Herbert Martin: Good poems to sell

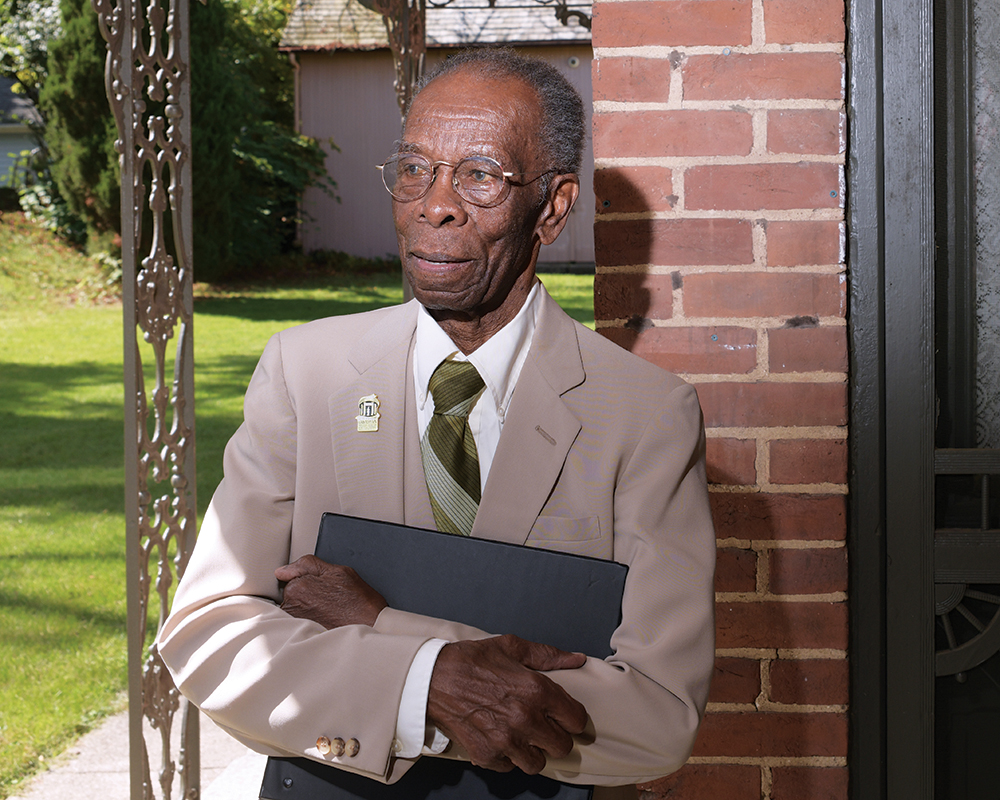

University of Dayton English professor emeritus Herbert Martin talks about his life and his new poetry collection The Shape of Regret.

English professor emeritus Herbert Martin has “good poems to sell.” His latest collection, The Shape of Regret ($16.99, Wayne State University Press), includes this line spoken by the ghost of poet Edith Sitwell, perched “on her pinnacle / far from hell.”

Maybe she’s just “Outside the Gate,” the title of another Martin poem, where the speaker says, “I no longer hope to get to heaven. / I want a chair placed outside the gate; / that will do.”

That’s a lot of eternity for a book Amazon tells me will take an hour-and-a-half to read, 18 cents per minute. And, though I did first read this delightfully varied collection of poems back-to-back, doing so is like drinking a row of shots, beginning with resonant nature imagery, then witticism, ode, spiritual, guffaw, 21-gun salute, kissing and compline.

Martin’s poetry demands time in the reading, preferably slowly, aloud, as the sounds are strengthened rather than diffused in air. Poets, too, demand time in their developing, as both poem and poet aspire to timelessness.

In February, Martin spoke in Dayton to my Sinclair College English class, his granddaughter Athena at his side. He Zoomed in from his home office wearing his signature Kente cloth scarf, a gift made by a former student’s grandmother. Born in Alabama in 1933, Martin is approaching his 10th decade, so he’s a member of the silent generation, the one that in the civil rights movement was anything but.

Martin moved away from Birmingham at age 12: “My dad got a letter from his sister saying, ‘Come North. You can make $5 a day, instead of $5 a week,’ so he left and came to Ohio. My mother, a month later, followed him at Christmas time.”

By the new year Martin, too, got on the train: “The Black conductors took care of especially kids who were traveling by themselves, and one came in and said, ‘We’ve just crossed the Mason Dixon line.’ I mumbled to myself, ‘and that’s that.’ I have never gone back to Birmingham, so make of that what you will.” The North, however, required that he learn to negotiate more subtle racism. He had to read between the want-ad lines: No, that church did not want a Black choir director. (Martin is also an accomplished chorister and librettist.)

But recently, all these years later, he awoke shocked that he had dreamt of Birmingham’s Bull Connor, the city’s infamous commissioner of public safety, which inspired a new poem, “The Fire Hoses,” that Martin read to my class: “The fire hoses were filled with cold water, and that those who survived such / incidents said that there was ice in that water because their bodies had been pummeled / And had bled or was sore in spots and had left them with anxious pain. / That same water could send you up against a wall or skirting or swimming down a street.” He continued in the voice of Connor: “Your blackness has been warned / No talking back, no praying, and certainly no singing.”

