Like me, please

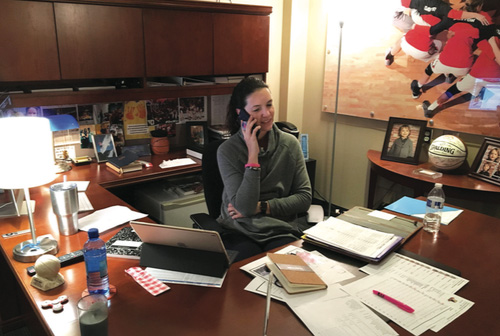

Shauna Green, the second-year Dayton women’s basketball coach, likes to keep her family time separate from her job, but carving out windows for her husband and 3-year-old son isn’t easy with recruiting having intensified the last several years.

Home was once somewhat of a sanctuary for coaches; but they know there’s now a risk of falling behind in recruiting if they allow themselves to ever truly clock out.

“It never stops. It’s always been that way in this profession, but it’s definitely more so now,” Green said. “It used to be if you talked to people who had been in this a long time, they’d go to the office to work. But if I’m out to dinner with my family and a recruit calls, I take it. My family knows that’s just part of it.

“The other night, I had a million recruiting calls to make, and I’m out in my front yard, and my 3-year-old son wants to kick the soccer ball around. I’m running around and kicking the ball and talking to recruits with my phone in my hand. You look like a crazy person, but you learn how to multitask.”

The spike in social media has been going strong for a decade or more and shows no signs of ebbing, and the NCAA recently changed its rules to reflect advances in technology.

Women’s basketball coaches can contact a recruit through calls, text messages, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook beginning Sept. 1 of the recruit’s junior year — multiple times a day if they like. The only restriction is they can’t go on Twitter and send a tweet to a recruit, although direct messages, retweeting or “liking” something is fine.

“Having done this for 15 years, I can see the difference in the last few years — just with the whole text-messaging thing. That’s really changed the game,” said Green, who led the Flyers to their first sweep of the Atlantic 10 regular-season and tournament titles last year.

“It’s nice for us as coaches because you don’t actually have to call them to get to know them, and they feel more comfortable texting than they do talking. That’s definitely a generational thing.

“I’ve had instances where you’d call a kid, and they don’t answer. But you text them, and they’ll text you right back. You go, OK, you have your phone right there because you just texted me. It makes you mad in a way, but you have to say, ‘That’s how these kids are. The way they communicate is so different.’”

Another motivation for the NCAA to ease its restrictions was to allow coaches and high school players to become more familiar with each other. And given the mounds of electronic exchanges, that’s undoubtedly happening.

If UD is interested in a prospect, the staff will follow the athlete on Twitter. If the recruit reciprocates, the Flyers know they’re in good shape.

Men’s basketball can contact players beginning June 15 after their sophomore years. And while the options seem almost endless, the UD coaches are trying to figure out what works best for them.

“What our staff still needs to get our head around is, do we want to retweet, do we want to ‘like’ this? The simple answer is ‘yes’ because we’re going to be engaged with that recruit. But at the same time, it’s a slippery slope,” said Andy Farrell, the director of scouting and program development for the Flyers.

“If you do it for one recruit, do you have to do it for all 100? ‘Dayton is retweeting so and so, why aren’t they retweeting me?’ We’ve got to be a lot more strategic with it. You see a lot of programs across the country retweeting and ‘liking’ everything, and it almost loses that touch if it’s mass-produced.”

Farrell has been on both sides of the recruiting onslaught. One of his stops before UD was at Southwest Mississippi Community College, and he learned much by seeing how his players were pursued.

“I could look at a recruit’s phone, and there would be four notifications. One’s an email, one’s a phone call, one’s a text message and one’s a social media alert. They’re looking at the social media alert first 90 percent of the time,” he said. “They’ll look at the text message next, then the missed call last.

“I’m just speaking from experience at the junior-college level. I’d say, ‘Hey, let me look at your phone real quick.’ He’d hand me his phone, and there’d be 14 unread text messages. You see the icon for 14. You go over to his social media, and there’s no red No. 1’s or red No. 4’s on those. Those were checked.

“You’ve got to utilize the different ways of communication — not saying you have to do one over the other, but I think the social-media messaging is going to be checked more frequently.”

Social media has allowed teams to get the message out about their programs quickly and effectively. UD women’s soccer assistant coach Dean Ward has found short videos — usually of Flyers scoring goals — get favorable responses.

“Nowadays, with this generation, video clips of five to 30 seconds catch their attention before they move on to the next thing,” he said. “The days are gone where you sit down and watch a video for 20 or 30 minutes. It’s all short and instant gratification and instant images.

“That’s why Instagram and Snapchat are probably the most prominent platforms right now in social media — for the kids of the age we’re trying to recruit. Things like Facebook have become an older generation type of thing.”

Asked if most high school athletes have Instagram accounts, Ward replied, “I have not met many who don’t.”

Posting game footage doesn’t seem like a chore to Ward, who was an assistant at the University of Tennessee the previous five years, because he said he’d be on his smartphone anyway.

“When I’m at home on the sofa for five or 10 minutes, I’ll kind of flip through and go to Instagram and Twitter and ‘like’ certain things from kids we’re recruiting,” he said. “After seeing kids play, I’ll try to find them on social media and follow them.

“It’s one of the things you tick off on the list — not sit down and spend two or three hours a week on social media stuff. It just kind of happens a minute here and a minute there.”

For some UD coaches, the best method for reaching recruits is still the old-fashioned way.

“For me, I don’t think it’s changed a lot,” said first-year baseball coach Jayson King, who was the recruiting coordinator at the U.S. Military Academy last year and a successful Division-II coach for 20 years before that. “I think it’s something that can help you. It’s more of a branding type of thing where people can see what you have going on and can get a glimpse inside of what you’re doing.

“But in general, it’s your standard, ‘See players, call them, get them on campus and show them what’s there and describe what the opportunity is.’”

First-year men’s basketball coach Anthony Grant, like King, doesn’t have a personal Twitter account. Predecessor Archie Miller also was resistant to becoming part of that realm.

But the team has one (@DaytonMBB), and Grant sees some value in that.

“It gives your fans and the public in general a view into your program and the things you do on a day-to-day or week-to-week basis. It gets your story out there,” he said.

One of the concerns about loosening the rules on electronic communication was that kids would be inundated with contact from coaches. But at least one UD athlete didn’t find it to be taxing.

Kendall Pollard, a senior basketball star for the Flyers last season, played for Chicago Simeon High School when texting restrictions were lifted and was encouraged by the attention he received.

“As a player, you’d like to know who’s interested in you directly. Right before that, they would send letters to the school or call my high school coach, and he would never tell me,” Pollard said.

“When coaches were allowed to [text], I was like, OK, I’m getting interest from this school and this school. When I started receiving messages on Facebook and stuff, that gave me an extra boost. I was able to see who was interested in me, and it made me go out there and play even harder.”