intercession of the Virgin Mary, His Mother, we may lay hold of the joys of eternal life. Through Christ our Lord.

Historical Origins

The Regina Coeli is the most recent of the four evening antiphons. In written form the Regina Coeli can be traced to the twelfth century. Most sources indicate that it was probably an adapted Christmas antiphon. The authorship is unknown. "Legend says that St. Gregory the Great (d. 604) heard the first three lines chanted by angels on a certain Easter morning in Rome while he walked barefoot in a great religious procession and that the saint thereupon added the fourth line: 'Ora pro nobis Deum. alleluia'." Marienlexikon attributes this source to the Golden Legend around the year 1265.

The authorship has also been attributed to Gregory V but with no foundational evidence. The Franciscan heritage indicates that it was used already in the first half of the thirteenth century. "Together with the other Marian anthems, it was incorporated in the Minorite-Roman Curia Office, which, by activity of the Franciscans, was soon popularized everywhere and which, by the order of Nicholas III (1277-80), replaced all the older Office-books in all the churches of Rome." Marienlexikon

Its use as a concluding evening antiphon during Eastertide dates from the mid-thirteenth century, although it first appeared in a manuscript dating from about 1200 of the Old Roman chant tradition, where it was used as the Magnificat antiphon for the octave of Easter. More specifically, the Marienlexikon states that the oldest musical score is retained in St. Peter's at the Vatican in a manuscript from 1171 (Vat. lat. 476); another, a Franciscan antiphonary dated 1235, is found in the archive of Munich's St. Anna Monastery. Thereafter it is found in many manuscripts of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

An interesting note found in a German source book indicates that a German translation, Frew dich, du himmel Kunigin is found in the Constance Songbook of 1600, in the 1659 Bregenz Praxis Catechistica and the Einsiedeln Songbook of 1773. The German hymn had seven stanzas and was considered a translation of the Marian antiphon Regina caeli Laetare.

In 1742, Benedict XIV decreed that the Regina Coeli was to be prayed in the Easter season during the ringing of the Angelus bell. "In the prescribed regulation, to pray the Regina Coeli always standing, is a continuation of the oldest form of Easter prayer." [Fischer, 1097-8]

Theological Considerations

Three sources were rich in supplying theological reflection for the Regina Coeli. The words Regina Coeli are best translated Queen in Heaven. It is an Easter title of honor and signifies that the Mother of Christ already participates in the Easter glory of her son. Instead of the usual address for Mary, Ave, the Laetare, rejoice, is used. This is an invitation to look to Mary as she lives now: the servant of the Lord on earth has become queen of heaven. In her exaltation, she has become a sign for all who are united with Christ through baptism. As the preface for the August fifteenth feast of the Assumption says, "the virgin Mother of God was taken up into heaven to be the beginning and the pattern of the Church in its perfection." All of the baptized can look forward to this promise. The antiphon reminds Mary, the crowned mother of the redeemer, of the promise fulfilled by using the angel's words, "He has risen as he said!" (Matthew 28,6) The antiphon ends with a petition for intercession, "pray for us to God. Alleluia!"

Pallottine priest, Franz Courth, in his extensive article on Marian prayer forms ("Marienkunde," c. 1984), speaks of the originality of hymn prayer-hymn praise. He says, "Hymn prayer is not a speaking about, but is a personal address, it is a praising acclamation." (p. 388) To sing, especially to sing praise, expresses the fundamental attitude of admiration, gratitude and dependence, also the readiness to imitate. This he applies to Mary.

It is also noteworthy that Martin Luther makes reference to the Regina Coeli in his critique of Marian prayer. For Luther, it is simply too much to give to a creature what belongs to God alone. The reformers were accustomed to changing the text from Marian to Christ hymns, typical of the liberties taken with music everywhere, that is to change text, but retain melodies. Among many famous composers who put the Regina Coeli to music are W. A. Mozart as well as Mascagni in the Easter procession of his opera, in his Cavalleria Rusticana [Rustic Chivalry].

In Catholic thought, on the other hand, for Erasmus Sarcerius (1501-59), the Regina Coeli is the epitome of a correct understanding of Mary whereby the Mother of Jesus has deserved (meruisti) her election. Catholic thought will eventually incorporate the discussion of Mary's queen ship with that of her dignity as expression in the Immaculate Conception. The musical expression will develop from the flowing simplicity of the chant to the triumphal masterpieces of the Baroque period.

The Regina Coeli Today

The antiphon is sung in several variations today. The plainchant prayer form is used weekdays during the Easter season. For the Easter solemnity, the later musical forms of polyphonic and ornate styles are used. The chant gives a sense of joy and delight. After the long, heavy season of Lent, the joy of Resurrection must resound. There are few words. With Mary, we rejoice. The musical settings used for Sunday and the Easter Liturgy itself are majestic and powerful. There is no doubt about the power of life and its fulfillment in Christ's Resurrection. Mary is asked to pray for us that we become part of it one day.

