Benjamin Miller, Prints of

The Prints of Benjamin Miller

– Father Johann Roten, S.M.

Benjamin Miller had not always been a print artist. There was a time when students and admirers of his paintings were raving about the delicate opulent interiors, the fascinating blues, and the strange mystic greens. It was around 1921, after his return from Paris, that Miller became aware of the unusual depth of emotions evoked by the use of vibrant black and white. It is the time when he begins to resonate with Odilon Redon’s “Black is the most essential of all colors. ...It is an agent of the mind far more than the beautiful colors of the palette or the prism.”

Miller discovers and exploits with a singular maestria the possibilities offered by woodblock. He will be best remembered for his woodcut prints. Starting with the 56 silhouette drawings for the Duveneck Society (1924) and ending with Abstractions I and II (1935), his woodcuts will be considered too modern, too radical in the beginning. By 1927, his Flight into Egypt is acclaimed in the New York Times as the work of a young artist “who is using modern design in support of traditional religious features.” His most famous work, The City (1928), earns him the title “American Expressionist,” and beginning in 1929, his work receives acclamation in the United States and in Europe.

Miller was born and raised in Cincinnati. He received a BA in electrical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1901, but returned to Cincinnati to pursue a career in art. At the Cincinnati Art Academy, he met Ella G. McCullough, a fellow art student,whom he married in 1914 and then lost to spinal meningitis in 1918. Years of travel to England, Holland, France, and Italy will follow, and with it the exposure to early expressionism and some of its representatives like Gauguin, van Gogh, Matisse, Nolde, and Rohlfs. Miller’s woodcut prints are marked by these encounters, but their influence remains subordinate to the strong individuality of his person and artistic genius.

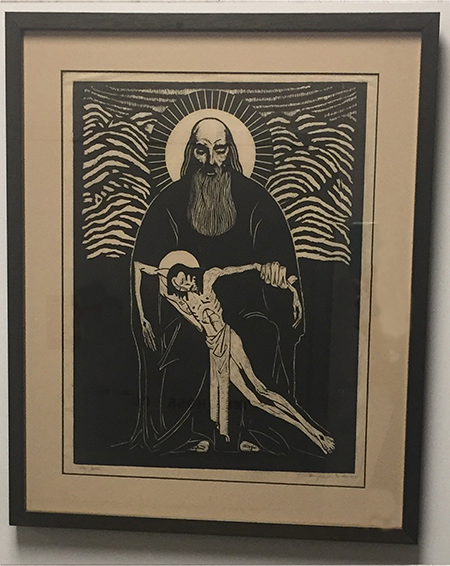

Miller’s art shows a pronounced sculptural character when featuring the powerful figures of God-Father, Abraham, John the Baptist, or Samson. It mutates to a poetic purity and lightness of being in his Annunciation and St. Francis and the Birds, whereas the events of Christ’s life – the Flight into Egypt, Christ Entering Jerusalem, Pietá – are surrounded by a great narrative stillness and sense of meditation. Miller’s 87 prints are works of brilliant precision. A man of quiet and intro-verted character, Miller felt the need to express the struggle and chaos of human life, the misery and injustice of existence. He not only represents the universal in art and the hidden splendor of religion, his prints, in a quiet but pointed fashion, point to the refugee, the blind, and the lame – to the world in quest of redemption.

Silhouettes

In 1923 Benjamin Miller began to experiment with black and white color schemes. One of the early works in this new style were the fifty-six silhouettes he created in 1924 for the Duveneck Society in Cincinnati. Three works on display in our exhibit are part of the Duveneck series: The Annunciation, St. Francis and the Birds, and Samson Destroying the Temple.

Silhouettes are identified with the beginning of art. They are mentioned already in Pliny's Natural History. From the paintings of Greek vases to the depiction of portraits in the 18th century, the silhouette drawing appears as one of the most popular means of combining linear accuracy and the graphic rendering of solid volumes. In the United States, silhouettes were highly popular between 1790 and 1840.

