The disturbing history of how conservatorships were used to exploit, swindle Native Americans

Pop singer Britney Spears’ quest to end the conservatorship that handed control over her finances and health care to her father demonstrates the double-edged sword of putting people under the legal care and control of another person.

A judge may at times deem it necessary to appoint a guardian or conservator to protect a vulnerable person from abuse and trickery by others, or to protect them from poor decision-making regarding their own health and safety. But when put into the hands of self-serving or otherwise unscrupulous conservators, however, it can lead to exploitation and abuse.

Celebrities like Spears may be particularly susceptible to exploitation due to their capacity for generating wealth, but they are far from the only people at risk. As a lawyer with decades of experience representing poor and marginalized people and a scholar of tribal and federal Indian law, I can attest to the way systemic inequalities within local legal practices may exacerbate these potentially exploitative situations, especially with respect to women and people of color.

Perhaps nowhere has the impact been so grave than with respect to Native Americans, who were put into a status of guardianship due to a system of federal and local policies developed in the early 1900s purportedly aimed at protecting Native Americans receiving allotted land from the government. Members of the Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma – Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations – were particularly impacted by these practices due to the discovery of oil and gas under their lands.

Swindled by ‘friendly white lawyers’

A conservatorship, or a related designation called a guardianship, takes away decision-making autonomy from a person, called a “ward.” Although the conservator is supposed to act in the interest of the ward, the system can be open to exploitation especially when vast sums of money are involved.

This was the case between 1908 and 1934, when guardianships became a vehicle for the swindling of Native communities out of their lands and royalties.

By that time, federal policy had forced the removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from eastern and southern locations in the United States to what is presently Oklahoma. Subsequent federal policy converted large tracts of tribally held land into individual allotments that could be transferred or sold without federal oversight – a move that fractured communal land. Land deemed to be “surplus to Indian needs” was sold off to white settlers or businesses, and Native allotment holders could likewise sell their plots after a 25-year trust period ended or otherwise have them taken through tax assessments and other administrative actions. Through this process Indian land holdings diminished from “138 million acres in 1887 to 48 million acres by 1934 when allotment ended,” according to the Indian Land Tenure Foundation.

During the 1920s, members of the Osage Nation and of the Five Civilized Tribes were deemed to be among the richest people per capita in the world due to the discovery of oil and gas underneath their lands.

However, this discovery turned them into the victims of predatory schemes that left many penniless or even dead.

Reflecting on this period in the 1973 book “One Hundred Million Acres,” Kirke Kickingbird, a lawyer and member of the Kiowa Tribe, and former Bureau of Indian Affairs special assistant Karen Ducheneaux wrote that members of the Osage Nation “began to disappear mysteriously.” On death, their estates were left “not to their families, but to their friendly white lawyers, who gathered to usher them into the Happy Hunting Ground,” Kickingbird and Ducheneaux added.

Lawyers and conservators stole lands and funds before death as well, by getting themselves appointed as guardians and conservators with full authority to spend their wards’ money or lease and sell their land.

Congress created the initial conditions for this widespread graft and abuse through the Act of May 27, 1908. That Act transferred jurisdiction over land, persons and property of Indian “minors and incompetents” from the Interior Department, to local county probate courts in Oklahoma. Related legislation also enabled the the Interior Department to put land in or out of trust protection based on its assessment of the competency of Native American allottees and their heirs.

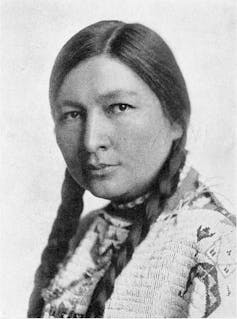

Unfettered by federal supervisory authority, local probate courts and attorneys seized the opportunity to use guardianships to steal Native Americans estates and lands. As described in 1924 by Zitkála-Šá, a prominent Native American activist commissioned by the Secretary of Interior to study the issue, “When oil is ‘struck’ on an Indian’s property, it is usually considered prima facie evidence that he is incompetent, and in the appointment of a guardian for him, his wishes in the matter are rarely considered.”

The county courts generally declared Native Americans incompetent to handle more than a very limited sum of money without any finding of mental incapacity. Zitkála-Šá’s report and Congressional testimony documented numerous examples of abuse. Breaches of trust were documented in which attorneys or others appointed conservators took money or lands from Nation members for their own businesses, personal expenses or investments. Others schemed with friends and business associates to deprive “wards.”

‘Plums to be distributed’

One such woman in Zitkála-Šá’s report was Munnie Bear, a “young, shrewd full-blood Creek woman … [who] ran a farm which she inherited from her aunt, her own allotment being leased.” Munnie saved enough money to buy a Ford truck and livestock for her farm, with savings remaining in a bank account. Once oil was discovered, however, the court appointed a guardian, who appointed a co-guardian and retained a lawyer, each of whom deducted monthly fees that depleted Bear’s funds. During the period of her guardianship, she was unable to spend any money or make any decisions about her farm or livestock, nor did she control her bank investment.

Zitkála-Šá’s report displays the extent of this practice:

“Many of the county courts are influenced by political considerations, and … Indian guardianships are the plums to be distributed to the faithful friends of the judges as a reward for their support at the polls. The principal business of these county courts is handling Indian estates. The judges are elected for a two-year term. That ‘extraordinary services’ in connection with the Indian estates are well paid for; one attorney, by order of the court, received $35,000 from a ward’s estate, and never appeared in court.”

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Wards were often kept below subsistence levels by their conservators while their funds and lands were depleted by the charging of excessive guardian and attorneys’ fees and administrative costs, along with actual abuse through graft, negligence and deception.

Reports like that of Zitkála-Šá’s resulted in Congress enacting the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. This put the Indian land that had not fallen into non-Indian hands during the federal policy of allotting plots back into tribal ownership and secured it in the trust of the United States. It also ended the potential for theft through guardianship.

But the lands and funds lost as a result of guardianships were not restored nor did descendants of those swindled ever enjoy the benefit of their relatives’ lands and monies either.

Andrea Seielstad is a professor of law at the University of Dayton.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.