In his work, Martin talks, prays and sings a history, both personal and cultural, imbued with humor and regard for his fellow poets. Many poems in this collection are inspired by diverse artists: Lucille Clifton, Charles Ives, Hart Crane, Wallace Stevens, Wendell Berry and others. Martin masterfully roasts William Carlos Williams the way only a true friend from across the page could. References to Martin’s mother also echo in this collection as much as they did in his interview.

In his work, Martin talks, prays and sings a history, both personal and cultural, imbued with humor and regard for his fellow poets.

He described for students a moment of his mother’s tough love: “Once I was working at the post office in the wintertime, so that I could pay for the [tuition] that was coming up, and it was minus zero. So I got on the phone with my mother, and said, ‘It’s below zero. My toes and my hands will not move. I am freezing to death.’ She said, ‘What do you want me to do about that’? And she had a little sermon, she took a text, rain or shine, blah blah blah. I was so angry with her that by the time I hung up the phone [banging it] bang bang bang, the blood in my body began to move.” He said he worked all that day and didn’t feel any more pain. Years later, he thought, “If my mother had said, ‘Come home, my house is warm. You have a place in my house,’” he laughed, “I would have stayed at my mother’s house forever.”

Martin emphasized the importance of another piece of his mother’s wisdom: She said, “‘Make your friends early on in life when they don’t have power, when they don’t have riches, when they don’t have money, and they will stay with you forever.’ I tried to follow that edict ... so along the way I’ve had remarkable friends and remarkable teachers.” Martin also put himself in the way of his prominent poetic contemporaries, however brief the overlap in time. He spoke of attending a reading of Langston Hughes set to jazz in college. He described how when he’d visit a new town, he’d learn where the poets lived, and show up at their doorsteps. He met W.H. Auden this way, padding around in his slippers, the same footwear his fellow poets said Auden wore to readings because of sore feet.

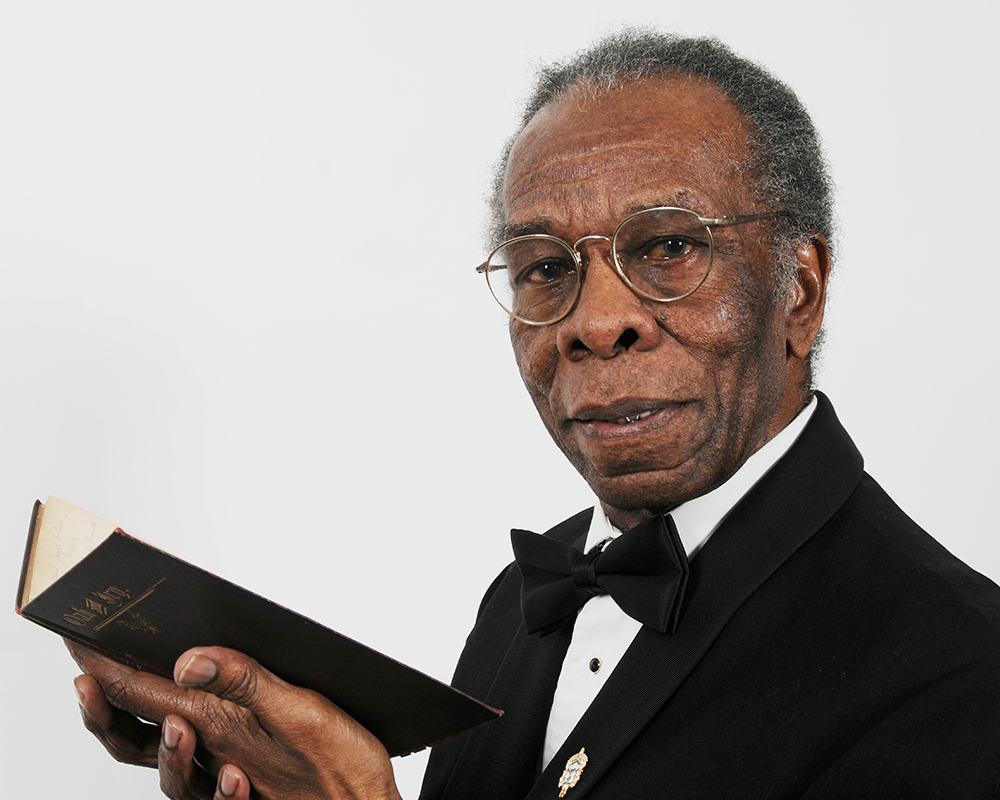

He described how poet Allen Tate once attended one of Martin’s poetry readings and advised him afterward to get himself “an old guy,” which at the time confused him. But a few weeks later he saw poet and novelist Margaret Walker read Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry. (Mmhmm. Margaret Walker. Reading Dunbar. Martin’s wife, Sue, says his good fortune warrants him a lifetime of coffee without cream or sugar.) It was there he realized what Tate meant, so Martin chose Dunbar as the artist around whom to build his scholarship. Over his career, Martin studied, collected, edited and less impersonated than embodied Dunbar, parting his own hair, donning a smart suit and tie as Dunbar did. Martin has read Dunbar’s works for years longer than Dunbar, who died at the age of 33, got to live, much less write.

