Mary in Miniature: Books of Hours in the Marian Library Collection

Mary in Miniature: Books of Hours in the Marian Library Collection

Introduction

Introduction

From 1250 to 1550, Books of Hours, or horae, were the best-selling book in medieval Europe. These private prayer books were specifically designed for laypeople and centered on a series of prayers known as the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Several factors led to the emergence of Books of Hours as the most coveted books in medieval Europe. Such a prayer book satisfied the medieval desire to imitate the clergy, allowing the reader to pray all 150 psalms. As what is known as “the cult of the Blessed Virgin” developed, particularly in the later Middle Ages, Books of Hours played on the medieval desire to pray to Mary and emulate her qualities. Among the distinct features of horae are their images. Known as miniatures, they served as wayfinding tools, inspiration for prayer, aids to contemplation, and access for the marginally literate.

Books of Hours are a window into medieval society, Marian devotion, and book history in the later Middle Ages. This online exhibit features digitized medieval Books of Hours and individual leaves, dating from circa 1440 through the early 16th century, from the Marian Library’s collection. Also featured is an early 16th century manuscript on loan from the collection of Stuart and Mimi Rose.

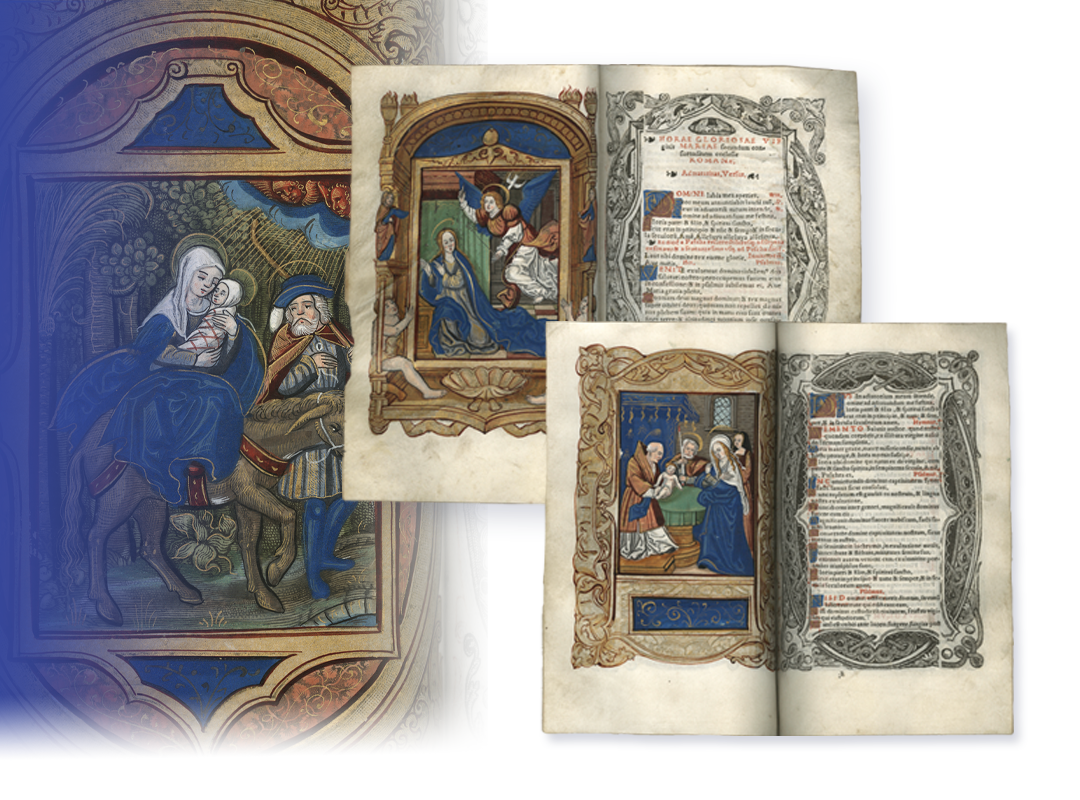

Annunciation and Presentation Leaves

These miniatures depict the Annunciation and the Presentation, and both date to approximately the middle of the 15th century. The Hours of the Virgin were illustrated with scenes from the infancy cycle. The Annunciation — when the angel Gabriel announced to Mary that she was to be the mother of God — was the typical illustration for the hour of matins, usually prayed at about 2 a.m. The Presentation — Mary presenting Jesus in the temple — was the typical illustration for the hour of none (Latin for ninth), the midafternoon prayer.

