Chris Harris’ campus visit became an extended stay

When my dad, Chris Harris ’55, was a high school basketball recruit from Floral Park, New York, in 1951, he was invited by Dayton Flyers star and fellow Long Island product Pete Boyle ’52 to visit UD and try out for the team.

Even though he was set to go to either St. John’s or Syracuse, Harris idolized Boyle — who was a local celebrity because of his exploits in the NIT — and couldn’t turn him down.

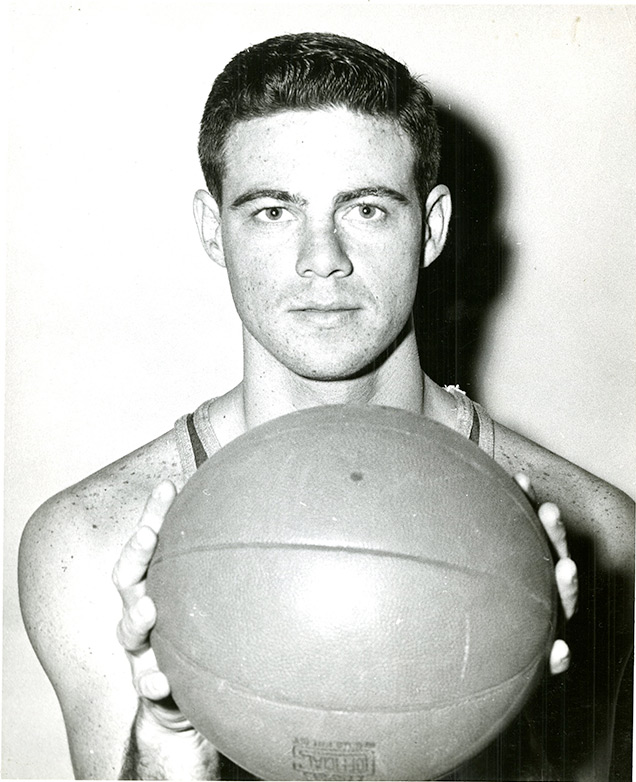

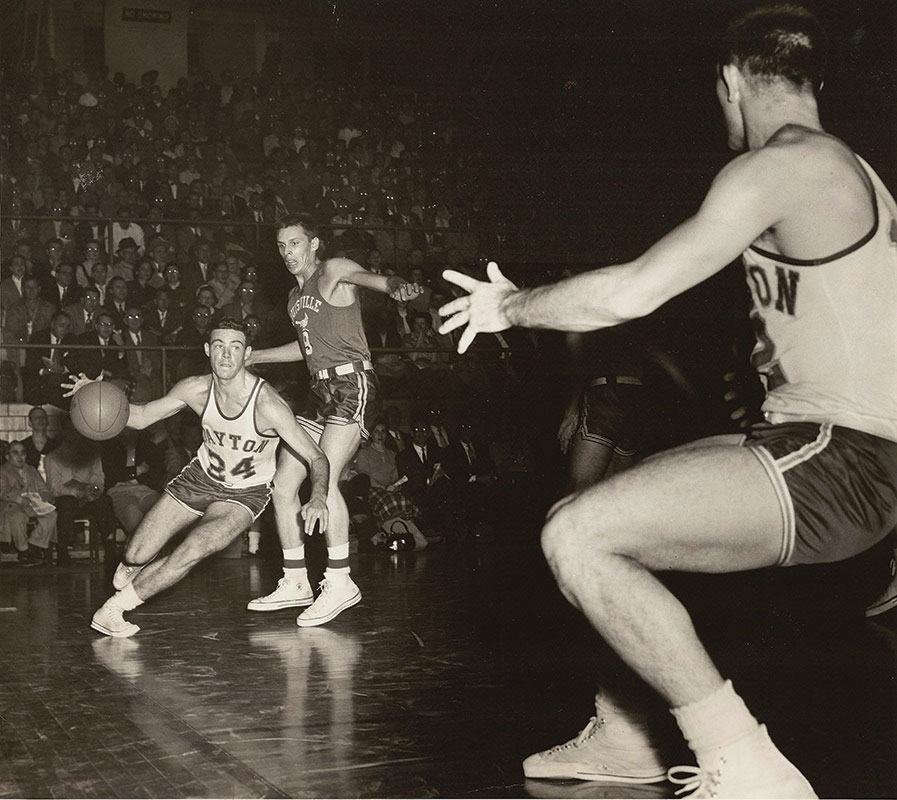

After an all-night train ride and playing on virtually no sleep, the 6-foot-2 guard impressed coach Tom Blackburn enough in the morning tryout to earn a scholarship. And the visit not only changed the course of his life but also took such a humorous twist that it became an oft-told story over the years.

“The first thing I remember about Chris was his visit to campus. It was an extended stay,” said a laughing Don Donoher ’54, a freshman on the team then who would become Blackburn’s successor.

“He came out and took to the whole atmosphere. It was supposed to be around a 48-hour visit, but he was having such a good time, he didn’t want to go home.”

Harris’ father worked on a passenger ship that traveled between his native England and the U.S., and his parents had moved to Bermuda that year, leaving Chris in the care of a friend’s family.

Let’s just say no one was really checking up on him.

“When Coach Blackburn said to me, ‘You’ve got a scholarship if you want it,’ I said, ‘OK, I’ll let you know.’ But I met some of the nicest guys,” Harris said. “Back then, the football and basketball players lived together at St. Joseph’s Hall. For example, on the second floor, there was (NFL Hall of Fame coach) Chuck Noll ’53 and Pete. We all got so close. We were like brothers.

“I just fell in love with Dayton. They’d take me out to places, and we’d have fun. I was supposed to go back to Floral Park on that Monday, but I didn’t want to go. They’d say, ‘Oh, you’ve got to stay a couple more days, we’ve got this thing we’re going to do.’