Martin has read Dunbar’s works for years longer than Dunbar, who died at the age of 33, got to live, much less write.

Listening to Martin’s stories, I jealously wanted to transport into his memories, to capture the extraordinary moments from his generation, now being lost, accelerated by the pandemic. It reminded me of John Updike’s poem “Perfection Wasted,” the preemptive nostalgia for the loss of one’s “brand of magic.” Yet, while anyone can have a brand, the magic is more intense in those who are graced by some quality others lack. In Martin it’s a sort of gritty ambition cloaked in dignity. It’s the poise of a long-time churchgoer who knows he is a child of God, so he’s decided to act like one, embodying the humility and fearless grandeur simultaneously.

Martin learned much from what was grand in others. He spoke of his college literary reading: “It was as if a poet was shooting an arrow right into the heart of the thing, so we knew that that particular writer was a genius who saw many, many things that allowed him to write that perfect line.” It was with this reverence that his fellow university students pored over new poems: “Somebody would be reading, say e.e. cummings, and they would come running down the hall to show a particular poem or a particular phrase. We would wonder how in the world the poet managed to write that image. We would mull it over for months because it was so interesting and clever too.”

“We would wonder how in the world the poet managed to write that image. We would mull it over for months because it was so interesting and clever too.”

As Martin spoke, I remembered my parents talking about the release of the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper album. Through open dorm windows they heard a cacophony of the record on many turntables: Rita and Lucy and the band scrimping and saving to rent their cottage on the Isle of Wight. There was a contagious joy in shared, but curated, cultural artifacts then. In the days before virality, only excellence or tragedy broke through to everyone at the same time.

How did Martin develop his own excellence in a world that didn’t expect it, worse outright stifled it, railroading young people into particular paths? In “The Fire Hoses,” the lines he gives speaker Bull Connor include, “Go to the supplied schools given you. / Learn to cook and clean.” Even neighbors sometimes discouraged his college ambitions. Someone said to him, “You had better get yourself a broom and a mop like me and join the club.” Martin continued, “I thought to myself that there must be something better than that, and so I struggled on.”

Martin wrote a follow-up email answering a student question about racism: “I might have once upon a time been susceptible to the idea that I was not as good as, but that idea did not last long in my mind. Somehow, I knew I was talented and that I could develop that given talent” — which, he underscored, required hard work.

“I might have once upon a time been susceptible to the idea that I was not as good as, but that idea did not last long in my mind. Somehow, I knew I was talented and that I could develop that given talent.”

As my long-ago professor, Martin sent us scavenging to the library during class to discover differences among the Shakespeare quartos, dated versions of Hamlet, without consulting reference works. We returned to breathlessly report, and he listened, smiled, knowing all the answers — including how to carve out some free time while illustrating that the learning is in the struggle.

Professors and students alike endure the daily trials of teaching and learning. My friend and classmate Dana Frierson Mayfield ’95 told me of waiting just outside Martin’s office as he responded to a student’s paper or email. He narrated aloud a funny, angry comment as he typed, but then pressed the backspace key, deleting all that wouldn’t do for his legacy. In the world, closure is often thrust upon us, hence the joy in creating, revising and editing life while lived. The best of us edit more, so that what remains is precious.

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s historic Dayton home contains precious relics — souvenirs, books, his horsehair toothbrush — as well as even more poignant ones: His mother, Matilda, born into slavery in Kentucky, brought to the Ohio house a wooden rocking bench with a ridge on half the seat’s edge. It was designed to keep a sleeping baby from falling. The bench stands around the bend from the settee where her son, so young, died. Matilda’s arbor vines still produce grapes in the early summer in a backyard where, in 2022, the city of Dayton will celebrate Dunbar’s 150th birthday. Most precious, Dunbar’s poetry still graces nearly every school literature curriculum in the United States: Caged birds still sing under masks twisted into grins. The luckiest of those students heard Martin read Dunbar’s words and his own.

The speaker in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55 claims “nothing shall outlive this powerful rhyme,” yet goodness and sometimes underappreciated beauty exist in tension with perpetual, ugly infamy. In the Zoom visit, after reading “The Fire Hoses” Martin concluded his thoughts about Bull Connor’s horrific legacy for Birmingham and the world: “My faith says, this is how this poem should end. He will end with his eternity blighted with [the protesters’] memory.” He continued in the interview, discussing his own renown after shooing away any remorse with Scripture: “The rain falls on the good and the evil alike, so everyone gets what they get.” In this world anyway. Martin’s eventual eternity, whether within the Heaven’s gates or just outside them seems beyond secure, yet we’d all do well to have his lines dwell, precious and honored, in our eyes now and for years to come.

Sarah Werner Kiewitz ’96 is a professor of English at Sinclair College in Dayton. She lives with her husband, UD professor Christian Kiewitz, and two daughters in Oakwood, Ohio. A version of this essay first appeared in the online storytelling site Humans.