Grace of an artful life

I was a wide-eyed 10-year-old with a huge afro and skinny legs set on attending a summer art program at the Dayton Art Institute. Over breakfast, I’d badger my mom: “Can I go?” I’d ask her again at dinner: “Can I go?” I’d bring it up in the car. I asked her until she understood how important it was for me. And then my parents signed me up.

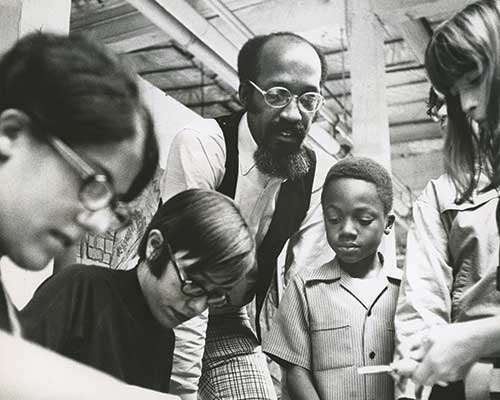

I took my seat in the bright and airy printmaking studio and was overcome by the basketball-player-sized art instructor who entered the room. His open and engaging smile invited us all to take a chance and make our first silk-screen prints on fabric. I chose lime green ink on a burgundy background for my repeating pattern of pyramids and palm trees. In my memory, there is a camel in the scene.

I remember the instructor watching my art, appraising the vibrant contrast of colors and affirming the boldness of my first project.

Willis “Bing” Davis, 86, was our instructor that summer more than four decades ago. Davis believed that every one of us in that studio possessed a creative vitality that could be harnessed and unleashed. He teaches art without care as to whether we’ll become professional artists, believing that doing art leads us to be better human

beings.

As a gourmet chef of life, he feeds us at his intellectual and artistic buffet.

Through the years, Davis has been a dynamic presence in my life and that of other artists. He is a world-renowned multimedia artist, an educator and builder of communities that stretch across perceived divides, artistic mediums, continents and states of mind.

And now we all have access to the documents that reveal moments of life and breadcrumbs of genius thanks to Davis’ gift of his papers to University of Dayton Archives.

My recent perusal of the archive is but one of the many ways in which I have touched the story of Davis over these many months. Through these opportunities, I have learned that the reason to better know Davis is to better understand humanity; to better appreciate art; and to understand where he came from, what he has built and where he wants to go next. It is a daunting and monumental task, spotlighting the eight-decade existence of a national leader and international presence that I personally have admired and respected ever since our orbits crossed decades ago. Through telling this story, I aim to share with others the artist I have known and the genius I had yet to uncover.

//////////////////////////////

“You’re doing a documentary on Bing?”

My answer is yes — always with an anxious smile.

Davis is a towering presence in the Dayton community whose grace and intellect has altered the landscape of this city and beyond. Even at age 10, I felt that reality I’ve come to learn more deeply as an adult. Colin Scianamblo, the chief content officer at the local PBS station Think TV and CET studios, asked me to be the associate producer for the documentary. The task was daunting, but I said yes.

I am a native Daytonian who started on the early path to being a multimedia artist thanks to educators like Davis. I’m a choreographer whose life trajectory has surprisingly led toward a career in television as the on-air host for a weekly series on arts and culture.

How do I catalog the life of a legend? For more than a year, I have been working with a team to excavate and unearth this man’s mythology, motivations, hopes and desires.

