Let's Talk Human Rights

Beyond Peril and Potential: Insights from SPHR 2021 (Part 6)

By Joel Pruce, Satang Nabaneh & Shelley Inglis

In late 2021, we gathered to tackle the question: What does human rights advocacy look like in the wake of the global pandemic? The Social Practice of Human Rights (SPHR) conference theme - “Between Peril and Potential” - responded to the multiple and overlapping crises we're experiencing with fierce urgency. At SPHR21, we asked participants to consider whether current human rights methods, strategies, and approaches are comprehensive, deep, and bold enough to meet this moment and leverage it for increased justice and dignity. This SPHR21 blog series captures discussions that occurred during the conference and reflects the innovative methods used to harness insights and promote action.

Toward a New Advocacy Paradigm

The dire state of our moment loomed heavy over our convening at SPHR 2021 and remains in the fore of our daily thinking. Confronted as we are with multiple, overlapping, and reinforcing crises, the list of challenges feels infinite: coming ecological collapse, creeping authoritarianism, rising white supremacy, and capitalism’s assault on dignity have manifested in specific and tangible threats to democracy, women’s rights and LGBTQ rights, to name only a few. These are hard times for those who care about human rights. They force us to ask the question: how can we, as human rights advocates, shift away from a perpetually reactive posture and reposition ourselves to affirmatively envision and determine a just future?

From reactive to pre-figurative

“Our struggles and resistances do not only react against oppression or advocate

for laws and protocols. They also build new institutions, relationships, economies.

They actually build other worlds that can prefigure the broader social-economic

transformations that we want to see.” - Raphael Hoetmer

When it’s an emergency all the time, actors do not have the time, space, or capacity to think, plan, and innovate. As emergencies mount and layer, advocates attempt to tourniquet the wound and slow the bleeding but cannot put together a preventative platform.

Many presentations at SPHR asserted that human rights provides a framework for guiding future-oriented political projects by setting minimum thresholds that must be met in order to guarantee a life of dignity. Such a forward-thinking approach applies human rights in their utopian mode, to outline what a decent society would look like and map out a way there. Too often, we affirm human rights norms in the breach (that is, when they are clearly abused), but human rights can also be tools for galvanizing aspirational formations with eyes set out on the horizon, beyond the slog of the present.

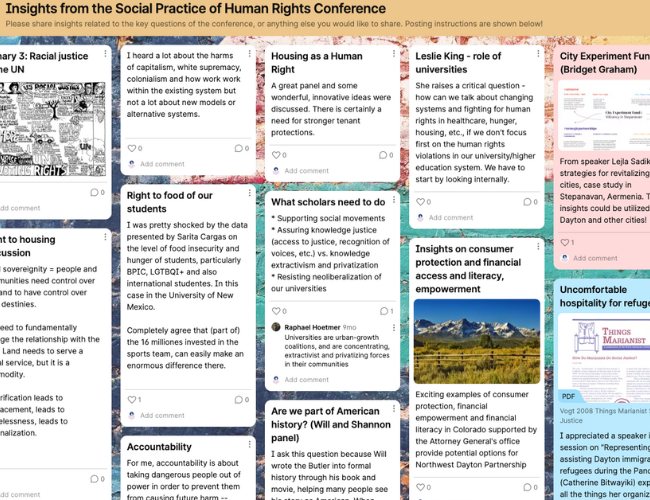

One commenter hit upon this theme from another angle: “I heard a lot about the harms of capitalism, white supremacy, colonialism and how to work within the existing system, but not a lot about new models or alternative systems.” Ideology, referenced here as “-isms” play a major role in mainstream discussions about power and politics in new ways not seen even a few years ago. This critique suggests that our grappling with the process of building new alternatives remains incomplete.

Creative and prefigurative thinking enables envisioning a future that does not yet exist and allows us to build a roadmap to get there. Seeding the future through a new human rights imagination emerges as essential in a moment fraught with despair and dead ends.