The Regina Coeli, especially as we sing the various forms in our faith community during the season, is a simple plea as we turn to Our Lady as a queen who can pray for us. She is a queen of joy and rejoicing because He is risen -- all of these aspects contribute to the whole hope of our faith. Lent is over; death is over; fasting and the somber season is over. It is time to sing with Mary, to grow quiet in her prayer, and to know that there is sure hope that our destiny may share this Resurrection.

Marian Antiphon for Ordinary Time [Easter to Advent]

The best known and perhaps most frequently sung antiphon is the Salve Regina. Reference was made to the hymn in the introduction above. It is prescribed from Trinity Sunday (after the Easter season) to the eve of the first Advent Sunday. It is attributed to a wide variety of authors: Bernard of Clairvaux, Peter of Compostela (b. 930) who may have translated it from the Greek, Adhemar de Monteil of Puy (ca. 1080), Hermann the Cripple, Athanasius, John Damascene, and Pope Gregory IX. The earliest known manuscript was found at Reichenau, latest early eleventh century.

There are legends attached to the Salve Regina, which attest to its popularity: Jean l'Hermite dreamt that Bernard of Clairvaux heard the entire hymn sung by heavenly choirs; he then repeated the words to Pope Eugene III. In an extension of this legend, it is reported that Bernard visited the great cathedral of Speyer in 1146. When he entered the cathedral, he reverenced Our Lady's statue, chanting: "O thou deboner, o thou meke, o thou swete maide Marie." [These words are found in the Cambridge primer of the fifteenth century.] Historically, the story seems unlikely, since the Swabian manuscript which preceeds Bernard, contains the entire text.

Text

Latin:

Salve, Regina, mater misericordiae;

vita, dulcedo et spes nostra, salve.

Ad te clamamus, exsules filii Hevae.

Ad te suspiramus, gementes et flentes

in hac lacrimarum valle.

Eia ergo, advocata nostra,

illos tuos misericordes oculos ad nos converte.

Et Iesum, benedictum fructum ventris tui,

nobis post hoc exsilium ostende.

O clemens, o pia, o dulcis Virgo Maria.

English:

Hail, holy Queen, Mother of mercy,

hail, our life, our sweetness, and our hope.

To you we cry, the children of Eve;

to you we send up our sighs,

mourning and weeping in this land of exile.

Turn, then, most gracious advocate,

your eyes of mercy toward us;

lead us home at last

and show us the blessed fruit of your womb, Jesus:

O clement, O loving, O sweet virgin Mary.

Historical Origins

The anitphon is associated with evening and evensong. Fr. Juniper B. Carol, OFM writes in his Mariology, Volume 3,

Its occurrence after compline is probably traceable to the monastic practice of intoning it in the chapel and chanting it on the way to sleeping quarters. (76)

Carol continues,

There is considerable evidence that the hymn was popular as a song of exultant joy, a tribute more to its lilting melody [the original plainchant is indicated here] than to its references to mourning, weeping and exile. Seafaring men doubtless came to favor it because it was so eminently singable. It came to be used as part of the ritual for the blessing of a ship, and the core of evening service on shipboard. The mention of it in Columbus' journal is well-known. (76)

This antiphon can be traced to formulas taught on missionary journeys, especially in the Caribbean. It was popular at medieval universities as evening song, and was the frequent setting for devotions known as Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. Chantries were established in the medieval and Renaissance periods for the singing of the Salve, especially on Saturday evenings. [A chantry is an endowment or foundation for the chanting of masses and offering of prayers for particular persons or intentions.]Regardless of its historical origin, it was well known and established in France and Germany by the twelfth century. It was definitely part of the liturgical prayer of many monasteries and part of the common prayer of many religious orders.

Carol writes, that the monastery at Cluny used it as "a processional hymn on the feast of the Assumption and other feasts which had no canticle proper to a saint, as the community made its way to Mary's chapel." (75)

The text has been altered slightly over the centuries. It originally began with the sentence, Hail, Holy Queen of Mercy; however, at Cluny it became, Hail, Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy. Mary was called upon to be the advocate before the Lord.

Both Erasmus and Luther found the Salve Regina too extravagent in its application to Mary's place in salvation history. As time went on, the hymn became a symbol of Tridentine mariology and Catholic Reformation devotion. The hymn was defended, sung "with a loud voice," and inserted in older manuscripts. Peter Canisius (d. 1597) countered these oppositions by writing that we praise God in Mary, namely, the work that he has done in her, when we turn to her in song.

The Salve Regina was used as the outline for Part I of Alphonsus de Liguori's treatise, The Glories of Mary, which has been published in over eight hundred editions since 1750. Each phrase was further subdivided into sections dealing with praise of Mary and turning to her as Advocate. For example chapter 6, part 2 is titled: Mary is so tender an Advocate, that she does not refuse to defend the cause even of the most miserable.