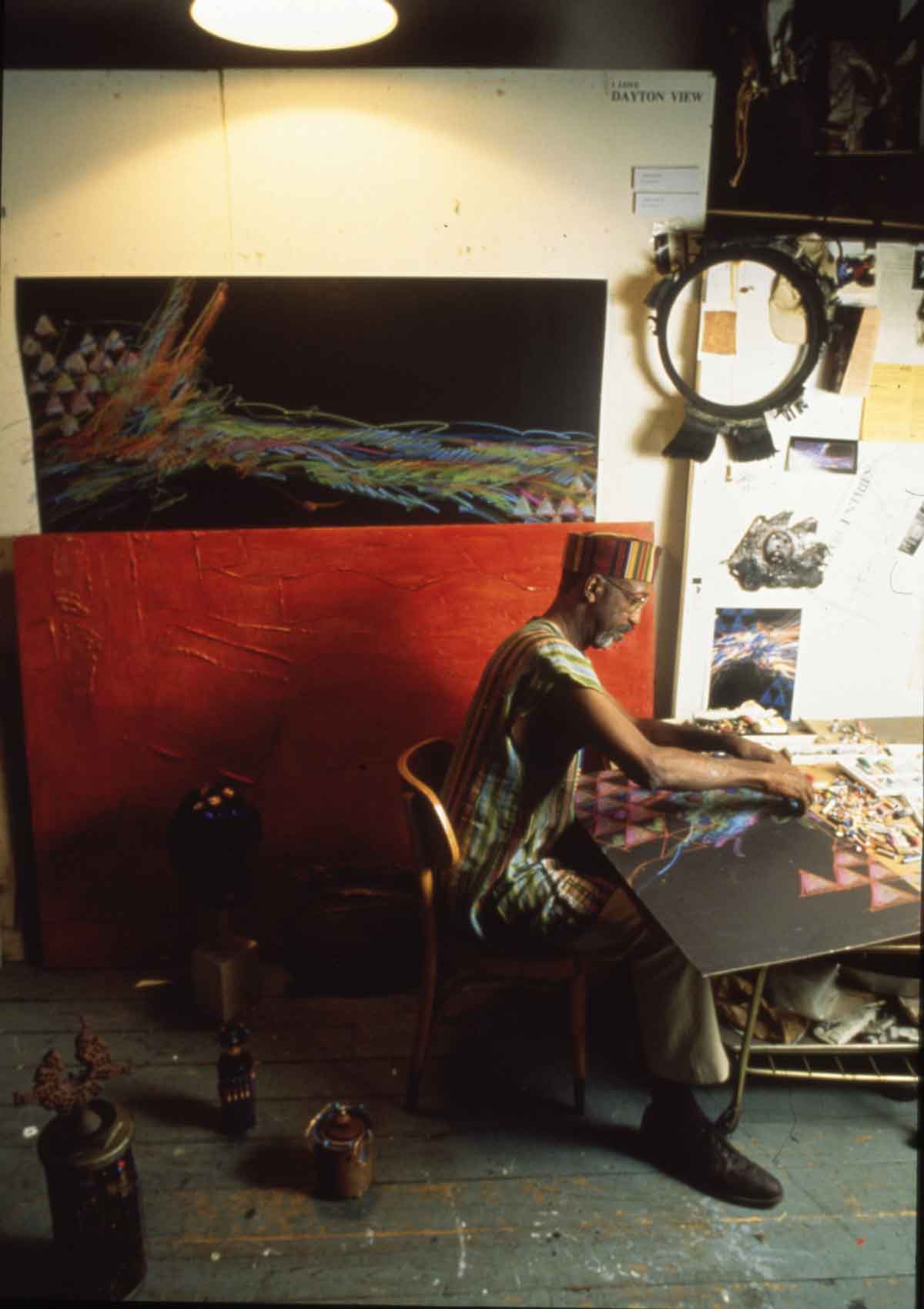

In the 1970s, Davis made a sharp statement as part of the Black Arts Movement with a response to the Attica Prison riot of 1971 that mixed dark and muted images with bright red that looks like blood on concrete. More recently, his vibrant and energetic pastel “Ancestral Spirit Dance” series transports the viewers’ imaginations on their own spiritual journey, writes Moyosore Okediji, professor of art history at the University of Texas at Austin and an expert on contemporary African diaspora art.

