President's Blog: From the Heart

A Nobel Soul

By Eric F. Spina

During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, the University of Dayton pays tribute to our students, graduates, faculty, staff — and our Nobel Laureate.

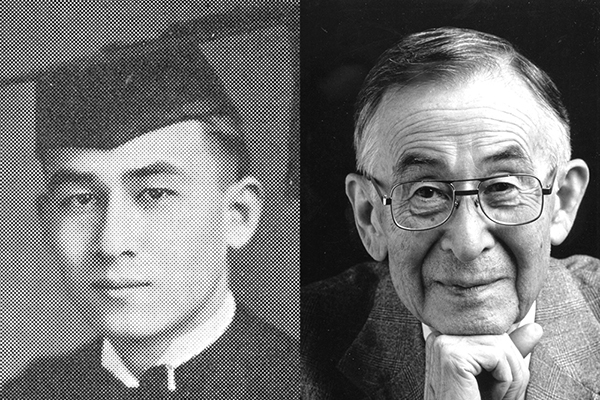

Charles J. Pedersen, described as “a brilliant chemist with the soul of an artist,” shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1987 for his discovery of crown ethers, which are used in many applications today, including removing mercury from drinking water. Although he graduated in 1926 — three decades before the birth of the University of Dayton Research Institute — his legacy of creativity and innovation continues to inspire today’s scientists, researchers, and students.

Just eight months before Pedersen died in 1989 from blood cancer and Parkinson’s disease, then-president Brother Raymond L. Fitz, S.M., paid a visit to Salem, New Jersey, to present him with an honorary master’s degree in his living room. With humility, he turned down an honorary doctorate. This feature story about that visit is reprinted from the Feb. 24, 1989, issue of Campus Report.

For the past two decades, University of Dayton alumnus Charles J. Pedersen has lived the life of a quiet citizen in this tiny Norman Rockwell-like town.

He played poker with his buddies, wrote poetry, worked in the garden, enjoyed birdwatching, dabbled in watercolor painting.

And then he won the Nobel Prize in 1987 for his discovery of crown ethers — substances that make it possible to synthesize numerous complex agents.

It’s made it hard to live the quiet life, though Pedersen has lost none of his unassuming nature.

“What I did, I did well,” he reflected. “I worked in a peculiar way and things worked out. If you have an abnormal way of doing things, you do have an advantage because you’re not imitating anybody else. If you have innovation, then you’re relatively safe.

“But it doesn’t mean you necessarily have anything good,” he quipped with characteristic wit.

The soft-spoken retired industrial chemist, 84, shared anecdotes of his college days in Dayton and drank champagne with UD officials when President Brother Raymond L. Fitz, S.M., presented Pedersen with an honorary master’s degree on Feb. 9. Last March, the University gave Pedersen a Distinguished Alumnus Award.

“I’ll treasure it,” Pedersen told Fitz after he presented the citation and degree before a living room full of relatives and friends in the scientist’s quaint 18th-century house. “I’m sorry I’m not in better condition to do things like lectures.”

Pedersen stepped back more than 60 years to recall people and experiences at UD, then a college of 400 male students. “By and large, I had a very pleasant time,” he said.

Pedersen was born in Pusan, Korea, to a Norwegian father and Japanese mother and spent most of his childhood in Japan. He clearly remembers UD campus life because it was the first time he had ever lived in America.

“In Japan, if you wanted your shoes cleaned, you just put them outside the door,” said Pedersen, who studied at a convent school in Nagasaki and St. Joseph College, a preparatory school run by the Marianists. “When I came to the University of Dayton, I thought the dormitory was equivalent to a hotel. My goodness, the next morning there were no shoes. I went to see the man in charge (of the dormitory) and he said, ‘Well, that was a darn foolish thing to do,’ and that,” he said as the group erupted into laughter, “was the only consolation I got.”

Pedersen, one of only four chemical engineering graduates in 1926, excelled in tennis and track and earned gold medals for academic excellence and conduct.

He thinks he’d have “a tough time” in college today. “I think college students need more fortitude now. There’s much more to learn for one thing. It was easy for me. I hardly did any studying at all, and I couldn’t possibly get away with that (today).”

Discipline and persistence paid off for Pedersen, whose research over his 42-year career at E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company yielded 65 patents, mostly in petrochemicals.

After Pedersen’s initial discovery, American chemist Donald J. Cram and French researcher Jean-Marie Lehn developed more complex crown ethers and evolved the science known as host-guest chemistry. The three shared the coveted Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Scientists say crown ethers, whose potential has not been fully explored, could lead to the development of new pharmaceutical delivery systems, radioactivity antidotes and extractors of gold and uranium from the sea. “On the other hand, they may not make a cent,” Pedersen said wryly.

His colleagues describe him as “a brilliant chemist with the soul of an artist,” someone who would be just as content painting watercolors as conducting chemical research.

How does Pedersen want history to remember his greatness?

“The only honest thing I can say is as a man who knew what he could do. I really can’t do other people’s work.”