Let's Talk Human Rights

Art Against Authoritarianism: Crack Rodriguez at UD

By Miranda Cady Hallett

Human Rights Studies and the department of Art and Design invited Salvadoran artist and activist Crack Rodriguez to the University of Dayton, where he shared his thoughts on the current crisis of violence in El Salvador as well as the struggles of immigrants seeking safety in the United States.

“And the ice represents…?” I ask.

“ICE,” he says, “the immigration enforcement system [in the U.S.]. The ice represents ICE. It represents the weight that bears down on all migrants because of the fear of deportation, and everything that goes with it.”

He turns towards me with a big smile, and goes on to say “what I like about conceptual art is that you can make the concepts simple. You don’t have to complicate things.”

As an academic, that just might sting a little bit to hear. But I also know exactly what he means—and for the last eight years or so, the man sitting across from me has been calling out authoritarianism and corruption, and calling for a more just and humane world. He does so through performance art and direct political actions whose meanings are hard to miss.

We’re sitting in my office in the Human Rights Center in Keller Hall, and Salvadoran artist and human rights activist Crack Rodriguez is explaining what I might want to know about his recent work before I serve as his interpreter for the public talk at the University of Dayton. The particular piece in question, a performance titled “El Peso del Destino/The Weight of Destiny,” was created during his time in Oklahoma earlier in 2022 with the Tulsa Artist Collective. In it, he held a giant block of ice suspended in a hammock hooked to a monument in downtown Tulsa, bearing the weight until the block melted.

As he did so, people passing by would comment or try to lift the heavy block themselves, becoming part of the performance.

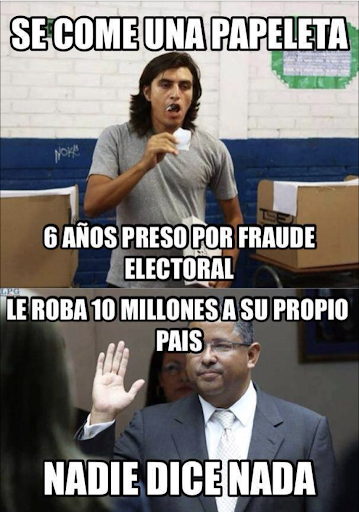

As a researcher working on El Salvador, I first heard about Crack Rodriguez’s work around 2014 when he made minor headlines by walking into a polling location during the election, declaring “this is an artistic action,” eating half of his ballot, and depositing the rest in the ballot box.

Unpacking his motivation behind the action that left him with the nickname “El Comepapeletas” (the Ballot-eater) at the University of Dayton’s Boll Theatre on November 16, the artist says, “I started to think, what is the most politically powerful moment for most of us? It’s when we vote. So how can I get more power? I thought, maybe if I eat the ballot, I will nourish myself with the vote. I will feed myself with political power.”

This meme drawing on imagery from Crack’s 2014 performance made the rounds on social media, critiquing the ways government corruption goes unpunished while an artistic action was criminalized as “electoral fraud.”

This meme drawing on imagery from Crack’s 2014 performance made the rounds on social media, critiquing the ways government corruption goes unpunished while an artistic action was criminalized as “electoral fraud.”

Later, over coffee, he elaborates on more layered meanings behind the ballot-eating action. “It’s also about the lack of power that the vote represents in the context of a consumer society,” he says, “when a vote can be bought and sold, political ideals swallowed, what is it worth?” Such questions are crucial in countries facing not just the threat but the reality of democratic backsliding.

His action that day, and the resulting political and media attention, caused a major shift in his own life. “I remember walking in there that day conscious of the fact that there would be no going back. That once I did this, it would change my life—surely, they would look for me, and surely they would arrest me.” Before then, Rodriguez had been working on a political campaign for a progressive politician in El Salvador. When he saw things that led him to believe the party he worked for was bribing voters and using violent actors to influence the outcomes, he became deeply disillusioned.

Countercultural spaces, like performance art and street protest, were the only places he could see where his ideals of democratic practice and free expression could still find breathing room.

The story of the ballot-eating action formed one small part of an hour-long multimedia presentation in Boll Theatre, with Crack showcasing his varied interventions in the Salvadoran and U.S. political and cultural scene. These interventions include ongoing collaborative work with the Fire Theory Collective, like a 2017 piece on migration and borders funded by the New York State Council on the Arts, and performance-actions documenting and confronting Salvadoran state violence and its consequences with Los Siempre Sospechosos de Todo (“The Usual Suspects”). Many of his performances seamlessly involve social engagement and direct actions– work to free prisoners, for example, to connect survivors of human rights abuses in El Salvador with legal aid, to promote post-war reconciliation through soccer, or to defend indigenous territories against corporate dispossession.

Existing in a praxis at the intersection of performance art, protest, and direct mutual aid, Crack Rodriguez’s work has definitely attracted international attention: he received an emerging artist grant from a Colombian foundation in 2014, secured a residency on “Art and Activism in Latin America” in Rio de Janeiro in 2016, presented at the CreativeTime Summit in 2017 in Toronto, and was commissioned by Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions and the Museum of Latin American Art for a piece called “Dream Team” earlier this year– as well as the collaborations in Tulsa. And most recently, he arrived here to Dayton, Ohio to visit classes, perform on campus, and provide a space of encounter to share his ideas and observations about today’s crisis in El Salvador.

“The rule of law no longer exists in my country,” he claims, while describing the ways in which El Salvador’s president, Nayib Bukele, has systematically dismantled the rest of the government, consolidating a “state of exception.” Under Bukele’s authoritarian rule, military and police have carried out mass arrests– packing already horrific and overcrowded prisons– and the legislature suspended due process rights. The government has sent the military to surround entire neighborhoods and put them on lockdown. Comparing the country to the Philippines under Duterte, Crack points to the repression of these mass arrests– and an unknown number of disappeared– saying “In my country, it’s a crime to be young. It’s a crime to be poor. It’s a crime to have indigenous features.”

In addition to migration, democratic crisis, and political violence, Crack’s work frequently addresses themes of consumerism, contested memory, the erasure of indigenous people in Salvadoran history, reconciliation in a post-conflict society, and the intimate forms of violence found in family and school settings. It’s not surprising, therefore, that his performances have often been controversial and poorly understood, with observers sometimes dismissing his work as simply disrespectful or absurd.

That doesn’t worry the artist, though. As he said to us from the Boll Theatre stage, “when they tell you it isn’t real art, that’s good—that’s when you know it’s working.”

Miranda Cady Hallett (PhD Cornell University 2009) is Director of Human Rights Studies, Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology, and a Human Rights Research Fellow at the University of Dayton. Miranda is an engaged public scholar and educator with a commitment to social justice movements in North America. She has published extensively on human rights and migration, most recently a co-edited volume titled Migration and Mortality (2021) from Temple University Press, and an article in Citizenship Studies (2022) on resistance to state violence and abuse in the Butler County detention center in southwest Ohio.

Testimonio de los Restos/Testimony of the Remains

This compilation of moments from “Testimonio de los Restos/Testimony of the Remains,” Crack Rodriguez’s November 16 performance at the University of Dayton, shows the artist weaving a dream-catcher with barbed wire, feathers, and twine as the snow falls over Humanities Plaza. © 2022 Crack Rodriguez