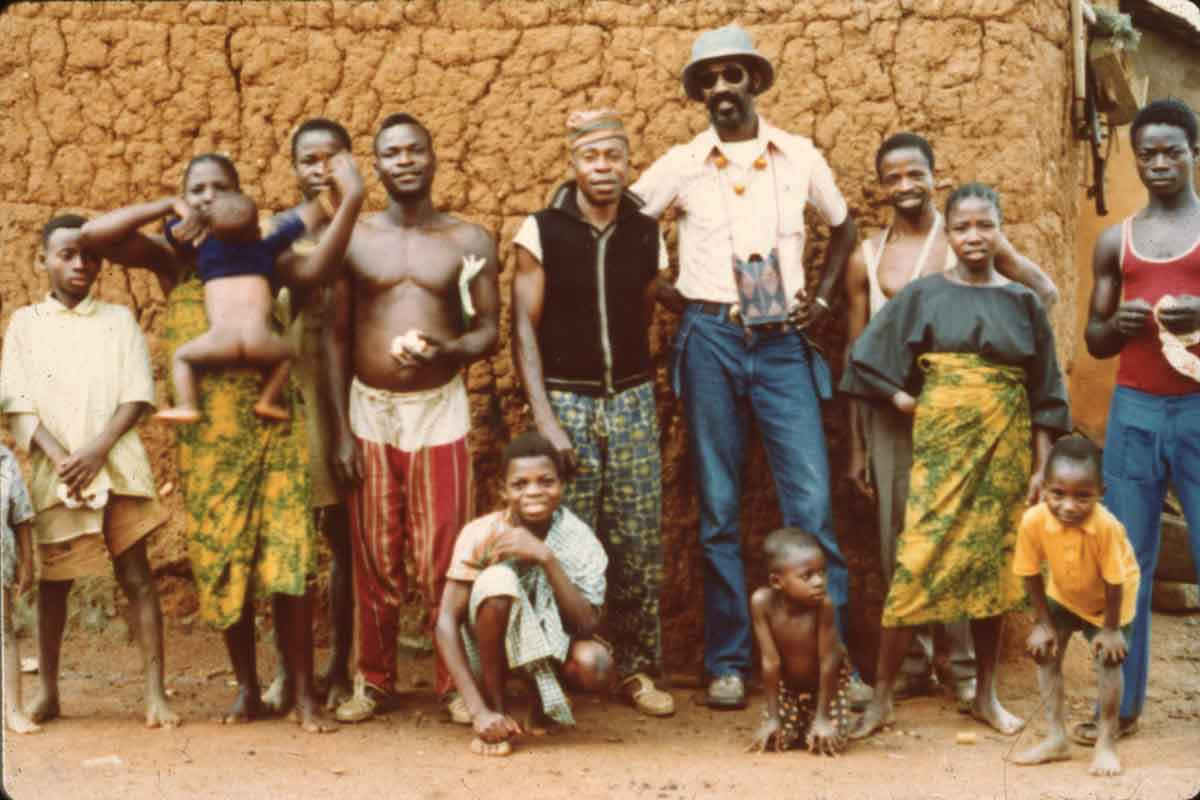

On UD’s campus, Davis’ art can be found hanging on the walls of Roesch Library and the Fitz Center for Leadership in Community. His piece “Ancestral Spirit Dance #612,” with kinetic triangle patterns in gray blue and orange, was among the works selected for Get Together, the inaugural exhibit of UD’s new Roger Glass Center for the Arts. His art is in public and private collections in the U.S., England, China, Japan, France and Australia, plus Senegal, Ghana, Nigeria, Namibia and Gabon on the continent of Africa.

What drives the relentless work ethic of Davis to create the large-scale oil pastels that hang in public spaces throughout Dayton and the country?

What compels an octogenarian to create a thorny, spike-ridden ceramic kneeling cushion in response to the Colin Kaepernick “Star Spangled Banner” controversy?

For me, the artworks are a cultural breadcrumb trail that has tantalizingly drawn in me and countless others. What societal forces produced this questioning creative genius called Bing?

His artworks are a cultural breadcrumb trail that has tantalizingly drawn in me and countless others.

It is a story that reads like a movie plot: A man raised with five siblings by a single mother — first in Greer, South Carolina, and then in Dayton — displays extraordinary athletic ability and artistic creativity. He learns and works and rises to become an internationally renowned artist, respected educator and champion for our community. It is an ultimately triumphant journey set against the backdrop of the Jim Crow-era society of the ’30s and ’40s, the march for civil rights and justice of the ’60s, and the turbulent friction of a country coming to terms with divisions of race and class in the 21st century.

//////////////////////////////

Ever the educator, Davis and his wife, Audrey, see the donation of his papers and other materials to create the Willis Bing Davis Archive at the University of Dayton as an opportunity for further exploration.

“I am excited about the potential of young people getting some insight on the journey I have taken in hopes that it informs their journey and shows them the joy of sharing what you’ve learned along the way,” he said.

The archive builds on Davis’ long relationship with UD, including as artist-in-residence, honorary Doctor of Fine Arts recipient and exhibitor.

“It provides me an opportunity to continue to impact the lives of students — that’s always been a joy of mine,” Davis said.

