Punchcards, programs and pizza

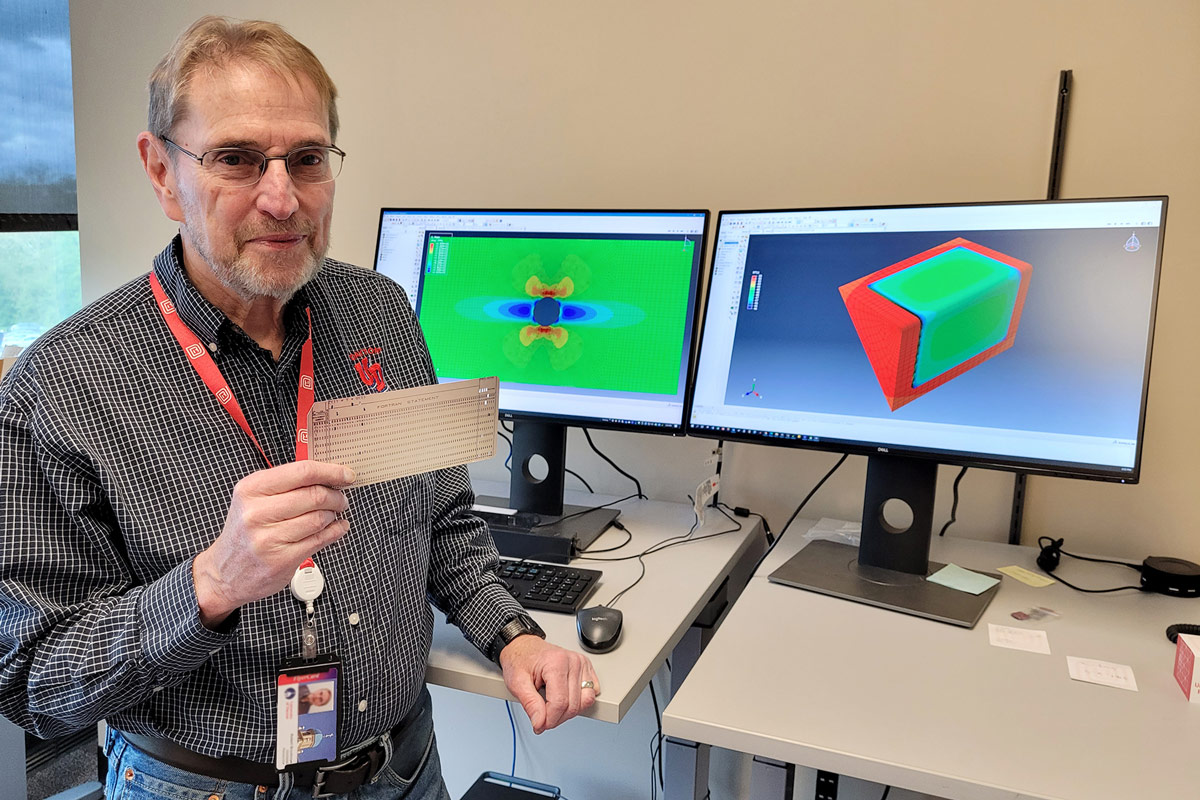

Bob Brockman holds a replica of a Fortran punch card. Today, he uses software on his PC to quickly generate models of materials and structures.

Celebrating 50 years at UDRI and the technology changes along the way

When aerospace engineer Bob Brockman joined UDRI in 1973, calculations were performed very slowly by massive computers with very low memory, and programming and results were never in the same day. Bob, who celebrated his 50th anniversary with UDRI May 4, talks about his work and how technology has made it easier over the years.

Q: What is your area of work?

Bob: I work in the general area of computational solid mechanics, which involves using computer-based models to predict the behavior of materials when they are loaded. This covers a lot of territory. The materials may be part of a building, an automobile, an airplane, an engine, a nuclear reactor, a bicycle, a tool, etc. The loading may be steady (static) forces, impact loads, fluid flow, high or low temperatures, etc. Most of what I do involves a method called finite element analysis (FEA), which allows us to build mathematical models to evaluate and predict material behavior. In the last 20 or so years, FEA has gotten pretty highly developed, and I’ve concentrated more on the mathematical models of material behavior that we need to analyze specific materials, including metals, plastics, polymers, composites and ceramics. These models become plug-ins for large commercial finite element software products, so engineers can use a familiar computer code with a better material model included.

Q: What makes your work enjoyable?

Bob: It is always interesting and usually challenging. When I first came to work at UDRI, scientific computers had hardly any memory and were very slow. The finite element technology (which is used to analyze almost everything today) was just getting started, so there was no shortage of things that had not been done before. That time was exciting because many industries were interested in using FEA to make vehicles and products better: safer, lighter, less expensive. It felt as though we were at the center of that universe.

Bob: More recently, since I’ve been more involved in material modeling, there have always been plenty of new things to do, because people were developing new materials (plastics, high-strength fabrics, composites, intermetallics, ceramic composites) that had different behavior characteristics. Think of how the materials used in the things you use have changed – in the 1960s, if something was made from a plastic material, that meant cheap and fragile; now we make things from plastics that are both light and very rugged, because the materials we can synthesize have changed so dramatically. So the challenges never go away.

Q: Is it unique?

Bob: My area of work is not unique, but it is one that I think is probably not on most people’s radar. Computational models of the type that we develop are used nowadays to design almost everything. A large fraction of my group’s work is on aircraft structures, and the most important problems have to do with how to make flight structures more reliable and safe. We have worked on understanding flight conditions that most people don’t think about, such as bird strikes on windshields and radomes, containment of failed blades in aircraft engines, and how to keep 50-year-old planes flying safely. The variety of things that we have had the opportunity to work on is certainly unique, especially in a university research environment.

Q: How has your work changed since you first started?

Bob: The most striking changes are in computer technology and accessibility. When I started here, we worked almost entirely with punched cards, magnetic tapes, and line printers. Every day around 4 p.m. the courier would collect everyone’s card decks, and drive them out to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to be run overnight. The line-printer output and your card deck would be delivered back to UDRI about 10 a.m. (unless the card deck fell in a mud puddle, which happened from time to time). If you made a typo and your program didn’t compile, or your data was wrong, you corrected your error(s) and turned in a new card deck that afternoon. (On the plus side, we recycled our line-printer paper, which is very dense, and bought pizza with the proceeds.) Rather than doing an instant Google or OhioLink search, we would make an appointment with the librarian to do a literature search, and provide a list of search terms on paper. Results would come back a week or two later, and then we could order any documents of interest, which would (usually) arrive in another couple of weeks. The copies we requested were Xeroxed by hand at distant libraries. I don’t miss any of this, besides the pizza.

Q: Why have you stayed with UDRI for so long?

Bob: I’ve always been lucky to work with great people here, and the work has always been interesting, so I’ve never really had a strong desire to go elsewhere. Secondly, I have had the opportunity to teach, mentor graduate students, and generally engage with the academic part of the University in addition to my research work, which would have been more difficult otherwise. The desire to guarantee a good and affordable college education for my three children certainly was a further incentive. As I’ve also said many times, only partly facetiously, I’m usually so far behind that no one would let me leave even if I wanted to.

May 4, 2023