Miller's silhouettes — for him only a first step to the woodcut prints — are of fascinating beauty. They combine force and grace. They celebrate the intricate beauty of a flower or the silent hovering of a dove. There is movement waiting to explode, and story captured for eternity. Both hiding and revealing, the silhouette is promise never kept, but always open to creative imagination. And so the Annunciation becomes an event frozen in time, but alive in the present. St. Francis and the Birds is a gentle reminder that miracles are never far, and Samson a telling witness that raw force should be guided by a generous heart.

St. Francis and the Birds

St. Francis and the Birds

Expressionism and Religion

Benjamin Miller's woodcuts deal with a variety of themes from Greek mythology to topics of daily life. One of the main sources of his artistic inspiration was religion, the Old Testament as well as the New Testament. Miller shared his love for religious subject matter with the majority of early expressionists. Expressionism rejected the facile devotionalism of Saint Sulpice and mobilized the dramatic events and tragic figures of Judeo-Christian history for its art. The story of Isaac's sacrifice, the ordeal of chaste Susanna, Judith's heroic self-sacrifice, and John the Baptist's tragic death as victim of Herod's vanity and Salome's vengeance, are among the classical themes of expressionist art. Miller’s woodcuts on most of these themes are on display in our exhibit.

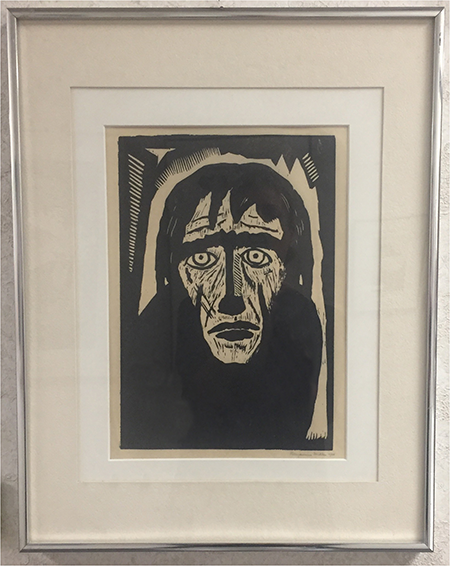

Religion for expressionism is a vehicle for the artist to express his personal experience and identity, marked most of the time by war, death, poverty, and, precisely, the loss of personal and cultural identity. Expressionism is not blasphemous. On the contrary, the similarity between the biblical story and the life of the artist attributes new value and dignity to the individual destiny. Thus, in the Bible stories God is depicted as seemingly cruel or impotent, the human being a tragic hero, human condition as paradise lost and never retrieved, and virtue, human virtue, is innocence ridiculed and downtrodden. Miller's prints "were more closely aligned with the print oeuvre being produced in Europe. These were provocative, intriguing images based on religious themes" (Allen W. Bernard). Two of the woodcuts included in our exhibit are particularly indicative of expressionist mentality and its perception of religion. One example is My Son (1928); the other is The Prophet (1924). The latter, The Prophet, shows some of the hesitation and heaviness of the beginning, My Son is an accomplished masterpiece of Miller's mature period. God is a projection of human helplessness and despondency. A massive figure, he is left impotent with the broken matchstick figure of his son in his lap. The human figure, represented in The Prophet, is a witness to psychological and spiritual homelessness. The Prophet, knowing and not knowing, torn between what to say and what not to say, is a wanderer between two worlds, belonging to neither and a fool in the eyes of everybody.

Miller and the Bible

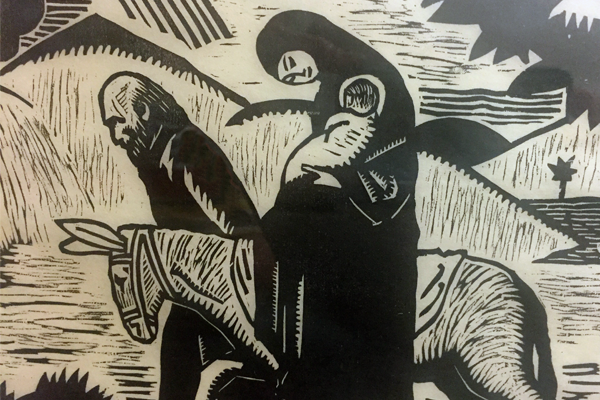

Benjamin Miller’s art received considerable attention beginning in 1927. 1927 is the year of the Salome prints and of the Flight into Egypt. The latter was included in the British publication The Woodcut of Today at Home and Abroad. It was commended for its bold and fresh design. The New York Times (December 25, 1927) published a full-size reproduction of the same print and presented it as a new look at traditional religious features.