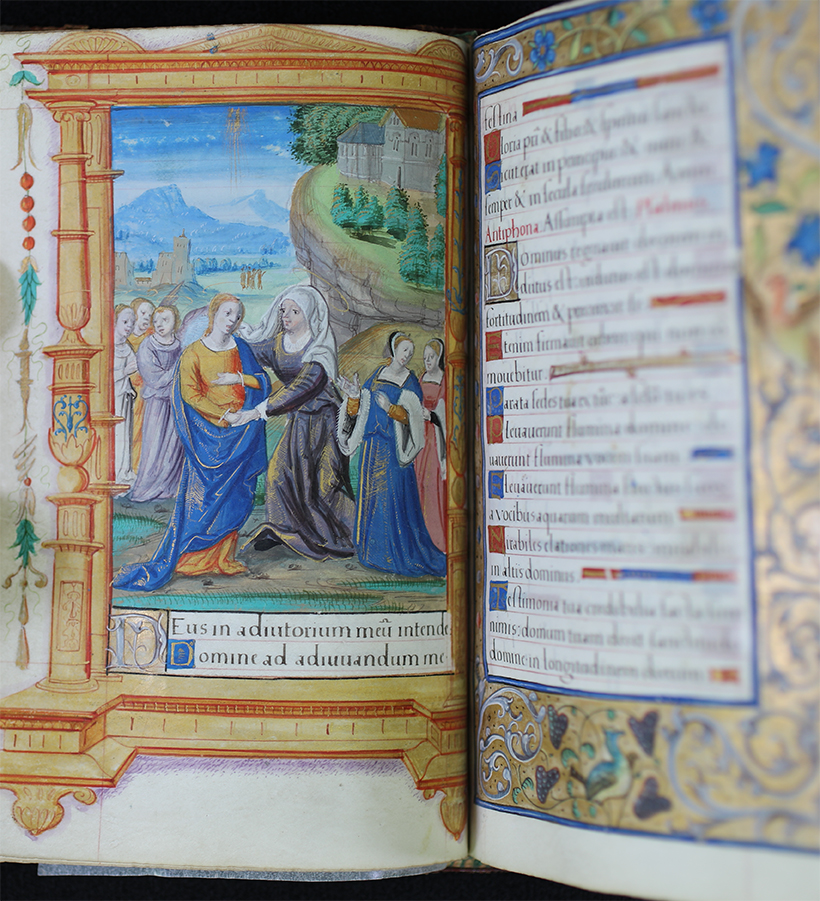

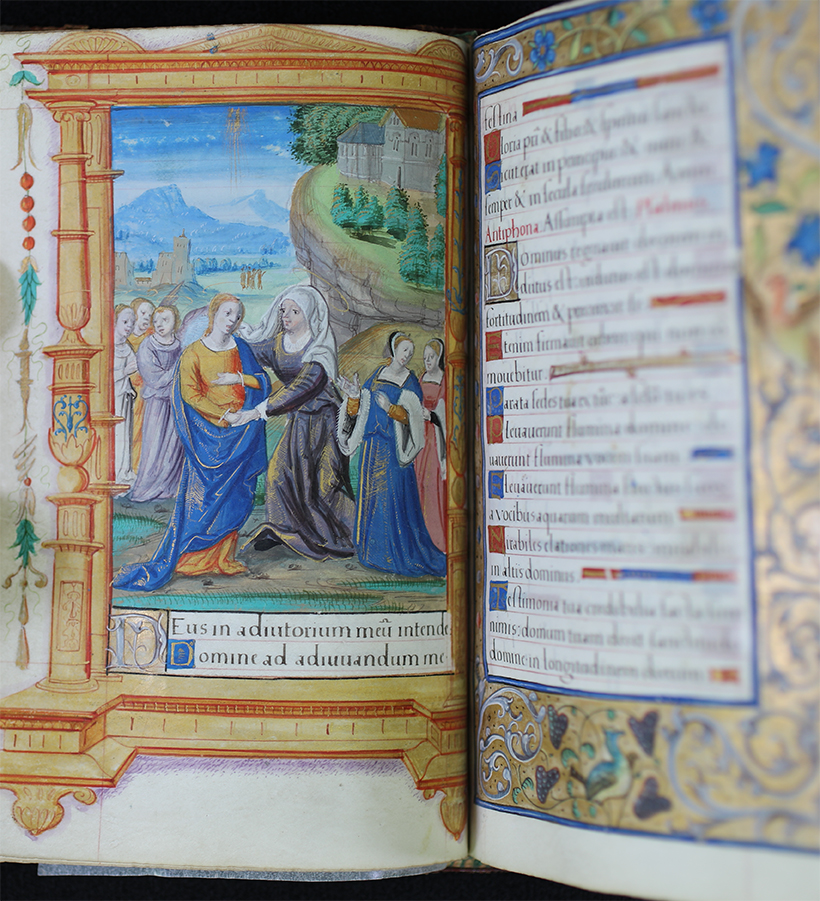

Book of Hours for use of Rouen

This image is the opening for the hour of lauds, a prayer typically said at dawn, and depicts the Visitation. The Visitation is described in the Gospel according to Luke (1:39–56). When pregnant with the infant Jesus, Mary visited her cousin Elizabeth. Upon Mary’s greeting, the pregnant Elizabeth felt the infant St. John the Baptist leap in her womb.

Books of Hours frequently included portraits of their owners and their patrons and loved ones. This image contains a portrait of what were probably the owner’s two daughters (located to the right of the Virgin Mary and Elizabeth).

This book, made for use of Rouen, France, circa 1520–1530, features 14 full-page, hand-painted miniatures.

Book of Hours for use of Rouen, France

Latin and French; Illustrated by the Master of the Ango Hours; 1520–1530; Rouen, France; From the collection of Stuart and Mimi Rose

Book of Hours for use of Rouen, France

Latin and French; Illustrated by the Master of the Ango Hours; 1520–1530; Rouen, France; From the collection of Stuart and Mimi Rose

Hours of the Virgin

