Let's Talk Human Rights

Beyond Peril and Potential: Insights from SPHR 2021 (Part 5)

By Joel Pruce, Satang Nabaneh, Shelley Inglis & Paul Morrow

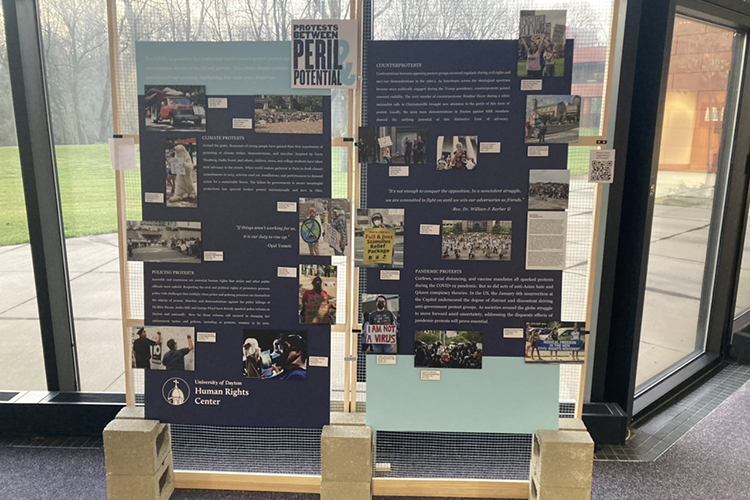

In late 2021, we gathered to tackle the question: What does human rights advocacy look like in the wake of the global pandemic? The Social Practice of Human Rights (SPHR) conference theme - "Between Peril and Potential" - responded to the multiple and overlapping crises we're experiencing with fierce urgency. At SPHR21, we asked participants to consider whether current human rights methods, strategies, and approaches are comprehensive, deep, and bold enough to meet this moment and leverage it for increased justice and dignity. This SPHR21 blog series captures discussions that occurred during the conference and reflects the innovative methods used to harness insights and promote action.

Reimaging old spaces as new

At SPHR, we directed significant critical attention to the roles played by elite spaces in the human rights ecosystem. Focusing particularly on universities and museums, speakers and attendees asked how we can repurpose the status, visibility, and resources of these institutions to better serve the interests of justice and dignity.

Museums

"Exhibitions that advocate for human rights and social justice are performances

of ideology in the world. When we acknowledge them as that, we can also locate

what sits outside of them: human rights violations.” -Willhemina Wahlin

The museum and curatorial communities are currently in the process of reimagining their roles within society at large. Traditionally founded by civic elites and housing artifacts which only the most privileged can afford, observers within and outside museums have been forced to ask what purpose such institutions serve in times of severe civil and political unrest.

From a human rights perspective, museums provide spaces for representation, truth seeking, education, and awareness raising around critical issues. Whether through photography, historical artifacts, maps and models, or other media, museum galleries provide opportunities to showcase the history and evidence of atrocity, the stories of victims and those impacted, and pose provocative questions for audiences to reflect upon. But in order to rethink how visitors interact with content, museum professionals must break with longstanding traditions of curatorial control and didactic display.

During the Perils of Visualizing Advocacy session, Amy Sodaro highlighted how memorial museums in the United States can serve particular functions as both agents and catalysts for change. For example, the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery, Alabama, was constructed near the site of one of the busiest slave auctions in the country. Honoring the history of this site of memory and tracing that history through to its modern manifestation in the U.S. prison system set the tone for the Museum. In tandem with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which chronicles the domestic terrorist violence of lynching, the installations cultivate a profoundly somber experience that challenges visitors to confront these pasts and make critical connections to the current moment.

Museums are working to transform their relationships with the public in creative ways. Calinda Lee emphasized the need to “model strategies for interpreting ‘difficult history’ truthfully and emphatically” through dialogue with all members of impacted communities. She described the development of a large new public park in Georgia’s capital which has provided the opportunity to tell the story of forced labor at the Chattahoochee Brick Factory during the Jim Crow era.

