Fountains in Annunciation Art

Mary and Fountains in Art

– Sister M. Danielle Peters

The significance of water, especially that of the spring with healing water, is a very effective image for the tangible presence of God among His people.

The Virgin and Child with Angels by a Fountain, Bernaert Van Orley (1492-1541)

The Virgin and Child with Angels by a Fountain, Bernaert Van Orley (1492-1541)

There are basically two traditions of the Annunciation iconography: one situating it at a cistern or fountain, the other favoring the interior of a house. Both are influenced by the apocryphal gospels. In this view, the fountain at the Annunciation scene of the apocryphal writings of St. James has a profound meaning. It can be a sign of Christ’s Incarnation in Mary’s womb.1 To this day, the Greek Orthodox Christians venerate a wellspring of Nazareth where the Annunciation might have taken place.2 Since the Middle Ages, Western representations of the Annunciation normally placed the event indoors: in a bedroom or private chamber, where the Virgin – usually at prayer – finds herself surprised by the angel.

About the year 1400, however, a new version of the Annunciation scene suddenly appeared in European paintings, which portrays Mary at the moment of the Annunciation in a richly flowering garden. The garden is walled (hortus conclusus) and objects, which might include a small hexagonal fountain and an open spring or well, often surround Mary. The origin of many of these symbols is biblical; for example, the enclosed garden and the sealed fountain in its midst are taken from the Song of Songs.3 The oldest example of a western representation of the Annunciation with Mary kneeling next to a source and with a pitcher or amphora in her hand is dated back to the seventh century (Milano, ivory cover).

The Byzantine mosaic portraying the Annunciation at the well of San Marco in Venice from the 1220 AD4 shows Mary fetching water as the Angel of the Lord approached her. Again, we can interpret this scene in terms of Mary being the channel or aqueduct to bring the fountain of life giving waters to this earth, At the same time, the scene of Mary holding an empty pitcher can also remind us of the wedding at Cana where Mary tells the servants, or us, ‘Do whatever He tells you!’

The first known Marian painting to use garden symbols is not an Annunciation scene but a Mother-Child representation (see image on the right) probably dating from the beginning of the fifteenth century.5 Mary is crowned with ‘Lauda Maria’ inscribed in her halo. Around her we see the city gates, the ark, the rod of Aaron, the burning bush, the fountain, the fleece, the rose, the closed door reminding us of the Song of Songs.

The earliest iconographic use of the images of the Song 4:12, with Mary and her Son, is on the painted parchment cover of a thirteenth century Psalter now in the library of the government in Bamberg, Germany. The Madonna with child is enthroned on a rainbow and surrounded by four hallowed heads and by four larger typological figures: Aaron with his rod, Jesse with his root, Ezekiel pointing to the closed gate and in the lower right Solomon pointing to a fountain. At least from the beginning of the thirteenth century, we often find Mary either as Virgin at the Annunciation or as the Mother with child encircled by emblems referring to biblical themes. However, the enclosed garden and the sealed fountain do play a minor role in Marian iconography before the fourteenth century. The Wyscherad Codex, for instance, from the eleventh century shows the Nativity scene with emblems of the burning bush, Aaron’s blooming rod and Ezekiel’s closed gate; but no garden or fountain.6

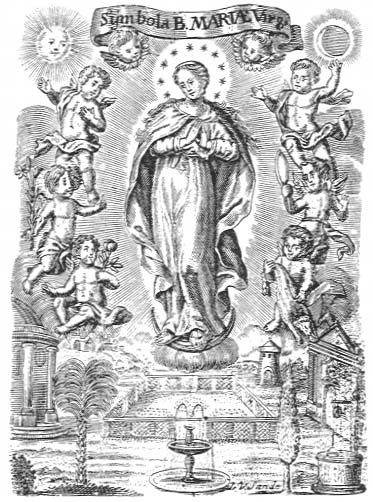

At the beginning of the sixteenth century the images of Mary surrounded by symbols as the fountain is now applied to Mary as the Immaculate Conception. Devotional pictures of the Immaculate Conception surround Our Lady with symbols attributed to her purity.7 In the center on the bottom we see an overflowing fountain (fons ortorum) watering an olive tree (Olivia speciosa) to its left. On the right bottom we see a well (puteus aquarum viventium) and in the background the outline of the Holy City, Jerusalem. All of this is shown in a setting of a closed garden (hortus conclusus).8

A similar portrayal is found in the Manual of the Arch confraternity dedicated to the Immaculate Conception with the fons signatus to her left.9

In the paintings of Mount Athos, Mary is depicted as life-giving spring. On a tapestry in the Louvre, Mary and her child are shown in the hortus conclusus next to a fountain. On the left Moses is seen as he makes his way through the Red Sea and on the opposite side the lame at the pond of Bethesda.

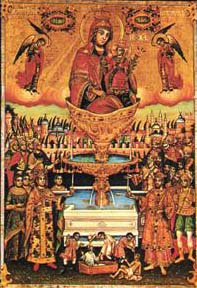

The icon of Life giving Fountain is well known in Eastern Christianity.10 It is not only related to the phenomenon of the fifth century but also to Mary’s maternity and her role for God’s children. The icon shows Mary as receiver of God’s Life who then distributes these waters of both spiritual and physical healing to humanity. As such Mary is depicted here as Mediatrix, Intercessor and even Co-Redemptrix.

Our survey of Mary as Fountain or Well in art offers a rich documentation of biblical as well as doctrinal reflections on Mary’s person and role in salvation history. Images of Mary without child in connection with the well point to her emptiness of self and readiness to be filled with the waters of salvation as at the Annunciation. They also show her interwovenness with symbols of the Old Testament foreshadowing her predilection as sealed fountain in the garden of delight. They reveal Mary’s virginal surrender to the waters that will flow from her and tacitly to her sinlessness as well. Mary with Child and fountain point to her divine and inclusively also to her spiritual maternity.

[1] Compare: E. Gössmann, Die Verkündigung an Maria im Dogmatischen Verständnis des Mittelalters, Max Huber Munich, 1957, p. 29.

[2] Compare: M. J. Lagrange, Evangile selon Saint Luc, Paris, 1921, p. 28.

[3] See: Brian E. Daley, The “closed Garden” and the “Sealed Fountain”: Song of Songs 4:12 in the Late Medieval Iconography of Mary. In: Medieval Gardens, Dumberton Oaks Research Library, Washington DC 1986.

[4] See: Wolfgang Braunfels, Die Verkündigung, Düsseldorf 1949, image 4.

[5] Alfred Stange, Deutsche Malerei der Gotik, Berlin 1938, III.37.

[6] Henrik Cornell, Biblia pauperum, 1925, 125.

[7] The image to the left is entitled ‘Symbol of Mary’ from the 17th century.

[8] Stefan Geissel, Geschichte der Verehrung Marias im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert. Ein Beitrag zur Religionswissenschaft und Kunstgeschichte. Herder Verlag Freiburg im Breisgau 1910, p. 250.

[9] Manuale Archiconfraternitas. Sub titulo: Immaculatae Conceptionis Deiparae Virginis Mariae.Vienna Austria 1642.

[10] The font, fountain or basin is pictured as two basins, one in another. The font in which we see Mary with her Son is the ‘source,’ God who is Life. The waters flowing from the basins are collected in a pool for healing. People of all stages of life come to the water. In later traditions, the fish seen swimming in the pool relate to a legendary story of fish jumping from a frying pan to the pool, and the deeper mystical meaning of fish as the faithful seeking life. See: Virginia Kimball, Theotokos of the Life Giving Fountain, STL thesis, 2000, 158.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.