Archival projects are about preserving information and data that may be useful to future historians, students and your everyday curious information seeker. Davis is an educator who taught for many years in Dayton Public Schools and was a professor of art at DePauw University, Miami University and Central State University, where he was chair of the art department. His writings and essays on pedagogy reveal his philosophy to teach the human being first; the art will follow.

His writings and essays on pedagogy reveal his philosophy to teach the human being first; the art will follow.

An exploration of his papers can also be seen as the starting point to greater awareness and understanding of our purpose on this earth.

My journey through his archive happened in Albert Emanuel Hall, the patrician columned building that houses the special collections of UD. Some ground rules must be observed when pouring through the stacks of white banker boxes filled with papers and correspondences from an eight-decade journey: no pens, only pencils, and bring a cardigan in summer because the viewing rooms are temperature-controlled to protect and preserve.

This very first trip was not a solo adventure; working alongside television producer Ann Rotolante and co-producer on the documentary, we met with Kristina Schultz, our point person at the archives who worked alongside so many at the University to take possession and archive this treasure trove of materials.

On a sunny day in June, with hands freshly sanitized, we requested two boxes, one for each of us to open like Christmas presents. I removed the lid to my assigned box and breathed in the scent of old paper imbued with history. I pulled out the first manilla folder. Multiple sheets of paper lay before me: invoices, correspondence, fliers from long-ago art exhibitions and receptions. Folder after folder was filled with documents from 1955 all the way to 2019 — just not in any chronological order or rational system of organization. I began furiously writing notes and taking photos with my phone. I gathered random fragments and anecdotes from Davis’ life:

- A note from President George H.W. Bush thanking Davis for the personal tour of the Afro-American Museum at Wilberforce University in Wilberforce, Ohio.

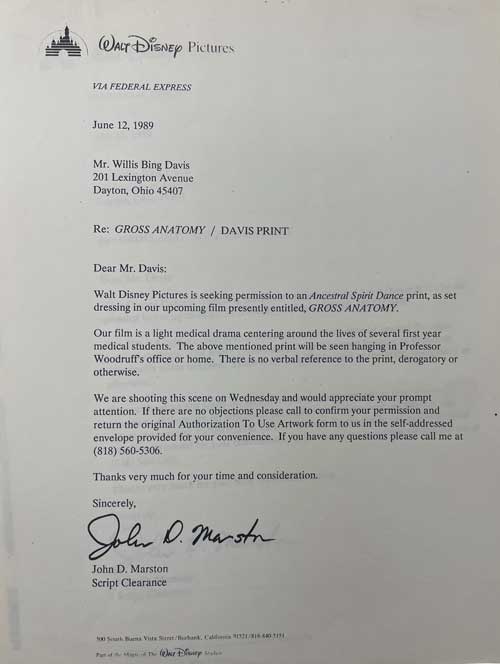

- A contract with the Walt Disney Co. to use his work on the set of the movie Gross Anatomy.

- The boarding pass and itinerary for an educational trip to China.

- Letters and correspondence with Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, celebrated American artists of the 20th century and his personal friends.

- A flier from his solo exhibition at the Studio Museum of Harlem in 1975.

- An invitation from Congressperson Shirley Chisholm to speak to the Black Congressional Congress.

That first day in June soon turned into days over many months of writing down events and dates, and of taking photographs of letters and correspondences with former students and leading figures of African American society, from Oprah to Mike Tyson. I quickly maxed out the storage on my iPhone. Box after box revealed an epic life lived on a global stage.

At every discovery, my mind was blown.

Through this research and my interviews with individuals for the documentary, I have learned many facts that provide glimpses into how pivotal Davis is in the art world. For example, he is a lifetime member of the National Council for Education for the Ceramic Arts. He advocated early for the recognition of ceramics as not just a craft but an art form. His advocacy led the National Endowment for the Arts to request Davis help it revamp its grant process for ceramic artists.

Research also revealed his importance in the Dayton community. For example, he was the first to champion the revitalized Wright Dunbar Business District. He saw the opportunity to spearhead an economic and artistic revival by being among the first to invest in and renovate a building on the historic business corridor in predominantly Black west Dayton. He opened the Bing Davis Art Studio and EboNia Gallery, which includes space for his nonprofit, Shango: Center for the Study of African American Art and Culture, for young and emerging artists.