Artists are at the forefront of these transformations. Migiwa Orimo explained, for example, the “People’s Banner Workshops” that she convenes to offer local activists the chance to meet and collaborate on signs, banners, and posters that are used for advocacy purposes, and which may ultimately become part of collections of museums documenting our tumultuous present.

Visualizing advocacy at museums presents both peril and potential. Opening up interpretation and programming allows museum visitors to play a more active role in exhibitions and displays. It also creates the possibility for high-profile controversies within museums, as stakeholders with different interests or goals compete for influence over exhibitions and programming. As a social practice space for human rights, museums and their art and artists should be an increasingly central place for advocacy efforts.

Universities

“How can we talk about changing systems and fighting for human rights…if we

don’t focus first on our system.” -Leslie King

Universities are commonly viewed as gated and off limits–even and especially by communities closest to campus. They take up neighborhood space and resources, and are often vital players in local economies. As scholars seek to do more in the way of community-based projects with area partners, the baggage and weight of universities’ past actions burden attempts at bridge-building. So, how can higher education institutions acknowledge and repair their problematic relationships?

A promising point of departure is for universities to ask which human rights are promoted on their campuses as highlighted in the session, The Role of Universities in Promoting Human Rights in Cities and Communities. For example, research has found that while American universities are good at promoting freedom of speech, they are failing to ensure the socio-economic rights of their many students, particularly from communities of color or LGBTQIA, who are food or housing insecure. Food pantries and other partial measures on campuses are stigmatizing and ineffective.

A key dilemma, particularly for private institutions, is what Jackie Smith terms the “neoliberalization of our universities,” in which public goods (like access to education) are transferred and protected for private use by the rich. Increased emphasis on community partnerships and the branding imperatives of universities for social justice or the “common good” are in tension with the rising cost of higher education. In the absence of fair and equitable taxation and resource allocation, the private accumulation of wealth and resources facilitated by universities can directly conflict with public interest–a fact that people of lower socioeconomic status in campus communities know well.

Scholar-practitioners must confront the ideologies of their own institutions and be aware of how they represent and reproduce those ideologies and power when working in and with communities. Even deeply entrenched dynamics such as these are not insurmountable, though changing them demands rigorous and consistent intentionality in disrupting and destabilizing harmful power relations, while not reproducing binaries and inequities. Practically, scholar-practitioners can shift their approach to reorient research and community-engaged practice to better align with human rights principles.

Opening New Spaces, Creating New Places

“Great potential in bringing together different stakeholders, including artists,

curators, and groups, to engage in community organizing for democratic renewal.

Learning from each other is critical…Particularly, how to leverage creativity and

imagination for creative action.”- Satang Nabaneh

By opening spaces historically restricted to privileged access, institutions like universities and museums can play critical roles as conveners and catalysts for change. In many places, universities do not enjoy independence from political authorities, as the recent dismissal of faculty and students from universities in Hong Kong makes clear. But even in those places, they can provide some space for youth-led activism against authoritarianism, which Nathan Law exemplified in his keynote address.

As Jackie Smith insisted, “Place-making is essential to change-making.” Convening and holding space can be powerful community building tools; respected institutions are uniquely positioned to serve in this way. Engaging strategically with broader movements and communities in new and existing spaces enables deeper learning and the elimination of silos.

Universities and museums generate and convey knowledge. Prioritizing epistemic justice or what we might call “knowledge justice” through the recognition of beliefs, voices and experiences from those who do not call these spaces home serves as an antidote to “knowledge extractivism” and the logic of privatization. “There is no social justice, without epistemic justice” as declared by Tspeho Madlingozi in the session, Approaches to Decolonizing Human Rights Education.

The promise of museums and universities is that they are essential to a thriving democratic society. It is not a given, however, that the resources and spaces of these often powerful and prestigious institutions are devoted to fuller articulations of the public interest, human rights enjoyment and the common good. Only by acknowledging the peril of reinforcing old hierarchies and entrenched privileges can these spaces be reimagined to achieve their full potential as spaces for social transformation.