Let's Talk Human Rights

Our experience of mapping mass graves in Raqqa, Syria

By Aidan Mornhinweg '24, Haochun Ling '22

In late fall 2021, the University of Dayton’s Human Rights Center, its Mann Chair in Natural Sciences, and its Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences, along with the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) Scientific Responsibility, Human Rights and Law Program undertook a new Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and human rights investigation at the request of the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC). SJAC is a non-profit justice and legal documentation organization that monitors and reports on violations by various actors in the Syrian conflict.

For more than a decade, Syria has suffered from internal conflict that has been further complicated by the engagement of international players, including Iran and Russia (allies of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad), Qatar, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia (which support opposition forces against Assad’s government), and a U.S.-led multinational coalition. Between 2013 and 2017, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) or Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) controlled northern Syria, with Raqqa as their nominal capital. According to SJAC’s interactive map of ISIS grave and prison locations, approximately 6,000 bodies have been exhumed from dozens of mass graves created by ISIS in northeast Syria and retrieved from buildings destroyed by Coalition airstrikes.

The project’s objective was to establish a satellite-based chronology of events surrounding the creation of eight mass graves in Raqqa city and province in northeast Syria which were initially identified through the exhumation efforts of the Syria Missing Persons and Forensic Team (SMFT). The work was intended to assist Syrian groups in identifying the victims from the exhumed remains, ensuring that families of the missing know the truth and ideally holding perpetrators accountable for the killings.

How did we join the GIS & HR project on Syria?

Aidan: I first learned about the project via a campus-wide email. I was curious about the opportunity to be trained in the use of GIS software and technology to identify potential human rights violations, particularly in Syria. The chance to get hands-on experience with new technology was what hooked me. After attending the first training session and orientation with the GIS team, I was confronted with the grim reality we would be researching mass graves, but that didn’t daunt me.

Haochun: I am in my third year of law school at the University of Dayton and am interested in international human rights law and immigration law. I joined the HRC as a graduate student researcher. Part of my responsibility was to support the HRC in implementing this GIS project. I was very excited to join the project and attended the training on the application of GIS technology to human rights cases.

What have we learned?

Aidan: Since joining the project, I learned a lot about both GIS and the situation in Syria. I’ve been working with an amazing team of student and professional researchers and human rights practitioners. The data we gathered is crucial for identifying persons who have gone missing due to violence and conflict caused by war and ISIS fighters in Syria. According to the data we received from SJAC, known missing persons included civilians as casualties of the war, ISIS fighters, prisoners from ISIS camps and soldiers from the Syrian army. The sites we were investigating are all located in northeast Syria, primarily the desert province of Raqqa and the city of Raqqa.

In this project, my task was to analyze satellite images and collect quantitative data. I was part of an image analysis team that consisted of two other members and me. Each member was assigned a section of images. At least two images were analyzed, one that revealed the first appearance of potential burial sites and one that indicated the most recent burial sites and soil disturbances. Doing this allowed us to make a timeline of events so we could pinpoint when and where potential burial sites emerged.

SJAC gave us a list of sites of interest, asking us to help establish a probable timeframe of when the mass graves were created as a means of assisting the search for missing persons. Exploring precisely what, how, and why someone was buried is the responsibility of our partners who have boots-on-the-ground connections and can confirm the accuracy of our data. As researchers, we collected data and quantified each data point as a “point” or “object-of-interest” to be investigated later by our partners. Thus, it was crucial we didn’t speculate about the data we were quantifying. An example of the work I did with my team is below in Figure 1.

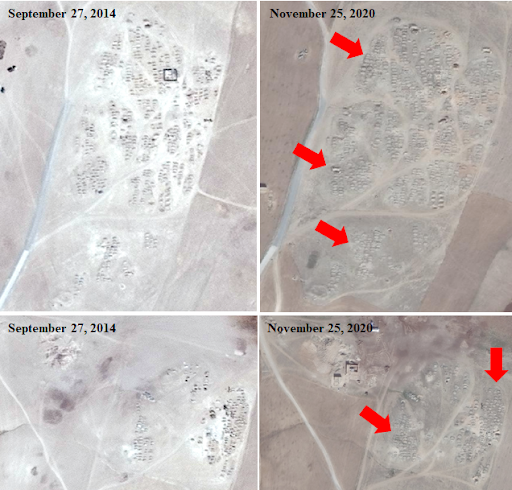

Figure 1: Site 24 in Tell Zeidan, near al-Hamrat just east of the city of Raqqa.

Figure 1: Site 24 in Tell Zeidan, near al-Hamrat just east of the city of Raqqa. This example shows Site 24 which is a pre-existing mass grave site, with excavation work initiated on April 13, 2020 and continuing today. SJAC has reported 234 exhumed human bodies, of which most are believed to be missing soldiers from the Syrian Army (all bodies were young men in army uniform). Our team searched through an online archive of satellite images and established the most likely timeline of events concerning the creation of these mass graves, which was September 27, 2014 to November 25, 2020. As of 2014, I determined approximately 607 points-of-interest and approximately 1,032 points-of-interest by November of 2020. This means that between 2014 and 2020 there were 425 new points-of-interests. In Figure 1, nearly every visible depression, hole and mound is a potential grave or part of a larger network of graves. While I examined Site 24 from an aerial perspective, I utilized ArcMaps and supplemental software to precisely pinpoint potential graves by zooming in on them while retaining a very high resolution of the image. While in ArcMaps I created a digital “layer” that allowed me to collect data points on every potential grave by marking my image with thousands of “annotations.” These annotations can simply be small triangles, circles, or any shape that is embedded into the layer. This means that when I analyzed Site 24 there were over 1,000 different annotations that littered the image. The images used here don’t show all the annotations, but the red arrows shown in Figure 1 are an example of the type of annotation.

Haochun: When I first signed up for the GIS project, I was very excited to explore this completely foreign study area. I took this opportunity to develop my technical skills, and traditional legal and writing skills as my research informed the human rights implications section of the brief analysis we produced. After the initial excitement, I became aware of the stakes of this work. Our GIS project is of great importance to the local Syrian families. As I marked up the mass graves on the map, I could visualize people buried in these graves, a representation of the atrocities of the war. As I pinpointed locations on the map, I could hear the "boom" of the bombs that destroyed so many families: mothers who lost their sons and daughters; wives who lost their husbands; and many children who lost their parents. The research I did on the human rights implications helped me acquire knowledge about the practical implications of the war and human rights violations in Syria, which has broadened my worldview. It also strengthened my goal of contributing to the protection of human rights after graduation.

The potential value of our work

Our project's work to establish a satellite-based chronology of events surrounding the creation of eight mass graves within Raqqa city and province was incorporated by SJAC in its latest report, Unearthing Hope: The Search for the Missing Victims of ISIS. We hope that our satellite imagery analysis will assist in identifying the exhumed remains, eventually allowing families to recover the remains of their loved ones and perhaps one day hold perpetrators accountable.

Aidan Mornhinweg is a second-year undergraduate and Flyer Promise Scholar in the College of Arts and Sciences, majoring in History and minoring in Computer Science. At the Human Rights Center (HRC), Aidan works as an intern with the GIS and Human Rights Project. His interests in human rights focuses on people affected by local and global conflict, particularly wars, genocide, and other instances of mass violence inflicted against civilians and combatants alike.

Haochun Ling is in her third year of law school at the University of Dayton. Her focus is on international human rights law and immigration law. She joined the Human Rights Center as a graduate student researcher. She intends to utilize her understanding of immigration law and international human rights law after her graduation in 2022 to assist persons in the process of getting US immigration benefits or to assist asylum seekers in the United States.