It’s taken patience and perseverance, but Davis today counts among his neighbors a National Historical Park on the Wright brothers and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar; the Greater West Dayton Incubator for economic development; and the West Social Tap and Table, which attracts diners from throughout the city. Davis shone his spotlight to further justice and spur change in a community that craved rejuvenation.

//////////////////////////////

Every interview for the documentary was a wonderful gift. That included all our conversations with Davis.

As we sat down with Davis in the sanctuary of Mount Pisgah — the church where he is its longest-serving member at 86 years and counting — you could sense his ease and comfort in being in this sacred space. A flood of memories about family and community poured out from him. We had scheduled a one-hour conversation, but it turned into two-and-a-half hours of revelations that even caught him off guard.

Among the revelations that surprised both the camera crew and Davis was his story about those in his life who pushed him to do great work. He talked about his mother, of course, a strong African American woman raising her family in east Dayton. Then his journey through memory revealed the other women who shaped his life. They were the mothers in the neighborhood who watched him from their windows and porches to be sure he stayed safe — and stayed out of trouble. They were his staunchest guardians and his keenest champions, he said. Like most Black men of his time, he fully expected to drop out of school at age 16 and take up a job in the meat-packing plant. Instead, they told him, “You are better than that. You have more to offer the world.”

People take prominent roles in the story of Davis’ life and in the influence he’s had on others. A certain serendipity occurred rather frequently for me during this journey; on the production, we called it the “Bing effect.” We just had to say his name aloud and members of the community pledged support instantly. They provided firsthand accounts of his special brand of magic.

Among them is Amy Minehart, an art teacher in Yellow Springs, Ohio, who invited our camera crew into her classroom this spring. Every year, she uses Davis as source material, inspiring her students to create art in the style of Davis’ work. She is among the teachers of the Ohio Alliance for Arts Education who take workshops from Davis. Through his teachings and classroom collaborations, he has kindled in students from throughout the state an exploration of their lives through art.

We encountered story after story of Davis altering the life trajectory of — or at least having made lasting impressions on — countless people. For me, that opportunity came again when I was a professional artist in my early 40s. It was a joy for me to choreograph a dance to honor Bing and Audrey at an event at Sinclair College.

It doesn’t matter if I am attending a ballet performance or a free concert on the lawn of Levitt Pavilion in downtown Dayton; people from all walks of life, from the janitor to the CEO, all want to share their encounters with Davis. When we started fundraising for the documentary, we discovered a multicultural tribe of “Bing disciples” eager to embrace and support the project and share his energy that had inspired them.

