Blogs

Charles I, the Controller of Catholicism

By Emma Donnelly

One 17th-century Bible can illuminate how King Charles I of Great Britain used Catholicism as a means to achieve territorial unity and dominance during a time of religious turmoil and violence.

Imagine you had the power to suddenly enter the world of any book you read. You could see for yourself the true context behind the written words and discover things you wouldn’t find in its pages. Suddenly, the book would take on a whole new meaning; you’d be connected to it in an almost supernatural way. It sounds like something out of a fairy tale, but the truth is, some books have meanings that transcend the words on the pages and provide us with a connection to a different world — or a different time.

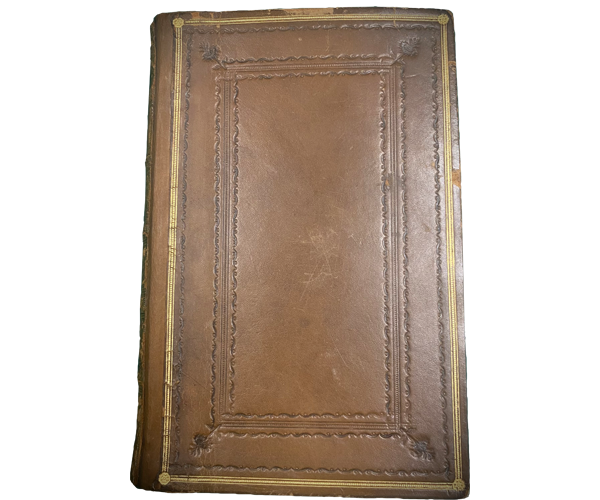

One such treasure, a New Testament Bible published in 1638, has recently undergone conservation work to become more accessible to classes and researchers in the Marian Library at the University of Dayton. The Bible was printed by the Stationers Co. in London under the reign of King Charles I. Before conservation, it was largely intact, although it had significant damage to the binding, back board and spine. After the relining of the spine with cloth and a hollow tube, reattachment of the back board and rebuilding of the binding, the story behind this Bible began to come to light. It soon became clear that the Bible had played a part in King Charles I's plan to gain power and control of Europe.

