How the Volkswagen Beetle sparked America's car-art movement

With a mariachi band playing along, the last Volkswagen Beetle rolled off the assembly line of a Mexican factory on July 10.

Originally created in Germany at the behest of Adolf Hitler, the Beetle ended up being exported around the world, and every country that sold the car absorbed it into its own culture.

In Mexico, it was dubbed the “Vocho,” and became popular among cab drivers, who painted them green and white. In France, where it was called the “Coccinelle,” or “lady bug,” it zipped through country’s winding, medieval streets.

And in America, where it was affectionately called “the Bug,” it came to represent the unconventional and idiosyncratic.

In my undergraduate history course “The Automobile and American Life,” the first image of an automobile that students see is not a Ford Model T but rather a Beetle art car featured in filmmaker Harrod Blank’s documentary “Wild Wheels.”

I show Blank’s Beetle because, to me, cars symbolize ingenuity, individuality and freedom. And art car enthusiasts like Blank – who transformed their cars into actual vehicles of self-expression – took these values to new heights.

Would Americans buy Hitler’s car?

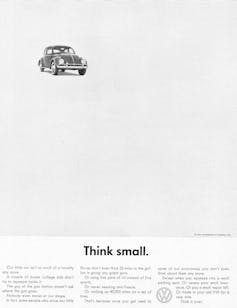

When the Beetle was first introduced to the U.S. market in 1949, most Americans hadn’t seen anything like it. Some were vaguely aware of its connection to Adolf Hitler, which wasn’t exactly a great selling point.

Aesthetically and mechanically, it was almost everything the vehicles of the “Detroit Three” – General Motors, Chrysler and Ford – were not.

Instead of being accented by sharp angles, it was round. Instead of being bulky and prone to overheating, it was economical, reliable and well-made. (Its parts were said to be put together so tightly that you needed to crack a window to close a door, and that it could float when driven into a lake.) And while most car buyers wanted a vehicle that denoted status, speed and power, the Beetle seemed exceedingly “cute.”

The Beetle was polarizing. A survey in the January 1969 issue of Road & Track magazine emphasized the divide: A majority of owners were quite satisfied with the car and indicated that they would buy another. But a number of drivers complained that the cars – especially those built before 1965 – were under-powered and slow.

For these reasons, the model always seemed to cater to a niche market; but among its fans, it achieved cult-like status.

Some owners made tweaks of their own, adding horsepower and improving the handling. Others, inspired by the car’s sublime appearance, used it to make artistic statements. One of the first was a man named Harrod Blank.

‘Oh My God’ turns heads

The son of a filmmaker and ceramic artist, Blank was born in 1963 and graduated from University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1986 with a degree in theater arts and film studies.

During the late 1980s, Blank acquired a battered VW Beetle and decided to use it as a canvas to create a work of art.

First he painted a rooster on the driver’s side door. Then he added a globe to the front ornament, mounted a television to the roof and tacked plastic chickens and fruit to the bumper. He slapped a sticker on the back that exclaimed “Question Authority” and eventually christened the car “Oh My God.”

The name referenced Blank’s eventual realization that his vehicle was not the only art car in America.

In fact, Blank’s car ended up catalyzing a movement. Its popularity brought together enthusiasts who had modified Beetles and other car models in ingenuous ways, often adorning them with discarded consumer goods.

Blank followed “Oh My God” with another creation based on a Beetle, “Pico De Gallo.” A fully interactive piece of art, the car was outfitted with two electric guitars, drums, keyboards and an accordion.

Both vehicles reflected central goals of the art car movement: to engage with the public in ways that evoke joy and wonder. Blank and his fellow art car enthusiasts hoped their cars could inspire others to reject conformity and not succumb to an increasingly homogeneous world.

A book of photos and several films, including 1992’s “Wild Wheels” and 2009’s “Automorphosis,” followed. Blank has since promoted numerous art car events, most of which have taken place in the San Francisco Bay area and Houston.

Other famous examples of Beetle art cars include one that features a wrought iron body and another that’s been outfitted with thousands of small lights.

Of course, there are many makes and models besides the Beetle that have been transformed into art cars. But for Blank and other artists, the Volkswagen Beetle proved to be an ideal canvas.

The Nazis probably never imagined that their mass-produced car would one day become the ultimate expression of creativity and freedom.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.