Pietà of Mark Balma

Pietà of Mark Balma

The Pietà Revisited?

– Father Johann G. Roten, S.M.

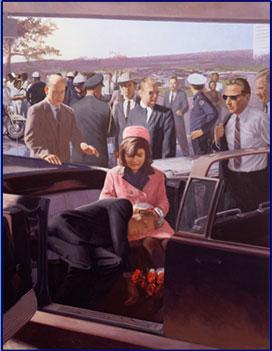

Mark Balma’s rendering of John F. Kennedy’s dying moments is of a highly emotional quality. It captures a moment of intense personal drama showing the grief-stricken Jacqueline Kennedy cradling the mortally wounded president in her lap. However, the five-by-seven-foot oil tempera painting transcends private tragedy. It signals shattered expectations and the end of high hopes for a whole nation. All of a sudden the myth of Camelot bends and is twisted in the fateful but far more real script of Greek tragedy. And then there is a third level of emotional impact this work of art conveys and effects. It throws the onlooker in a maelstrom of nostalgia and fatalism. All those beautiful sentiments of what could have been but never was, keep rushing back to haunt a nation confronted with still another, a potential catastrophe of war.

The question is whether Balma’s painting qualifies as Pietà? The motif of the Pietà, imago Beatae Virginis de pietate (M. Franciscus de Insulis, 15c) or tristis imago Beatae Virginis (~1404),and Maria Addolorata (1414/15) has no immediate scriptural basis other than the reference to Mary’s presence at the foot of the Cross (Jn 19:25-27). Bonaventure and others attributed the theme of the Pietà to popular piety (ut pie creditur, Office of the Passion, 13c.) The origin of the pictorial motif seems to be a matter of speculation. Not so the literary origin of this theme. It is related to the well known and cross-cultural literary topic of the mother’s yearning and grief for her dead son. In Christian tradition it becomes Mary’s desire to hold and embrace her crucified Son alluded at in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus (~8/9c). With Gregory of Nicomedia (9c) and Simeon Metaphrastes (10c) the theme evolves and describes the fulfillment of the mother’s desire; she, Mary, now holds and embraces her Son. Later, the intimacy with the crucified and dead Jesus will expand and include the whole of humanity as can be seen in the Planctus ante nescia (~ 1150). Literary sources of the 12/13c (for example, the so-called Anselm dialogue, and the well known Meditationes Vitae Christi) lend this spiritual desire to embrace and hold her dead Son an even more down-to-earth and visual expression: Mary now holds and cradles Jesus’ head in her lap, and eventually the whole body (Mechthild of Hackeborn, 13c). With the 15c the theme is fully developed.

The significance of the Pietà is closely related to medieval spirituality, in particular the imitation of Jesus Christ. All are called to imitate the life and teaching of Jesus Christ. Indeed, whoever imitates his life understands and lives his message. The way to insight and implementation begins with meditation. In the scene of the Pietà, Mary shows how important it is for the faithful to meditate Christ's passion. Mary is the model of meditation, and by the same token a visual and dramatic invitation to compassion. In the Pietà the various stands of Christ's Passion come together and are immediately present, visually present to the spectator. All of the stations of the cross are summarized in the dead body of Jesus. Mary's presence is not only that of the grieving mother, desolate over the loss of her Son. The cradling and embracing of the body, well known and telling symbols of the unio mystica (Henry Suso, Eternal Wisdom, chapter 19), highlight her own passion, her own suffering, which is indeed com-passion, the highest of human identification with the salvific passion of Christ. For the faithful and “compassionate” onlooker - meditating on the significance of so much pain - there is the additional meaning of his or her own responsibility in Christ's death, and of the pride of humanity's salvation. This compassion becomes part of the authentic imitation of Christ. Mary plays a mediating role in this process. She is the bride (Canticle of Canticles 1:12) intimately sharing Christ's Passion. She is also a symbol of the Church, “the future mother of life eternal,” and of the individual soul grieving both Christ's and our own death as sinner.

The actual representation of the Pietà, which as mentioned has the value of a synthesis of crucifixion, deposition, planctus and entombment is known since the 14 c, and has been of the most telling staurological symbols ever since.

1. Early representations (14c) follow a naturalistic pattern. Christ's body is featured in a “stairway”-position to suggest maiming and brokenness. Mary is pictured in a vertical and upright position; she is the grieving mother, compassionate but impassible. Some of the more prominent examples can be found in Wetzlar, Erfurt, Scheuerfeld and Salmdorf (Germany).

2. Around 1350, the naturalist rendering of the Pietà gives way to a more symbolic approach. Inspired by a mystical interpretation of the Pietà and increasing of Marian devotion the central focus of the message is now that of the Addolorata meditating her own life trajectory from Bethlehem to Calvary. As a consequence, the body of the Savior is featured in diminutive shape, that of a child. Thus, his mission from Incarnation to Redemption is symbolized in a global manner. This second type of the Pietà seems to reflect the Suabian tradition (Rhineland, Radolfszell) and its love of the diminutive form.

