John Lewis, C.T. Vivian belonged to a long tradition of religious leaders in the civil rights struggle

With the deaths of Rep. John Lewis and the Rev. Cordy Tindell “C.T.” Vivian, the U.S. has lost two civil rights greats who drew upon their faith as they pushed for equality for Black Americans.

Vivian, an early adviser to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., died July 17 at the age of 95. News of his passing was followed just hours later by that of Lewis, 80, an ordained Baptist minister and towering figure in the civil rights struggle.

That both men were people of the cloth is no coincidence.

From the earliest times in U.S. history, religious leaders have led the struggle for liberation and racial justice for Black Americans. As an ordained minister and a historian, I see a common thread running from Black resistance in the earliest periods of slavery in the antebellum South, through the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s – in which Lewis and Vivian played important roles – and up to today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

As Patrisse Cullors, a founder of the Black Lives Matter movement, says: “The fight to save your life is a spiritual fight.”

Spiritual calling

Vivian studied theology alongside Lewis at the American Baptist College in Nashville, Tennessee.

For both men, activism was an extension of their faith. Speaking to PBS in 2004, Lewis explained: “In my estimation, the civil rights movement was a religious phenomenon. When we’d go out to sit in or go out to march, I felt, and I really believe, there was a force in front of us and a force behind us, ’cause sometimes you didn’t know what to do. You didn’t know what to say, you didn’t know how you were going to make it through the day or through the night. But somehow and some way, you believed – you had faith – that it all was going to be all right.”

Fellow civil rights activists knew Vivian as the “resident theologian” in King’s inner circle due to “how profound he is in both his political and biblical exegesis,” fellow campaigner Rev. Jesse Jackson recalled.

Rejecting ‘other world’ theology

Faith traditions inform the civil rights and social justice work of many Black religious leaders. They interpret religious teachings through the prism of the injustice in the here and now.

Speaking of King’s influence, Lewis explained: “He was not concerned about the streets of heaven and the pearly gates and the streets paved with milk and honey. He was more concerned about the streets of Montgomery and the way that Black people and poor people were being treated in Montgomery.”

This focus on real-world struggles as part of the role of spiritual leaders was present in the earliest Black civil rights and anti-slavery leaders. Nat Turner, a leader in the revolt against slavery, for example, saw rebellion as the work of God, and drew upon biblical texts to inspire his actions. Likewise fellow anti-slavery campaigners Sojourner Truth and Jarena Lee rejected the “otherworld” theology taught to enslaved Africans by their white captors, which sought to deflect attention away from their condition in “this world” with promises of a better afterlife.

Incorporating religion into the Black anti-slavery movement sowed the seeds for faith being central to the struggle for racial justice. As the church historian James Washington observed in 1986, the “very disorientation of their slavery and the persistent impact of systemic racism and other forms of oppression provided the opportunity – indeed the necessity – of a new religious synthesis.”

‘Ubuntuism’

The synthesis continued into the 20th century. Religious civil rights leaders like Lewis and Vivian clearly felt compelled to make the struggle for justice a central part of a spiritual leader’s role.

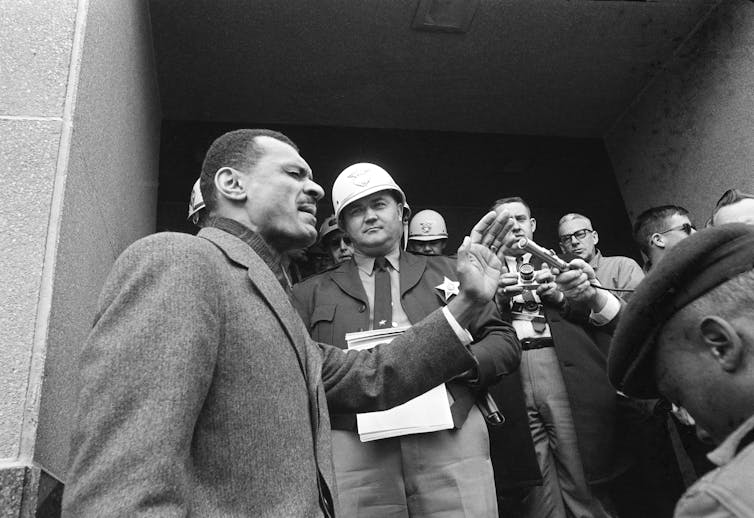

In 1965, Vivian was punched in the mouth by Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark in an incident caught on camera and carried on national news. Vivian later said: “Everything I am as a minister, as an African American, as a civil rights activist and a struggler for justice for everyone came together in that moment.”

Though their activism was grounded in Christianity, Lewis and Vivian both forged strategic and powerful coalitions with those outside of their faith. In some ways, they transcended theologically informed ideologies with a world view more akin to Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s interpretation of “Ubuntu” – that one’s own humanity is inextricably bound up with that of others.

Lewis and Vivian personified this value in their leadership styles.

George Floyd

Racial justice remains integral to Black Christian leadership in the 21st century.

After the killing of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis, it was the Rev. Al Sharpton whose words were carried across the globe, calling on white America to “get your knee off our necks” at Floyd’s memorial service.

In recent years, the Rev. William J. Barber II has been such a vocal and powerful presence in protests that some Americans consider him to be a the successor to past civil rights greats.

In an interview in early 2020, Barber said: “There is not some separation between Jesus and justice; to be Christian is to be concerned with what’s going on in the world.”

John Lewis and Rev. C.T. Vivian lived those words.

Lawrence Burnley is vice president for diversity and inclusion at University of Dayton. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.