//////////////////////////////

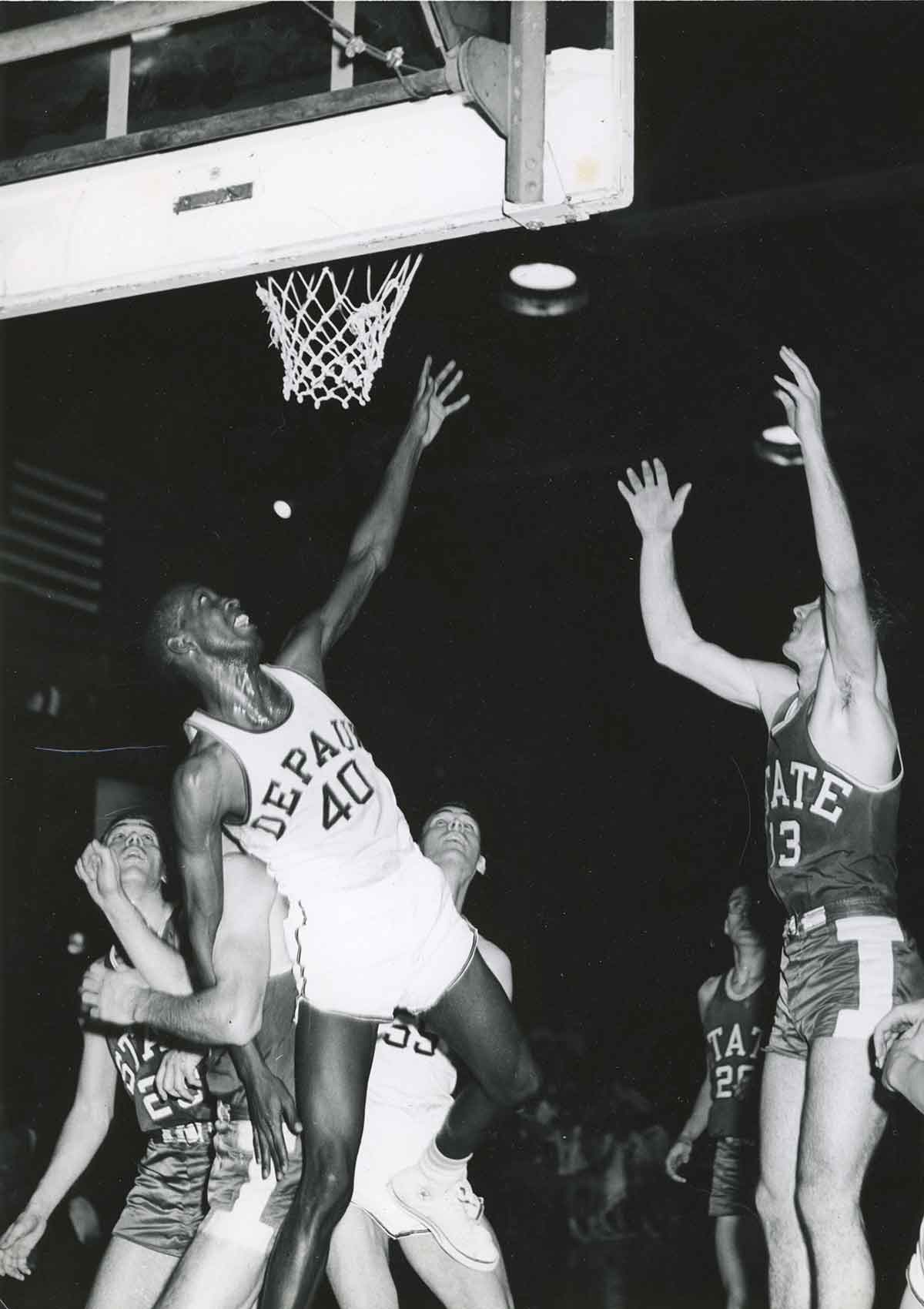

Over the days that turned into weeks and now months after having searched scores of boxes and file folders, and having talked with dozens of people whose lives he touched, my anxiety at having to translate such a life onto film has evaporated and been replaced with another concern: How do we share this story without it coming across as a work of fiction? His protean artistic output rivals Picasso’s. His All-City basketball honors in Dayton led him to a Hall of Fame career on the DePauw University basketball team and opportunities to pursue a professional basketball career. He even performed in a doo-wop group in the 1950s.

As I sit in my overstuffed home office, I begin to look at my notebooks, journals and photographs of only five decades of existence. They are relics of my own artistic output: sketches, paintings, photos, videos. I relive nervous memories of the first ballet I ever created, Okavagio; expectant memories of my first artist residency in collaboration with the University of Dayton; joyous memories of my first solo art exhibition at the Springfield Museum of Art. The physical artifacts of our time on this earth possess our spirits and intentions; the outward manifestations of our hopes, dreams and, sometimes, disappointments.

The physical artifacts of our time on this earth possess our spirits and intentions; the outward manifestations of our hopes, dreams and, sometimes, disappointments.

What the archives of Willis “Bing” Davis have shown us is a man at peace with himself. He does not define himself by objects and material possessions and has instead moved into an enlightened sense of grace, a deepening of the grace he has always possessed. He is at a place where he can receive the gifts, accolades and rewards we bestow on him and jointly celebrate his humanity. He offers us an ark, a vessel filled to the brim.

I have come to accept that the success of this documentary film ultimately doesn’t matter because it is a part of something bigger than we could have ever imagined. This film and the archives will ultimately become two parts in the exploration and understanding of all aspects of the life served that becomes the gospel of Bing. It is a testimonial map of love, life, art, sacrifice and service that this legend continues to build upon. When this documentary airs in fall 2024, I hope many more people will embrace the idea that life is better with Willis “Bing” Davis thanks to what he has given us.

Rodney Veal is an independent choreographer and interdisciplinary artist who serves as adjunct faculty for dance at Sinclair College. He is associate producer and host of The Art Show on Dayton’s PBS station, ThinkTV. The documentary on Willis “Bing” Davis will premiere at UD’s Roger Glass Center for the Arts this fall. It will also air on ThinkTV and will be available to be streamed at thinktv.org.