“I stayed almost two weeks. Finally, I ran into Blackburn, and he said, ‘Chris, you’re back so soon?’ I said, ‘Coach, I never went home.’”

Now 84 and living in Florida, Harris’ heart is still in Dayton — and for good reason. He had a Hall of Fame career at UD when the program was just becoming a national power. The city was abuzz about the Flyers, and players were treated like royalty.

He was a three-year starter and helped the team to an NIT runner-up finish as a senior, excelling as a defender, passer and floor general. That also helped him in 1955-56 to become the first English-born player to make the NBA.

“He was a popular Flyer. He was a likeable guy. And that helped him on the court, too, to have that type of personality. He was just a natural leader,” said Donoher of his eventual roommate.

While John Horan ’55 and Jack Sallee ’55 did most of the scoring, Harris always had the toughest backcourt assignment.

“He was very good at covering guards. He had a textbook stance, like a boxer’s stance. He could move his feet,” Donoher said. “He wasn’t lightning quick, but he could play up on an offensive player so tight. And he was the first Dayton player I remember who took charges. He was very clever at getting into position and taking a charge.”

Blackburn was known as a taskmaster, but the players never lacked for fun off the court — at least judging by their escapades. Harris was involved in a memorable adventure with Noll, who wasn’t yet the reserved and stoic leader he’d become playing with the Cleveland Browns and coaching the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Harris was suspended for a game at Baldwin-Wallace as a freshman for talking back to a professor, but he managed to see the Flyers play in Berea, Ohio, with the help of some football players.

“I was kind of down and wanted to be there. Chuck had the only car in the dorm — an old green jalopy we called the Green Hornet,” Harris said. “They asked if I wanted to go to the game, and I said sure.