Holistic and pluralistic potential

“Human rights has the ability to highlight the overlap and intersections of

struggle and provide a common vocabulary for diverse movements to unite

around.” - SPHR participant

When human rights are described as “universal” it can mean an all-encompassing enterprise, applying to all, overriding our divisions, while acknowledging our particularities. While this view appears to offer an answer to all of the world’s questions and address all of the world’s problems, it puts more weight on the shoulders of human rights institutions than they can bear. At the same time, especially at a time of extreme polarization and atomization, the search for a holistic program girded by human rights is appealing.

Though a universal agenda, fragmentation among progressive movements hinders the ability to build together a forward looking human rights movement. Identity-based movements leverage some degree of homogeneity among its supporters while, hopefully, appreciating the way in which an intersectional analysis opens space for differences within the whole. For example, social movements, including the movement for Black lives and the Women’s March in the US, have encountered dilemmas within their ranks as individuals with intersectional identities struggle to find their place.

One way to view human rights as a “unifying” or “foundational language,” is to view it not as maximalist but as minimalist, as a system of norms, values, and laws that only thinly constitutes or bounds a political community. But what is community? As explored by Art Jipson during the Workshop on White Nationalist Movements and Alt-Right pandemic-related methods, community is not only a place, space and feeling, but is also a system and process that can be undermined through creative opportunities curated specifically to cultivate extremists.

Thus, it is important to not only see human rights as a useful organizing approach or tool, but also its holistic nature in motivating a politics of solidarity and cooperation amongst diverse constituencies.

While we acknowledge the immense complexities of human rights, we must also engage in a human rights project that generates hope. This project should be premised on the idea that mutual support and resilience implies recognizing pain, frustration and the loss of hope, and collectively trying to find ways out. Hope and promise are captured in the desire for “a unified voice” to counter belligerent intolerance, as organizer Alwiyah Shariff of Ohio Voice reminded us: “It’s hard to imagine change. I probably won’t be free in my generation. But we are fighting towards it.”

Moving to concrete social practice

So what is the way forward, we ask ourselves. There are limits to conventional and fixed thinking: for example, instead of reactive, be proactive; instead of being divided, let’s be united is not innovative. But we found at SPHR new ways of describing a way forward that transcends binary thinking. Nathan Law, pro-democracy youth leader from Hong Kong and SPHR keynote speaker, described his approach: Be water.

Famously, martial arts fighter and actor Bruce Lee put it this way:

“Be like water making its way through cracks. Do not be assertive, but adjust to

the object, and you shall find a way around or through it. If nothing within you

stays rigid, outward things will disclose themselves.

Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup,

it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You

put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be

water, my friend.”

This approach suggests that actors in human rights and justice struggles should plan to be adaptive through iterative actions shaped by immediate circumstances but informed by what’s come before. Nathan Law expanded, “Have the flexibility to modify as necessary to continue on your path.” Advocacy must be fluid, not static, and possess agility to respond to current circumstances thoughtfully and creatively.

This requires planning, creativity and flexibility that is easy to describe and difficult to cultivate. Traditional adversarial models of advocacy root our feet in the ground, digging in to face off. An individual in attendance captured this shift in thinking nicely:

“Nathan’s story challenged me to think about activism in a totally new way! We

always have this certain perception of what activism is or how it should be.

However, Nathan’s quote ‘Be Water’ helps in realizing that governments and

societies are always shifting and changing; therefore, we must ensure that our

activism is shifting as well.”

A new human rights advocacy praxis demands moving from thinking to acting and back to thinking to inform further action. As a participant in our World Café concluded: “Knowing better is not ALWAYS doing better, we MUST act.” The keynote of Erica Chenoweth raised the question of whether human rights activists are innovating at the same speed as authoritarian forces. The study of resistance movements is helping to share an evidence base about what works and can help keep movements ahead of the curve. As another participant remarked:

“Authoritarian governments and states are learning between them, sophisticated

repressive tactics and criminalization of dissidence. New technologies for

surveillance are used, and media and research journalists are repressed. It is

crucial we learn between movements and realities on repression and on

resistance.”

We came away from SPHR 2021 with the sense of a new direction in human rights advocacy: Learn. Evolve. Innovate. Analyze. Strategize. Act. Flow.

SPHR 2021

Erica Chenoweth Keynote

SPHR 2021

Erica Chenoweth Keynote