The heart of every Book of Hours is a series of prayers called the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or, the Hours of the Virgin. The paintings in Books of Hours, called miniatures, often featured work by the best artists of the time. Miniatures in the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary illustrate events in Mary’s life surrounding the infancy of Christ. They typically follow a standard cycle:

The heart of every Book of Hours is a series of prayers called the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or, the Hours of the Virgin. The paintings in Books of Hours, called miniatures, often featured work by the best artists of the time. Miniatures in the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary illustrate events in Mary’s life surrounding the infancy of Christ. They typically follow a standard cycle:

Hour | Image

Matins | Annunciation

Lauds | Visitation

Prime | Nativity

Terce | Annunciation to the Shepherds

Sext | Adoration of the Magi

None | Presentation in the Temple

Vespers | Flight to Egypt

Compline | Coronation of the Virgin

Book of Hours for use of Rome

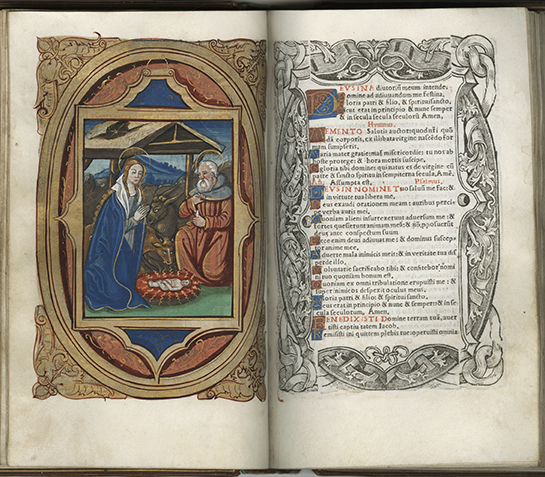

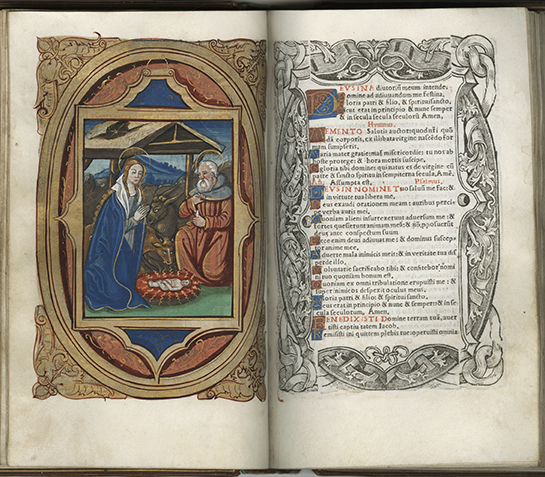

This page depicts the hour of prime and includes an image of the Nativity. The iconography is based on the visions of the 14th century mystic St. Bridget of Sweden. In her visions, St. Bridget described a glowing Infant Jesus on the ground surrounded by Mary, with long, blond curls, and Joseph kneeling in adoration.

