Blogs

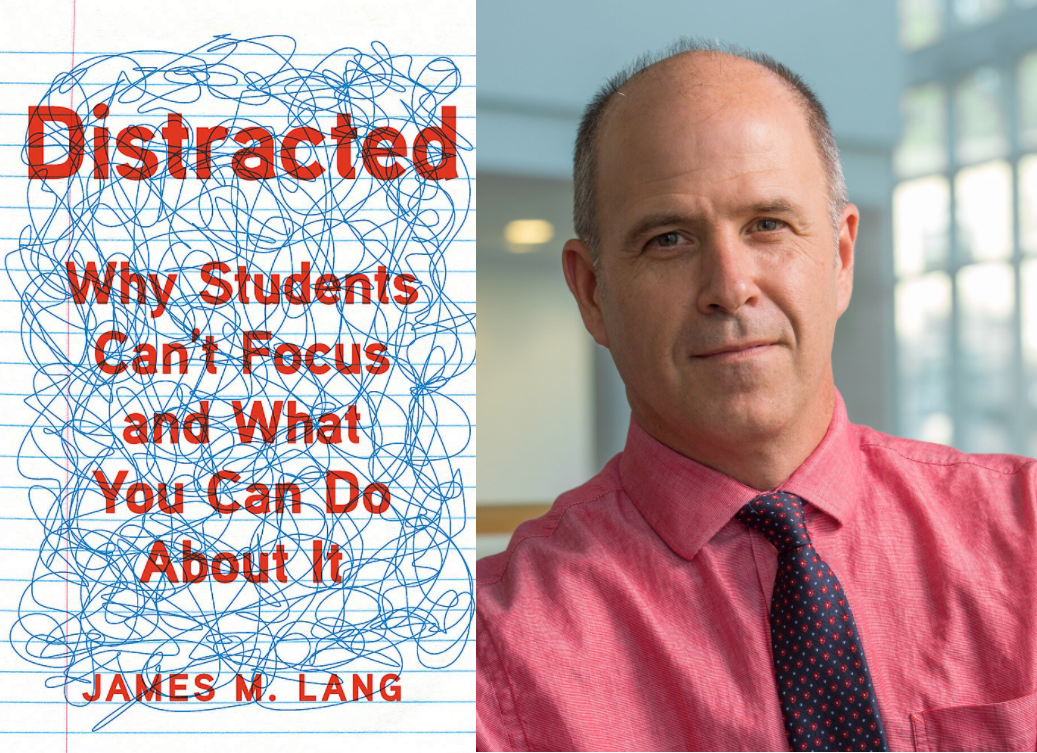

Book Review: Distracted by James Lang

By Julianne Morgan

I feel a little bit bad for James Lang, author of Distracted. He finished writing this book in February 2020 . . . a mere 3 weeks before the nature of human distraction fundamentally changed and his whole book became immediately obsolete.

I’m just kidding, of course. One, I don’t feel bad for him as I’m sure his book is still selling plenty of copies, and two, Lang himself (mostly) convincingly argues throughout the book that while we all perceive everyone to be more distracted than ever before, the nature of human distraction has never fundamentally changed - we are just as easily distracted now as our ancestors were in ancient Greek and Rome. So, his book is relevant, even during and (hopefully) after the pandemic.

Now I bet I know what you’re thinking -- our students, and even ourselves, are WAY more distracted now than in the past. I know I am. While writing this paragraph, I bounced from my email, to completing a task in Isidore, to responding to a coworker’s chat, to texting a friend, to looking up a song in Spotify, to rearranging a stack of papers on my desk, and those are just the distractions I can recall! (I’m blaming a hungry stomach for this - I wrote the rest of this article post-lunch). I think Lang would agree that we are indeed distracted by more things than in the past - but still the human mechanism of distraction is the same as it always has been in that “whenever we are attempting challenging cognitive work, distraction sings to us sweetly, beckoning us into easier and more pleasurable pursuits” (Lang, 2020, p. 9).

Lang’s claim is that distraction is simply more noticeable than ever before, not that it’s really happening more or less than before. For example, when I’m sitting in a classroom that doesn’t allow technology, I might more or less look like I’m focused on the lecture, but my mind could easily be wandering in a way that results in the same outcome as if I had my phone out - I’m not absorbing anything.

