Blogs

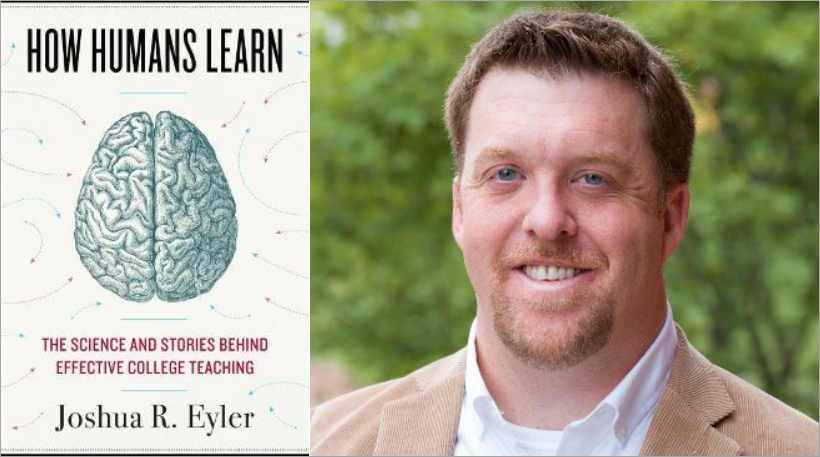

Book Review: How Students Learn by Joshua Eyler

By Kent Darr

Teaching is one of the most celebrated but misunderstood professions on the face of the earth. And who can blame those who misunderstand it? For the last several generations, the educational system has endured withering criticisms from both inside and out while continuing to produce scholars who innovate and discover on a regular basis. So how do we reconcile the seeming inconsistency of a system that is often judged as wanting and its fruit of pioneers and entrepreneurs? It turns out that the content being learned is only part of the equation, while the other half is far more primal in origin.

In his book, “How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories behind Effective College Teaching,” Joshua R. Eyler explores the evolutionary history of the human brain to pinpoint a set of five common needs that drive all humans to learn from the world around them, including: Curiosity, Sociality, Emotions, Authenticity, and Failure. In essence, Eyler finds that when left to their own devices, our ancestors learned through a mixture of nature and nurture that we can still use to make learning the visceral, intuitive experience that it once was, and which continues to inspire many of the greatest creators of today.

Curiosity:

Curiosity is such a fundamental instinct in humans that our brains actually reward us with a sense of pleasure for simply having learned something new. Much like any other skill though, curiosity can be inadvertently killed by educational structures that reward only success and performance. To build a classroom that rewards curiosity consider designing research projects where students ask their own questions, facilitate open ended discussions while asking “Why” questions that can open further lanes of inquiry, or ask ‘metaquestions’ about the goals of the course, which can lead to wholesale course redesigns so that the content, materials, and activities of the course are all intended to answer the questions being asked.

Sociality:

We are fundamentally social creatures, and in fact, may have one of the greatest needs for socializing in the entire animal kingdom. As a species, we can feel actual pain if and when we are deprived of social interaction for too long. This means that your students’ constant chatter or disruptive notes aren’t a bug; they’re a feature. Like it or not, each of us has an intrinsic need to communicate with, imitate, and engage in playful activities with those around us. You can embrace this need by embedding opportunities for social interaction in your course such as discussions, group projects, peer to peer feedback and even games.

Emotions:

The emotions that a student experiences during class time should be considered to be of equal importance with the actual information that we are trying to teach them. Why? Because each student represents a unique and interconnected web of emotional and intellectual capacity that benefits from the genuine presence and care of others. Sharing your enthusiasm for the subject matter, utilizing humor in your presentations, and instilling a sense of safety to fail into your course can all lead to significant gains for students who might otherwise be checked out of your course.

Authenticity:

Our brains privilege information that has inherent meaning and ignore, or at least diminish, ideas that don’t communicate their significance to us. Thus, students are much more likely to meet their learning goals when they are given chances to immerse themselves into academic work that looks, feels, and smells like it could be done in non-academic environments. To make your courses more authentic, consider giving students more chances to engage with research activities or projects that require them to answer questions, use tools, or engage with their colleagues in ways that they would in the professional world.

Failure:

We fail frequently and sometimes fantastically, so it only makes sense that our brains have adapted to quickly learn from our mistakes so that we can succeed in our next encounter with a challenge. Unfortunately, the traditional practices of the educational system such as grades and GPAs make it difficult for failure to truly benefit students for the long-term. Thus, embedding opportunities for “productive failure” requires both a change in teacher mindset and course design. Practically, you can leverage failure in your courses by designing assessment strategies that encourage students to take risks and challenge themselves while simultaneously emphasizing an approach to learning that focuses on skill growth rather than standard meeting.

Teachers and learners may never produce the cut-and-dried results the way that we (or they) might like. But people are uniquely adapted to learn from our messy existence and overcome challenges of all kinds, like hunting for prey, raising crops, creating civilizations, or sending rockets to the moon. Using Eyler’s thesis, we can approach the classroom with the recognition that we humans have and always will continue to learn in circumstances that might be considered informal, suboptimal or both. So, next time that you enter your classroom, consider how you might appeal to your students’ base instincts along with their higher level aspirations. Their brains will thank you for it.