“On the way home — back then there were no highways, you had to take back roads — the snow started coming down about an hour from Dayton. Chuck’s lights went out, and I said, ‘What are we going to do?’ They looked at each other, and he said, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do, round-baller: We’ve got a flashlight, and we’re going to put you on the hood and tie you up so you won’t fall. You stay on that hood and be our lights until we get back to the dorm.’

“I looked like a snowman, but we got back to the dorm.”

Before going off to the pros, Harris married local singing sensation Barbara Rettig, who was making national TV appearances then and was a weekly winner on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts (the American Idol of the 1950s).

He quit after one season in the pros, figuring he could make more money capitalizing on his Flyer fame in business. He planted roots in town, like most of the prominent players from that era, and eventually would have three TV-and-appliance stores. And he saturated the airwaves with commercials — with his wife singing the jingles.

He had a long stint as the radio voice of the Flyers with Bucky Bockhorn ’58.

He also became a Catholic while at UD, thanks largely to the influence of the devout Donoher. And all 10 of Harris’ children were born in Dayton — yes, that religious conversion may have had something to do with the large brood.

Though two of the sons have passed away, the other children have gone on to rewarding careers in part because of his example of hard work and perseverance. He has a tinge of regret, though, for how much his obligations took him away from home.

“I’m very proud of the kids, but I can’t take the credit. Barb was the one. She gave her career up for the family,” he said.

He did his part, too, as I well know.

Since he was a Flyer and so well-known in the community, the rest of us aimed high. My younger brother, Ted, and I followed his path by getting scholarships to Dayton. I joke that I spent my career passing the ball to Jim Paxson ’79, while Ted played on the 1984 Elite Eight team with Roosevelt Chapman ’91.

We probably wouldn’t have gotten there without good genes and a decision my father made when I was in sixth grade, which he retold recently:

“When we moved to Far Hills Avenue (in Kettering, Ohio), we put in that full basketball court in the backyard. We even had lights,” my dad said. “I remember Barb coming up to me and saying, ‘How much did that cost?’ I said, ‘It was $16,000, but don’t worry about it. You’re going to be proud of your boys.’”

My parents also taught us about equality and diversity through their actions. Ted and I made African-American friends while at UD and would bring them home for meals, and they were embraced, literally and figuratively, in the Harris home.

Among them was Terry Ross ’78, a 6-foot-9 center from Indiana.

“They became my second family,” Ross said.

Terry and I lived together for a few years after college, and he was a fixture at Sunday cookouts.

“I’ve never had anyone do more for me than the Harris family,” Ross said. “Chris would be at the top of my list for people I admire and people who touched my life in a positive way.”

My dad also laid a foundation of faith in each of us. That’s not something he had growing up. But he became intrigued by Catholicism because Donoher exhibited an internal strength that was attractive to others, my dad said.

“We were like the Odd Couple. [Donoher] was really a straight shooter. Everyone loved him. He’d go to daily Mass, and he was just a classy guy. I was the complete opposite, but we hit it off,” Harris said.

“We were playing at Toledo and roomed at the hotel. I just started thinking about my life. I said [to Donoher], ‘Tell me about this Catholicism.’ It was 11 at night, and we talked to 4 or 5 in the morning. By the time we got through, I said, ‘I’m going to go back home and tell my parents I want to become a Catholic.’

“Not to sound hokey, but I always used to think, ‘Boy, I’d love to find someone I could marry.’ The night I was baptized, Jack Boesch — of Boesch Lounge at UD Arena — said, ‘There’s a singer at the Van Cleve Hotel downtown. We’re going to go see her. Do you want to go?’ I said, yeah, sure. I went down there and met my future wife.”

They’ve been married for 63 years, but that certainly wasn’t the only lasting relationship to come from his UD years.

The players he first met on that prolonged visit — who showed him warmth and acceptance along with a good time — turned out to be lifelong friends.

“Going to Dayton saved me,” my dad said. “If I had stayed in New York — I was a wild kid. I didn’t know that’s how people were. They were all so great. They were just wonderful.”