The Flight into Egypt, a popular representation belonging to the Christmas cycle, comprises a multi-layered thematic. It highlights poverty, expulsion, and exile of the Holy Family; it records the clash between two cultures, the new culture — the culture of love — toppling the idols of Egypt — symbol of a world yearning for salvation. The Flight into Egypt also describes joy and bliss of the Holy Family on the rest from the flight, but already anticipates the future Passion of Christ.

Miller’s Flight is an intricate play of vertical, horizontal, and oblique lines. The Holy Family is set against the forbidding crisscross pattern of a hostile landscape. The child is blotted in the protective crucible formed by mother and donkey. Bent, but braving an uncertain future, Joseph combines the vertical and horizontal lines of Mary and the animal to symbolize resignation and determination.

The Bible has been strongly affected by 20th-century art. Contrary to 19th-century Bible illustrations à la Doré, which sought a certain catechetical and pastoral objectivity, beginning with the poetic and primitive symbolism of Gauguin (Vision after the Sermon, 1888), 20th-century art exploits the Book of Books as artistic quarry and source of inspiration. Events of the Bible are now translated into a second form (representation), attaining thereby a renewed presence and effectiveness. All at once, the biblical message opens itself to new interpretations and a variety of meanings. A symbiosis between artist and text develops which will give new life to the text and, to the artist, a home for his fears, phantasms, and expectations. The Bible becomes alive with a second life and breathes with two lungs: the lung of heavenly inspiration and the lung of human interpretation.

Flight into Egypt

Flight into Egypt

People and Faces

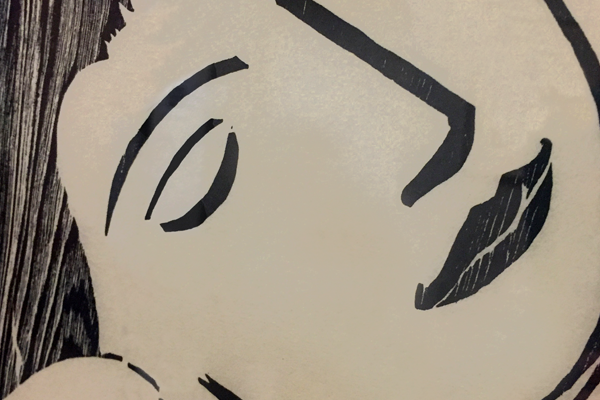

Benjamin Miller was a skilled and sensitive observer. The many woodcuts that picture individuals in various circumstances are an open book to melancholy, solitude, angst of indifference and rejection. There is a deep craving for understanding and bonding in many of Miller's faces. There is the hungry visionary look of the poet (Edgar Allen Poe), the faded seduction of the harlot, the timid expectation of the lady au café, and the dreamless face of the sleeping girl. Miller shows special empathy for victims of fate and social injustice. Part weary, part defiant, the face of the refugee tell the history of hope deceived. The lame man with blind eyes is scrutinizing a life curtailed and broken. The blind man has turned his life outside-in. His face is bathed in quiet interiority and radiates the peace of hope retrieved.

Miller's art, in some ways, is reminiscent of Evelyn Underhill's deep cravings. For the English mystic, each person is guided by three fundamental cravings which are to be a pilgrim, a lover, and an ascetic. We are pilgrims on the way to a lost home, a better country, our personal Eldorado, and ultimately to the heavenly Jerusalem. Lovers, our quest goes to the heart to heart, to the perfect soul mate, and our rest in God. Ascetic we crave for lost purity, the ideals of youth, and the elusive perfection that will make us holy.

Miller's work breathes the purity of empathy, the delicate touch of a loving and compassionate observer. There may also be the craving for elusive perfection, the silent swan song of lost and buried illusions. But the lover will keep the upper hand, and contentedly returns to the ordinary truths and simple joys of life.