Prior to the publishing of Distracted, Lang did get the opportunity to add a new preface to the book that briefly considers how the pandemic has changed our ability to focus. This preface was clearly written in the early days of the pandemic, and I think he’d write that preface - and possibly even parts of the whole book - slightly differently now. The pandemic, I think, has altered our minds to be more geared towards multi-tasking, and in such a way that I really do think might present a challenge for teachers and learners alike in the post-pandemic (okay, mid-pandemic) classroom. It was one thing for students to completely zone out and not pay attention during the hybrid Zoom classes. We all became accustomed to (and somewhat disappointed by) that. It’ll be a completely different thing to see this distraction first-hand in our face-to-face classes.

So, what do we do about this? Should instructors ban technology in in-person classes? Is that even possible to do now that so much learning is happening online? Would banning technology in the classroom even make a difference (again, I think our minds wander WAY more than they used to -- or at least mine does, sorry folks)?

Here’s where Lang’s book is really useful, despite being written pre-pandemic. His foundational claim is that to overcome the challenge of distraction, “we need to turn our heads away from distraction and toward attention. Our challenge is not to wall off distractions; our challenge is to cultivate attention, and help students use it in the service of meaningful learning” (p. 10). It’s a bit pie-in-the-sky (also yes, I was just distracted by that phrase and had to look up its origins) of an idea, but Lang does present many practical and easy-to-implement strategies for cultivating attention throughout the book. Will the tips work for all types of classes, teachers, and learners? No. But, some of the tips might move the needle just a bit, and I think that might be the approach we need to take as we transition back to face-to-face learning. So, below are some of the tips I found to be the most convincing and easiest to try.

Build a Classroom Community

This is way oversimplifying the matter, but it’s easier to pay attention to someone who seemingly cares about you - even if it’s just pleasantries and small talk. Or perhaps the opposite is more true - it’s harder to be rude to someone if you know they care about you, even just a little bit. And, being the follow-the-social-norm creatures that we are, we are more likely to participate and engage in class if our peers are doing it, too. So, instructors should find ways to enhance the community of the classroom and keep it going throughout the semester, not just with introductions on day 1. Here are some tips:

- Arrive to class early and begin conversing with students on a personal level while you are setting up the classroom. Try to bring in other students to the conversation as they arrive so students begin to interact with each other (students talking to students is the magic that makes classroom attention happen).

- Learn students’ names and use them regularly. Encourage students to call each other by their names, too. Have a lot of students? Make name tents. Learn some of their names just to start the semester and continue making progress throughout. Practice learning their names using the Roster tool in Isidore.

- Solicit interaction from all students.

- If possible, rearrange the classroom for different kinds of activities. Novelty is a big part of attracting attention, so break up the monotony of the classroom-style layout and change to small pods for group work or any other configuration that matches the activity you are facilitating.

- Move yourself around the room. Again, not always possible, especially if teaching in a blended class. But if you are able to, teach in a different spot in the room each session for a few minutes. The students near you will be more likely to pay attention to you than when you were further away.

Cultivate Student Curiosity

I don’t know about you, but I can focus like crazy when I’m curious about something. I might find it challenging to be curious about . . . say, a calculus course (no offense to my math friends!), but if I were informed of how calculus is essential for determining the orbital dynamics of satellites to avoid collisions, then that just might get me to pay a little more attention. Again, there’s no one size fits all for cultivating curiosity, but here are a few strategies to try:

- Re-write your course description. What questions are answered by your class? Why are you teaching the class or subject? What made you passionate about this topic? How can students apply the skills learned in this class to real-world situations? Add this course description to your Homepage in Isidore and invite students to think broadly about what they will be learning.

- Start class with questions. Before diving into the content, present the questions and encourage students to attempt to answer them. At the end of the class session, present the questions again to see their answers had changed. This approach will whet their appetites to find the answers, and the reinforcement at the end will ensure the lesson sticks. Keep up with this practice intermittently throughout the semester.