Another literary genre, known simply as The Salve, is the hymn book. After the invention of the printing press, the first hymn book published was by the Lutheran, Johannes Walter, 1524 in Wittenberg. This was quickly followed by two Catholics who privately published their own hymnals in 1537 and 1567 respectively. The first officially published Catholic hymnal was the Book of Bamberg in 1575. By 1882, a hymnal published by Bishop Joseph Georg von Ehrler, was given the official title Salve Regina, which in some south German dioceses remains true today. The four seasonal antiphons are usually found in these hymnals, which consist of devotions as well as hymns. The 1882 edition numbered 788 pages and reached forty-eight editions until it was replaced with yet another Salve Regina in 1929.

Finally, in our discussion of the hymn's history, the prayer in its vernacular forms were prescribed by Pope Leo XIII to be prayed after the low masses (that is, after masses in which there was no singing). This regulation lasted until the reforms of the second Vatican Council. Earlier history records instances of the Salve being prayed before mass, and by various religious communities, before the reading of the final Gospel.

We have yet to discuss the musical settings of the Salve Regina that developed through the centuries. The first known is the solemn plainchant. Since both the solemn and simple plainchant were so familiar and much loved, this may have contributed to the fact that relatively few musical settings (in comparison to the Regina Coeli, for instance) took root or grew in popularity for liturgical use. The plainchant Salve, unlike the other antiphons, can be found in troped versions, that is, by intermingling expanded text with the original base text. A Munich manuscript typifies this: Salve virgo virginum, Virgo clemens, Dulce commercium, Tu es ille fons signatus, [Hail Virgin of virgins, merciful virgin, sweet exchange, you are the sealed fountain.] These texts of the Fathers of the Church, with their biblical illusions to the Songs of Songs, are interwined with the text of the antiphon. Examples of the hymn are found in every period. Examples: Leonel Power, d. 1445; Johannes Ockeghem, d. 1496?; Orlando di Lasso, d. 1594; Joseph Haydn, d. 1809; Marcel Dupre, d. 1971. The patterns of interpretation as discussed for the Regina Coeli are applied also to the Salve Regina.

Theological Considerations

Chapter 8 of Lumen Gentium during the Second Vatican Council, pointed out Mary's role among the People of God. The ancient term Advocate, used by the Fathers and a title given to Mary in the Salve Regina, was quoted in paragraph 62. The Catechism of the Catholic Church devotes several paragraphs to Mary. Mary is a "preeminent and...wholly unique member of the Church"; indeed, she is the "exemplary realization" (typus) of the Church. (967)

Her role in relation to the Church and to all humanity goes still further. "In a wholly singular way she cooperated by her obedience, faith, hope, and burning charity in the Savior's work of restoring supernatural life to souls. For this reason she is a mother to us in the order of grace." (LG 61; CCC 968)

"This motherhood of Mary in the order of grace continues uninterruptedly from the consent which she loyally gave at the Annunication and which she sustained without wavering beneath the cross, until the eternal fulfillment of all the elect. Taken up to heaven she did not lay aside this saving office but by her manifold intercession continues to bring us the gifts of eternal salvation... Therefore the Blessed Virgin is invoked in the Church under the titles of Advocate, Helper, Benefactress, and Mediatrix." (LG; CCC 969)

This is the meaning of the Salve Regina. It is our belief that she has been drawn to heaven but does not forget those who still journey on this earth. She can assist us only because God so wills it. She reflects for us the promises of God, that God makes to all human beings. One day our hope will be rewarded, our trials ended, as were Mary's. We look to her and ask: When our exile is done, O Maria! Show us your Son!

The Salve Regina Today

The plainchant Salve Regina is well known by those who pray the official prayer of the Catholic Church, The Liturgy of the Hours. Members of religious communities, those in seminary formation, many lay groups, etc. know and sing the Salve to conclude meetings or prayer at the end of the day. Many of the faithful elect to pray a form of the Salve Regina to close the Rosary devotion. We gather, the saints and sinners of earth, with the angels and saints of heaven, to thank the woman who brought us Jesus Christ, the Way, the Truth and the Life, and to ask her to graciously help us to know him, love him and serve him as she did.

Perhaps we can identify with a quote from Alphonsus di Liguori's Glories of Mary:

Blessed Amadeus says, 'that our Queen is constantly before the Divine Majesty, interceding for us with her most powerful prayers.' And as in heaven 'she well knows our miseries and wants, she cannot do otherwise than have compassion on us; and thus, with the affection of a mother, moved to tenderness towards us, pitying and gentle, she is always endeavoring to help and save us'. (167)

Books

Dictionary of Mary, Catholic Book Publishing, 1985.

Handbuch der Marienkunde, Regensburg,Verlag Froedrocj Pustet, 1984.

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Macmillan Publishers,1980.

Katholische Kirchenlieder: Quellennachweis von Texten und Melodien, Herder, 1930.

Marienlexikon, EOS Verlag, 1993.

Szoverffy, Josef, Die Annalen der Lateinischen Hymnendichtung, Berlin, 1965

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.