Sleeping Girl

Sleeping Girl

A City on the Mount

A native of Cincinnati, Benjamin Miller was far from being a victim of his roots and culture. Living in Boston (1897-1901) and working toward a Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering, he was exposed to what he called “my New England culture.“ He will try to lose it working for a very short time as an engineer in San Francisco (1901). Eventually, he will return to California. In a fruitless attempt to find healing for his wife Ella, the couple will spend two years in Long Beach (1916-1918). To escape the grief of losing his wife, Benjamin traveled to Europe, visiting England, Holland, Italy, and France – spending the entire year of 1919 in Paris amid memories of bombed cities and desolate battlefields. He returned to Paris in 1921 and became deeply involved with expressionist art. Miller, an avid traveler, spent part of 1922 and 1923 in Assisi. In 1929, at a time when his work received recognition not only at home, but in Europe, he traveled again to Paris. The years after the Great Depression were frequently spent traveling with a friend not only to Europe, but also to Cuba and Mexico.

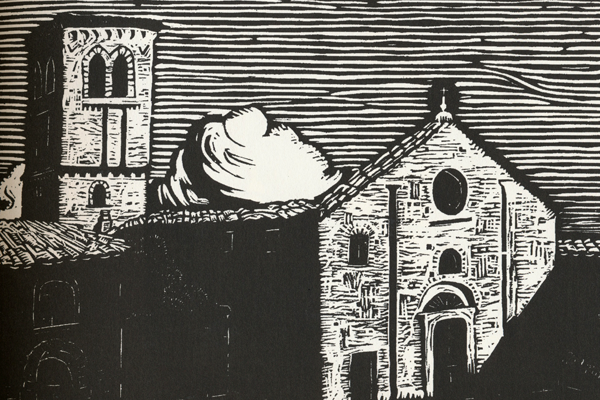

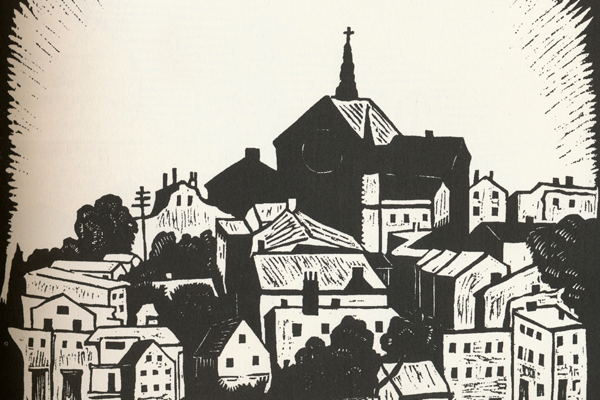

Two prints, both churches, in our exhibit are reminiscent of Miller’s travels. The first is Santa Maria Maggiore in Assisi (1927). The other is the Old Church of Taxco in Mexico (1927). The contrast between the two churches is memorable. Santa Maria Maggiore is broad, heavy, plunged partially in darkness. Colossal in an uninspiring way, the church looks with dark, blind eyes into the world. It is there to remain, so the message, but hardly here to attract people. The Taxco church, on the contrary, is full of southern charm. Although surrounded by an angry throng of clouds packed with rain, the mission church radiates joyful confidence, a serene and simple beauty. Was it Miller’s intentions to show two faces of the one Church: It’s sometimes forbidding permanence, but – most important – its never fading Light of peaceful hope and joy?

Architecture does not have an important place in Miller’s work. In the exhibit we have – aside from the two churches – a beautiful print featuring Mt. Adams, Cincinnati (1927) literally reaching into heaven and transfigured by the light from above. The woodcut is reminiscent of the iconographical motif of the City on the Mount. The City on the Mount is a symbol of life. It is the origin from which creation springs; it is here that life will find fulfillment. The seer of Patmos, in the Book of Revelation saw the Holy City, a New Jerusalem, coming down out of Heaven from God (Rev. 21:2). The City on the Mount is a symbol of redemption, of paradise retrieved.

