Let's Talk Human Rights

Beyond Peril and Potential: Insights from SPHR 2021 (Part 4)

By Satang Nabaneh, Shelley Inglis & Joel Pruce

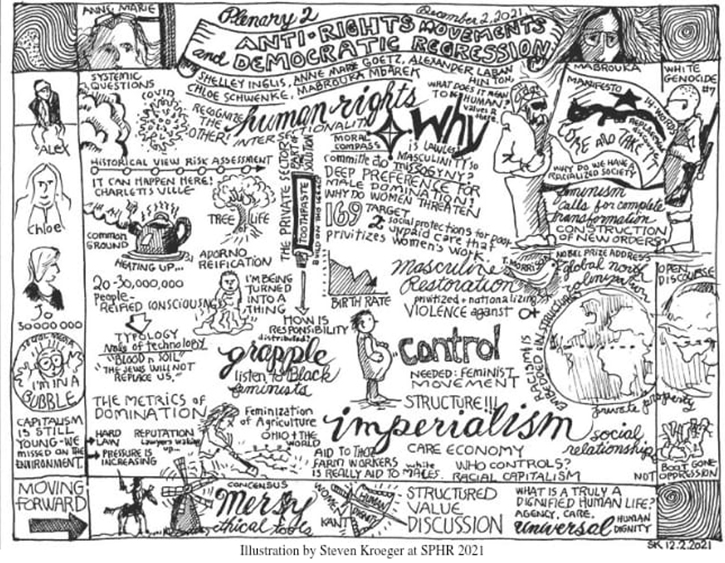

In late 2021, we gathered to tackle the question: What does human rights advocacy look like in the wake of the global pandemic? The Social Practice of Human Rights (SPHR) conference theme - "Between Peril and Potential" - responded to the multiple and overlapping crises we're experiencing with fierce urgency. At SPHR21, we asked participants to consider whether current human rights methods, strategies, and approaches are comprehensive, deep, and bold enough to meet this moment and leverage it for increased justice and dignity. This SPHR21 blog series captures discussions that occurred during the conference and reflects the innovative methods used to harness insights and promote action.

Reshaping human rights movement-making

At SPHR 2021, we sought to answer the question of how different movements, organizations and activists — who seek justice and dignity from various lenses, identities, and approaches—interrelate in this current era. In exploring this, we found that human rights advocacy is more impactful today when it is grounded in critical, intersectional and decolonial feminist approaches. In this way, our actions are better anchored and equipped to directly address the root causes of structural violence and oppression.

Varying methods and tactics of campaigning strategically

In the era of increasingly corrupt and authoritarian governance, non-violent civil resistance movements have been at the forefront of human rights struggles in the U.S. and many countries around the world. Through keynotes, plenaries and roundtables, we explored a range of these movements and the factors that make for successful campaigns. In their keynote, Erica Chenoweth explained that the ability to vary methods throughout the course of the civil resistance movement is a key factor in the movement’s success. These methods include, for example, boycotts, building parallel institutions, protests and other forms of noncooperation. They also noted that employing varying methods effectively requires high levels of strategic leadership which can be difficult to maintain in today’s social movements.

The plenary on Civil resistance & social movements of 2020 showcased movements achieving various levels of success in places like Belarus, India, Chile, and Sudan. A challenge is coordinating and sequencing various methods over time which requires strategic levels of community organizing and coalition building to maximize participation of people across a range of sectors in society. The extent to which movements draw in a diverse cross section of society, including those who are a part of repressive institutions, is critical to success. Human rights advocacy must more fully embrace the strategic use of varying methods and tactics of advocacy to build more effective campaigns.

Feminist leadership

“Are there any human rights issues that do not connect back to the politics of

masculinist restoration?” Natalie Hudson

In the current context where major regressions are being taking place across human rights protections, feminist leadership and lenses emerged as integral to understanding and defining human rights challenges. They also are essential to identifying effective responses across many issues, such as corporate accountability, human rights education, and civil resistance and democratic renewal. During the plenary on Civil resistance and Social Movements of 2020, for example, Margarita Maira pointed out how Chile had successfully established the first ever gender balanced constitutional convention because of the effectiveness of the feminist movement in organizing for and through the popular democracy uprising. As noted by another person in the Padlet, “feminist movement did its job! Tireless.”