- Incorporate questioning activities throughout the class period. Use the Quick Poll tool in Isidore to have the class answer questions together, or get more advanced with formal student response software like Socrative. Establish peer instruction activities where a question is posed, students consider the question individually and write an answer, students explain their responses to a peer, then have the opportunity to resubmit their answer if it changed based on the discussion. Do this on paper or use the Pre/Post tool in Isidore.

Change it Up

Lang shares a very scary study finding in Chapter 6: Student attention alternates between “being engaged and non-engaged in ever-shortening cycles throughout a lecture. Students report attention lapses as early as the first 30 seconds of a lecture, with the next lapse occurring ~4.5 minutes later, and again at shorter and shorter cycles throughout the lecture” (p. 135). He then backs this up with a lot of brain science that I won’t bother to regurgitate, but his point is that because our attention degrades over time, variety and change must be components of the classroom experience.

- Give breaks. Breaks aren’t really possible in 50-minute classes, but any class much longer than that should have a built-in break. Especially coming back from Zoom world where students could take many breaks without disrupting anyone, it will be critical to give students a chance to stretch, get water, or just permission to tune out in the longer classes.

- Vary course activities - but not too much. Too much variation can obviously introduce other kinds of distractions and also planning headaches. But, for a 50-minute class, plan on changing the format of teaching/learning about midway through the session. If your class is all lecture, conduct a few poll questions and discussion midway through. If your class is all group work, pause the class to deliver a mini-lecture. These changes will break up the monotony of doing the same thing for long periods of time, which results in more directed attention.

- Tell students the plan for the class session. At the start of each class, provide a brief agenda, e.g. lecture for 15 minutes, a group discussion about these questions, a break, and then a wrap-up lecture. This signposting helps students stay focused because they know what to expect and when.

Be Mindful and Compassionate

Mindfulness is the word in vogue right now! I don’t often get behind trendy words, but I really do think there is much to be gained by practicing mindfulness techniques. I won’t get into the approaches he shares because this blog is already way too long, but I do want to share what I think really is the most important takeaway from the book: be compassionate to your students and to yourself.

“When we come into the classroom, everyone arrives trailing clouds of distraction from whatever prior activities and thoughts have been occupying our attention. We might be obsessing over a text from a loved one, indignant about the latest outrage perpetrated by our least favorite politician, or thinking about the lunch we just ate or the one we’ll be having after class. Students are talking to their peers, swiping through their Instagram feeds, and worrying about their dwindling bank accounts. From this state of minds in motion, we expect students to grind the spinning wheels to a sudden halt and focus on string theory, or institutional racism, or existentialism. We should not wonder that they have difficulty drawing the class into focus—or that we have the same difficulties.”

And again, this was pre-pandemic writing.

Our worries and anxieties have compounded, and younger students especially have now had 1.5 years of being basically conditioned to learn while multitasking. Can you put yourself in 18-year-old shoes and even fathom what it must be like to try to learn? I’m so grateful that I was born before smartphones, laptops, and (accessible) internet because I do have an inkling of what it is like to try to learn without all this. These kids really don’t, and social media and social relationships feel so much more urgent and pressing than ever before. I know we should try to help students overcome or healthfully address these challenges, but I just don’t really know how possible it is when it’s become such a critical component of living. I’m reminded, too, of Dr. Tiffany Taylor Smith’s and Dr. Leslie’s Picca presentation at the Teaching and Learning Forum this past year. Recognizing our own distracted lives and bringing those distractions honestly to the forefront actually increases inclusivity in the classroom. We are all living messy lives, and we do nothing but perpetuate false perfection by pretending otherwise. So, I truly advocate for everyone to try to be compassionate with students, with each other, and with ourselves. We will learn how to teach and learn in this changing environment. It will take time, but we will get there, and we’ll do it together.

Final Thoughts

The last thing I want to share is that I read this book with a fabulous group of staff and faculty during the Spring 2021 semester in book read sessions facilitated by Dr. Michelle Pautz. I greatly enjoyed our discussions together, and I advocate all to sign up for any future book read sessions that are offered because it really does help to talk these things out. Dr. Andrew Rettig from the Department of Geology summarizes that sentiment perfectly: “Mostly, the book helped me to trust many of my own instincts and methods to help with attention in the modern classroom. But I think it was most beneficial to read the book with a group of professors to listen to different perspectives and ideas for attention in the classroom.”