3. The next stage, also called soft style, appears before and around 1400. The Pietà is of courtly origin and goes by the name of Schöne Vesperbilder or beautiful Pietàs. The distinctive mark is Christ's almost horizontal position on Mary's lap. The overall triangular and proportionate form elicits an impression of balance, elegance, of solemn silence and harmony. Mary is featured as a young and aristocratic woman, composed in her meditation of the dead body of her Son. Figures of this period are crafted in stone, terra cotta and alabaster, rarely in wood. The origin points to Bohemia and Austria.

4. The soft style makes place to a more rustic type at about the same period. In contrast to the previous aristocratic style, the Pietà of this type finds its origin in a more bourgeois milieu and in rural regions. The realism of the representation shows for example, in the aged and grief-stricken Mary. The distinctive characteristic of this Pietà lies in the unusual position of Christ's dead body. In order to attract the attention of the onlooker to the Savior, his body is presented in frontal posture. It is turned, almost twisted looking, towards the spectator. Indeed, the torn and bloody body of Jesus is presented to the meditation of the faithful. Positioned mainly horizontally, it forms with the figure of Mary a compact triangle with the exception of Christ's head. The latter literally protrudes or sticks out from the overall composition, and thus captures the attention and intensifies sentiments of grief and compassion. The Burgundy tradition is mentioned for its possible origin.

5. Around 1450 a new and what we might call the classical type of the Pietà emerges. Its distinctive features are the strict triangular composition and the diagonal position of Christ's body. It is believed that this type finds its origin in the Netherlands and was influenced by the paintings of Rogier and Dirk Bouts. The lower Rhine regions in general are home to the diagonal type of the Pietà.

6. A further development in the sixteenth century shows the Pietà with the body of Christ at Mary's feet. The body is literally poured out in front of Mary's knees with Christ's head, sometimes also the upper part of the body, in her lap. This type is particularly commensurate with baroque culture, its love for drama and display of great emotions, the celebration of tragedy and incarnational realism.

7. A somewhat a-typical Pietà, influenced by the Renaissance paintings of the deposition, among other sources, shows Jesus and Mary in upright position, both standing, as can be seen in Michelangelo's Pieta Rondanini (1540-64). This composition expresses the intensity of intimacy and union between Mother and Son: Jesus' body is literally hanging (sometimes hovering) in the arms of the Mother who, in turn, holds on to her Son as if seeking comfort and support.

The various types presented here are not an exhaustive presentation of the history of this iconographic motif. They show stages in development, typical representations, and their spiritual significance. However, the Pietà did not disappear with the end of the baroque period. The Pietà may have been one of the most representative Marian motifs of the twentieth century, not in the least due to two world wars. In fact we find in Western Europe countless representations of the Pietà on marketplaces and in cemeteries. They serve as war memorials commemorating the fallen soldiers of a village, region, or nation. It may further be said that the Pietà is not really a Pietà. The dead body of Christ is replaced by that of a soldier, and in place of Mary we find a feminine figure symbolizing Germania (Germany) or Marianne (France), meaning the respective fatherland or nation. There is a rarely perceived and underlying irony presented with these war memorials. The mother who cradles the dead soldier is not only the one who mourns but also the one who sent the dead soldiers into battle, thus emphasizing the cruel ambiguity of war. It is this derivative concept of the Pietà that comes closest to Balma's attempt to stylize the Kennedy couple as Pietà.

We asked the question if Balma's painting qualifies as Pietà. For the artist, his Pietà is a “moment imbued with spirituality.” What Balma seems to mean by spirituality are “certain graces given to deal with tragedy.” This applies most certainly also to the Pietà. There is a special grace in love embracing pain; in pain cradled in the arms of love. However, does Balma's Pietà have and offer redeeming grace? There is a difference between senseless suffering and redeeming suffering. Balma's Pietà is a typical example of the tragedy of senseless suffering: senseless as to intent and consequences. The Pietà as we know it invites to meditation on our personal salvation. Balma's artwork has initiatory value and as such raises the question about a way to transcend senseless suffering, about the possibility of redeeming suffering. However, Balma's message remains incomplete and possibly misleading. There is first a question of form that may be misleading. John and Jackie Kennedy are part of American lore and history, thus too well known and defined to be easily transposed to the realm of iconographical expression and representation. The power of absorption of these two personalities is too strong, especially in the American context, to allow for a religious redefinition of the Kennedy assassination. The comparison between Balma's Pietà and the traditional Pietà remains purely external, a matter of posture and position. Another point of form concerns the contrast Mother-Son (traditional Pietà) and husband-wife (Balma's Pietà). The former immediately relates to the life as given, life as received and to be given anew. The tendency here is one of passing on life, of sharing it. On the other hand, the relation husband-wife remains, in this particular situation, more self-contained and reciprocal, one of personal love.

In short, Balma's figuring of the Pietà needs to lead to the spiritual significance of the traditional Pietà in order to be credible. There is legitimate doubt that it achieves the goal. The degree of “secularization,” the distance between form and content, is too far advanced to reconnect with the fundamental message of the Pietà which is to foster union with the suffering Christ, recognition of our need of salvation, and the meditation and praise of redeeming love and suffering.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.