Book of Hours for use of Rome, hour of prime | Nativity

Latin and Greek; Published by Pierre Vidoué; Paris, 1523; Gift of Stuart and Mimi Rose (2015)

Book of Hours for use of Rome, hour of prime | Nativity

Latin and Greek; Published by Pierre Vidoué; Paris, 1523; Gift of Stuart and Mimi Rose (2015)

Timeline

Circa 30–48: Apostles pray and recite psalms and scripture at the third, sixth, and ninth hours of the Roman day following Jewish tradition (Acts 3:1).

Circa 30–48: Apostles pray and recite psalms and scripture at the third, sixth, and ninth hours of the Roman day following Jewish tradition (Acts 3:1).

516: St. Benedict of Nursia establishes the Divine Office, a cycle of psalms and prayers recited in daily monastic life.

1096: Pope Urban II declares the daily recitation of the Little Office of the Virgin obligatory for clergy.

Circa 1250: The Little Office of the Virgin becomes the basis for the first Books of Hours produced for European nobility.

1430: The Duke and Duchess of Bedford give what is now known as the Bedford Hours to Henry VI of England.

Circa 1450: Johannes Gutenberg introduces movable type and the printing press in Mainz, Germany.

Circa 1455–1480: Black Books of Hours (also known as Black Hours) are produced in Flanders for members of the Burgundian court, with silver and gold text inscribed on vellum dyed with corrosive iron gall ink.

Circa 1480–1500: Manuscript Latin Book of Hours on display is produced.

1489: Antoine Verard begins using illustrations modeled on Phillipe Pigouchet’s work for the woodblock illustrations in his printed Books of Hours.

Circa 1500: Miniature unfinished manuscript on display is produced.

Circa 1520–1530: Master of the Ango Hours paints the Book of Hours for the use of Rouen.

1522: Thielman Kerver dies; his widow, Yolande Bonhomme, takes over his Paris print shop, printing the Dutch Book of Hours 11 years later (1533).

1545: Following the Council of Trent, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary becomes an obligation only on Saturdays.