A Bible for the masses

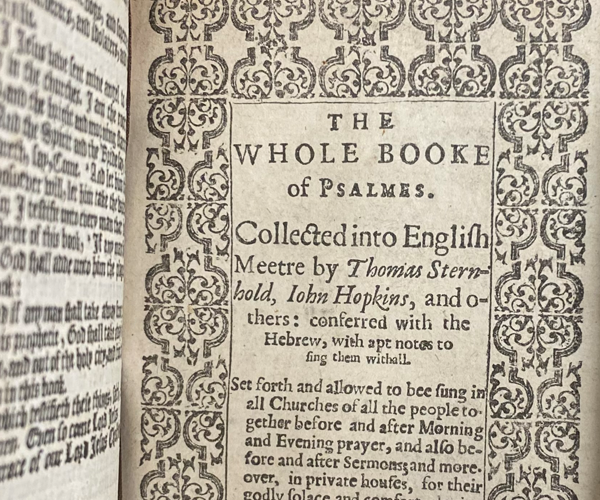

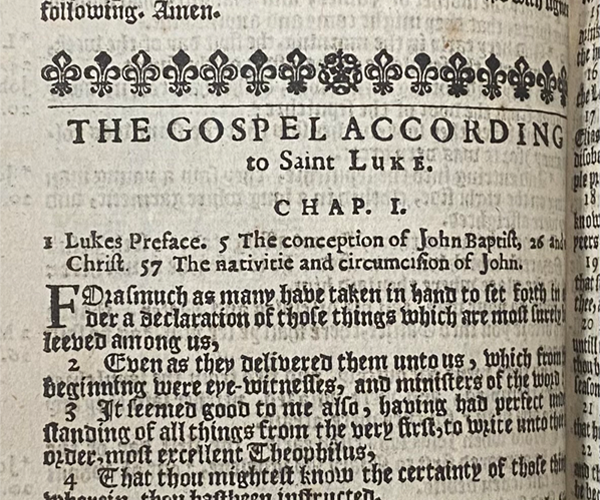

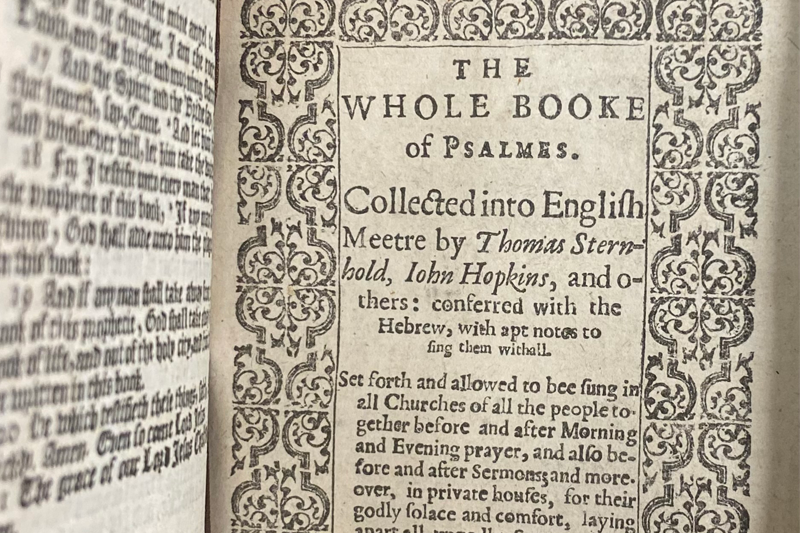

The Bible is small in size, and its paper, ink and calf leather binding were commonly used in printed Bibles of the 17th century. Inside, it contains the Gospels and books of the New Testament as well as a list of psalms and prayers for everyday activities — including prayers of thanksgiving and morning and evening prayers for use in private homes. These all indicate that this Bible was printed for everyday use of a literate person, though not a noble. Inscribed on the last page of the Bible are the words "printed for the Company of Stationers." The Stationers Co. was a printing company that received a Royal Charter in 1557 after the invention of the printing press made mass production of books possible. The workers of the Stationers Co. registered the titles of books they printed with the company to ensure they weren’t made available from outside competitors, which led to the earliest establishment of copyright laws.

Power of the press

The context behind the publication of this Bible also helps us understand the role it played in a global picture. In 1638, Europe was in the middle of the 30 Years’ War, a period of violent religious wars between territorial religious factions. Charles I saw an opportunity to do what no one had been able to do yet: merge religion and state into one under his rule. Charles I, a devout Roman Catholic viewed with mistrust by many English Protestants, pressured his subjects to practice a Christianity highly influenced by the Roman Catholic sacraments, rituals and beliefs. This was a bold move considering England’s diverse religious history, but Charles I had an ingenious weapon: a perfected and proficient printing press.

Although the printing press was invented nearly 200 years earlier, its true power became apparent during the Renaissance and the Reformation. It allowed for the faster and wider spread of ideas, increased public access to books and increased literacy rates among the poor. Rulers attempted to harness its power and appointed companies such as the Stationers Co. as “royal printers,” meaning they were dedicated to printing and distributing messages regulated by the king. For Charles I, the printing press was the link between control of religion and control of state. He took advantage of the opportunity and authorized the Stationers Co. to print Bibles like this one, which sought to integrate Catholic practices into the everyday lives of his citizens. In this way, Charles I not only facilitated the spread of his religion, but used this power to unite his subjects under him (spoiler alert: A rebellion later ended with Charles I’s execution).

A lesson from history

The story behind this Bible sounds like something straight out of a dystopian novel: An autocratic ruler abused a holy book to unjustly consolidate his own power. But this Bible also symbolizes hope. By shedding light on the injustices of the past, perhaps it will ignite a spark in faithful people to speak up in God’s name against the injustices of the present.

— Emma Donnelly ’26 is a history major and a student employee in the Marian Library.

Note from the Marian Library Director: This conservation project was generously funded through a gift by Larry Spieth.