Two of Miller's Most Significant Woodcuts

Benjamin Miller met some of his models and sources of inspiration in Europe, expressionists like Schmidt-Rottluff, Kirchner, and Heckel. He was familiar with the woodcuts of Gauguin and Munch. Two among the early expressionists, James Ensor (1860-1949) and Emil Nolde (1867-1956) left a more immediate imprint on Miller’s work.

There is no doubt about the great similarity between Nolde’s The Prophet (1912) and Miller’s 1924 woodcut of the same name. Nolde, the painter, is known for his love of vivid colors (Red Poppies, 1920; Sea and Light Clouds, 1935) and a marked religious period in his work (The Last Supper, 1909; The Burial, 1915). However, it was in print making that he found the means to express intense emotions in a radically simplified form. His most celebrated wood cut is The Prophet. The woodcut is hailed for the masterful combination of fluidity of form and intensity of expression. The hollowed eyes, furrowed brow, and sunken cheeks point to the ascetic, whereas the overall impression denotes a thoroughly spiritualized existence. Recovering from illness in 1909, Nolde saw in The Prophet a symbol of his conversion and of religiosity as such. Miller’s Prophet is more artisanal, in form as well as in expression. Eyes and face are haunted by what the prophet sees or blindly intuits. The Prophet is an early example of Miller’s print making. At the same time, his woodcut is typical of the suffering and critical look with which the Cincinnati artist perceived human reality and his own time.

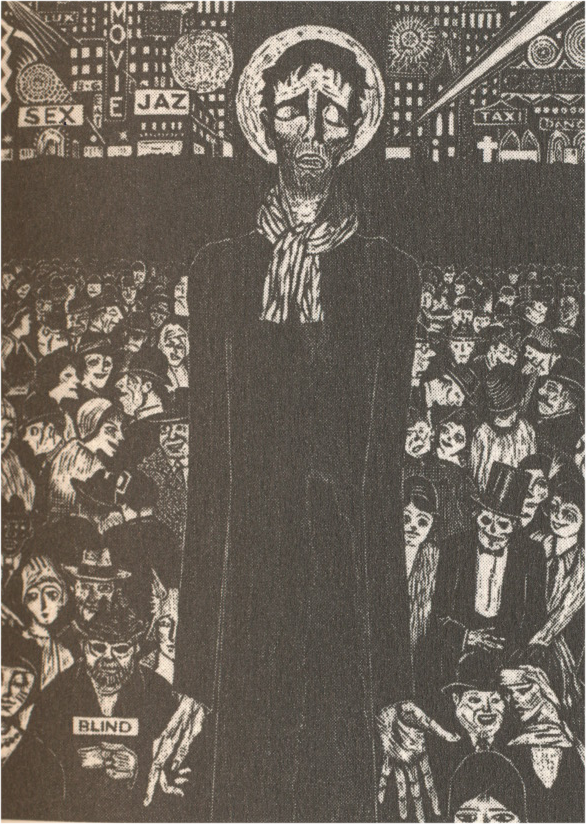

There is a second woodcut which points in a similar direction. Hailed as his most famous work, The City (1928) can be understood as a “secular sermon.” The 1930 publication of The New Woodcut commented as follows: “It is scathing satire on the fatuous frivolity and extravagance supposed to be rife in New York and presumably in other cities, regardless of the needs of the suffering poor, a crowd of inane faces of men and women of every description, laughing and giggling.” (A. Bernard, 17). The grinning and leering masses are pressing forward, literally pushing the Christ figure out of the picture. Oversized, but blind and empty handed, Jesus is an image of crucified impotence, a gigantic shadow without power, an irritating obstacle on the ways of the world. Miller’s secular sermon is reminiscent of James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1888). Rejected in the beginning, the first public exhibit took place in 1929, the contrast and similarity with Miller’s oversized Christ is easily perceived. Ensor’s diminutive Jesus, sitting on a donkey, is swallowed up by the same grinning and leering masses as in Miller’s woodcut. There is no singing, there are no palm branches on his way to Jerusalem. Ensor’s painting has primarily political significance, and his opinion on religion at that time bordered on cynicism. Miller, on the contrary, fustigated the cynicism of the masses on behalf of the poor, the downtrodden, and the poorest of all, Jesus.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.