Books of Hours and Book History

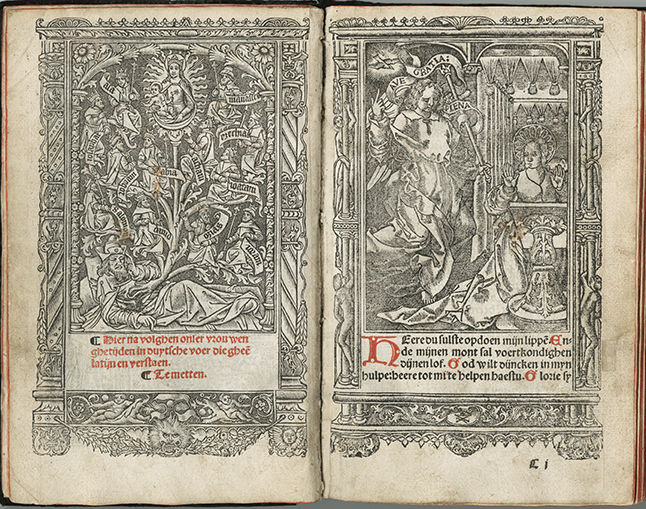

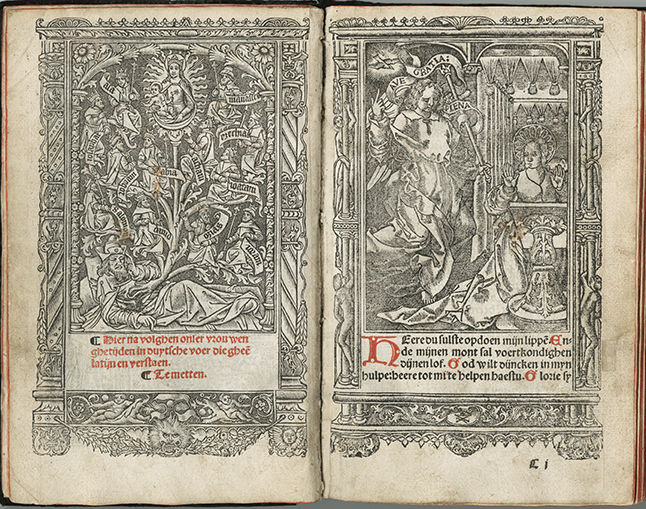

Tree of Jesse and Annunciation miniatures in a printed Dutch Book of Hours [Die Ghetiiden van onser liever Vrouwen...], published by Yolande Bonhomme, the widow of Theilman Kerver. Paris, 1533.

Tree of Jesse and Annunciation miniatures in a printed Dutch Book of Hours [Die Ghetiiden van onser liever Vrouwen...], published by Yolande Bonhomme, the widow of Theilman Kerver. Paris, 1533.

Books of Hours remained popular even as the printing press revolutionized Europe in the 15th century. The transition from manuscript production to the printing press was not always straightforward. Just as the first movable type in Europe was modeled on contemporary handwriting, conventions like hand-illuminated gold initials, vellum pages, and custom miniatures reassured owners that although the production methods had changed, a printed Book of Hours was still a treasure.

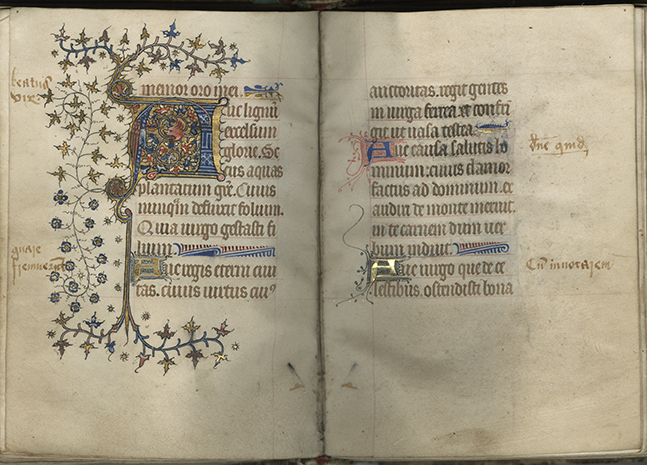

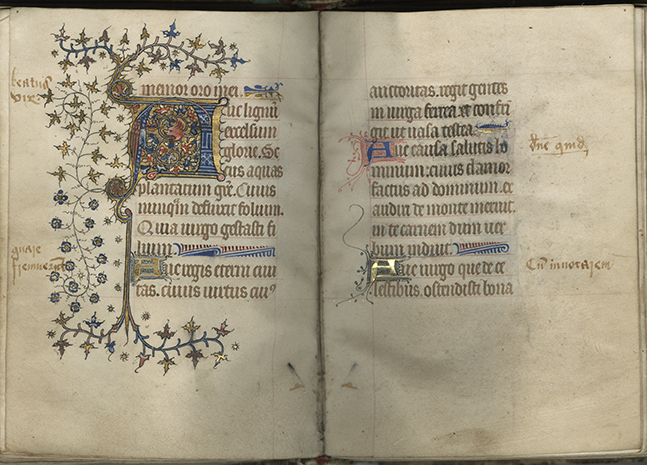

An initial A indicates the beginning of the Marian hymn “Ave lignum excelsum gloriae” in a manuscript Latin Book of Hours, circa 1480–1500.

An initial A indicates the beginning of the Marian hymn “Ave lignum excelsum gloriae” in a manuscript Latin Book of Hours, circa 1480–1500.

Manuscript Books of Hours could be highly customized to include devotions to local saints or patrons of the owner, and manuscripts like the one above did not cease being produced with the advent of printing. Still, many conventions applied, such as the illustrated scenes accompanying the texts for certain canonical hours and the inclusion of a calendar, a litany of saints, Gospel lessons, an Office of the Dead, and popular prayers and psalms. Illustrated scenes of Christ’s birth and passion reminded readers of the cycle of redemption and the biblical origins of the texts as they prayed the hours; they also helped readers find their place before page numbering became common.