In the session, Corporate accountability in transitional justice: reflections on an ongoing social lab, the question was posed, “What happens when transitional justice becomes feminist?” The work of the social lab is not simply about women-led leadership or the fact that women carry the disproportionate burden of corporate violations in conflict affected societies, but also about a “relational ethos” that is built, inspired by design logic, which creates a different space of mutuality that allows for the new strategies to emerge.

Also in the roundtable on Feminist Leadership, Gender-Based Pedagogy and Educating Future Practitioners, scholar-practitioners explained how feminist practices like collaboration and facilitation are vital tools for deep cultural change in the human rights space. The strategy of sharing a vision based on reflexive learning and the willingness to unlearn counters restorative and revanchist patriarchy. This also requires examining and contesting expressions of oppressive power that feminists may reproduce, confronting them, and co-creating just and intersectional alternatives.

Intersectional organizing

Today it is common for rights and justice advocates to utilize an intersectional lens in their work: that is, a structural analysis of systems of violence and domination, like capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy, that recognizes the simultaneous ways that people experience multiple oppressions based on their multiple identities. Applying this to campaigning, organizing cooperatively to reach common aims across groups with multiple identities, priorities and experiences emerged as a critical strategy to create solidarity across issues, organizations, and communities. The Indian Farmers Protest, which sought to repeal controversial farm laws that would privatize farming, was an example shared that described how an intersectional approach to organizing centered the lives of the most marginalized. As a result, women have taken on an important role in this struggle, becoming more present as protesters in public, and galvanizing conversations about the space for and role of landless farmworkers, not just the landowners who started the movement.

There is a new urgency for social justice, human rights movements and grassroots organizing efforts to connect and support one another in response to the rise of authoritarian governance and revitalization of white supremacy, xenophobia and extreme nationalism. This encapsulates a way towards building solidarity across issues, organizations and communities, and utilizing an intersectional approach by centering the experiences and leadership of people affected by multiple forms of oppression. Indeed our resistance not only reacts against oppression but can, as Awino Okech in the Decolonizing Human Rights Education session noted, “build the type of [movement] we want to see!”

Critical self-reflection

“We all just assume that we're here […] we don't ask why. There's such a great

missed opportunity to bring ourselves present to say why we care. And that

would have been a great opening for all of this is just to begin to say, I really

care, and here's why."- World Café participant

This serves as a reminder to human rights advocates to not only know who we are and our strengths, but to also express the reasons why we care, which are deeply personal and often inspirational. In doing so, we must also deal with our own privileges which are often what enable us to do human rights work. For example, a participant critiqued how the “imperialist lifestyle” “challenges us to consider how the Western way of life, not only developed out of the extractive practices of imperialism and colonialism,” is also insufficiently explored in current discourses and research. Creating spaces for and engaging in critical self-reflection about our positionality and how it informs our advocacy methods is crucial for the social practice of human rights. Practically, spaces for collective reflection should become an integral part of our convenings as well as the academy, because, as Raphael Hoetmer recalled, “it's a way of building knowledge of doing research, of thinking, of action.”

Critical self-reflection can help position human rights actors to envision tactics and design strategies that are iterative, adaptive, and fluid by challenging routinized practices with new thinking. For example, a reflection in the padlet on ‘racial justice - nowhere near?’ reminds us that “those who are part of the system, those who benefit - that is, white people should do the work. [The] burden should not be on the oppressed.” Drawing on Chenoweth’s description of successful movements that peel away support from the parties within the state, in this case, would require more white people to relinquish their privileges and develop new tactics that draw on their specific positionality in the struggle for racial justice. There will be no change without self-reflection, accountability and confrontation within human rights spaces.

SPHR 2021

Youth Leadership in Civil Resistance & Social Movements 2020

SPHR 2021

Youth Leadership in Civil Resistance & Social Movements 2020