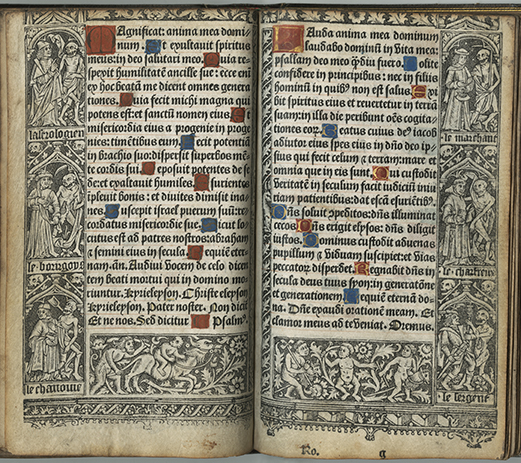

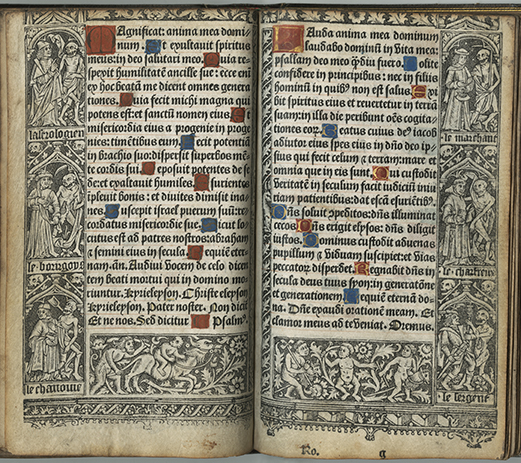

The Magnificat in a printed French Book of Hours for use of Rouen [Heures a l'usage de Rouen], published by Antoine Verard. Paris, 1503.

The Magnificat in a printed French Book of Hours for use of Rouen [Heures a l'usage de Rouen], published by Antoine Verard. Paris, 1503.

In lieu of the ornate illumination that decorated earlier manuscript Books of Hours, printers such as Antoine Verard used wood and metal cut in relief to produce full-page illustrations and elaborate borders. The amount of labor involved meant that images were reused and sometimes clashed with the text. Although seeing the Magnificat surrounded by memento mori illustrations may seem strange today, it would likely have been less dissonant for medieval and early modern readers.

Marian Prayers

The Obsecro te and the O intemerata are two Marian prayers frequently included in Books of Hours. Obsecro te is an expressive prayer that allowed devotees to experience an intimate relationship with the Mother of God. The prayer lists Mary’s qualities, reminds her of the joyful role she played in the Incarnation, describes the sorrows and her role in Christ’s passion, and petitions her. The prayer ends with its most moving request:

The Obsecro te and the O intemerata are two Marian prayers frequently included in Books of Hours. Obsecro te is an expressive prayer that allowed devotees to experience an intimate relationship with the Mother of God. The prayer lists Mary’s qualities, reminds her of the joyful role she played in the Incarnation, describes the sorrows and her role in Christ’s passion, and petitions her. The prayer ends with its most moving request:

And at the end of my life show me your face, and reveal to me the day and hour of my death. Please hear and receive this humble prayer and grant me eternal life. Listen and hear me, Mary, sweetest virgin, Mother of God and mercy. Amen.

The O intemerata is similar in tone and structure but calls on both the Virgin Mary and St. John. This prayer requests them “to be, at every hour and every moment of my life, inside and outside me, my steadfast guardians and pious intercessors before God …, for you can obtain whatever you ask from God without delay.”

Have you ever wondered what the bestseller list might have looked like 500 years ago? Any guesses?

Read more

Ever wondered what the Nativity looked like to Medieval eyes? Why is Mary always on the left (... and frequently blond)? And what does Bridget of Sweden have to do with it?

Read more

Books of Hours were owned and read by many medieval Europeans. What did it really take to own and use one of these exclusive editions in the 14th and 15th centuries?

Read moreCurator, Jillian Ewalt

Co-curator, Henry Handley

Contributors, Sarah Cahalan and Melanie Zebrowski

Digitization and Photography, Ryan O'Grady

Graphic Design, Ann Zlotnik

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.