Blogs

The Holy Fool

By Vincent Miller

“God has chosen what the world holds foolish so as to embarrass the wise.”

1 Corinthians 1:27

The figure of the fool appears across many cultures and in many forms. Courtly fools, who entertained rulers, were common in Europe, the Middle East, India and China. Hernán Cortés encountered fools in the Aztec court of Montezuma. Courtly fools provided both entertainment and a counterpoint to the ritual and flattery of courtly speech. Fools were free in a way that others were not to challenge and mock others, including the ruler. Long before modern political freedoms, the fool enjoyed a freedom of speech that courtly language denied to anyone save the monarch.

The court jester lampoons the sycophant. He is the one who can make fun of the king for letting his people starve, the one with the power to bring the message of the mood of the common people before the king. A clown can speak the truth to power and still live.

Fools came from all strata of society. Some were educated members of the aristocracy. Historian Beatrice Otto notes the global history of fools being drawn from people with developmental or visible physical disabilities. In Christian and Islamic cultures, the care of such persons was both a responsibility of elites and a display of their prestige. People with dwarfism were likewise active in courts around the world.

Fools excelled in many skills from acrobatics to music and verbal repartee — both mocking learned language and excelling at speech and verse. The figure of the courtly fool overlapped with — and shared the skills of — traveling entertainers in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The minstrel, troubadour, acrobat and jongleur performed music and song, storytelling, juggling and tumbling. The author G.K. Chesterton distinguished the jongleur from the troubadour: Troubadours sang of idealized romantic love, while jongleurs provided “comic relief” with humor, acrobatics and juggling. The jongleur knew a freedom that “almost amounted to frivolity.”

St. Francis of Assisi bridged these European traditions and more ancient traditions of the “holy fool.” A wanderer who preached the love of God and expressed his devotion to “Lady Poverty,” he drew upon the traditions of the troubadours, but he described himself and his followers as more humble “jongleurs for God.”

Holy fools appear in vastly different religious traditions across times and cultures. The Cynic philosophers in ancient Greece exemplify one aspect of this way of life. They dressed poorly (if at all), disdained convention with their scandalous behavior and challenged the powerful. The Cynics influenced early Christian asceticism. Some scholars find traces of Cynic philosophy in Jesus’ preaching in the Gospels.

Similar figures are found in ancient Hebrew, Buddhist and Taoist traditions. All challenge convention, skewer pretension and witness to a more profound moral or spiritual vision. The rotund visage of the 10th-century Buddhist teacher 布袋 Budai, known as the “the laughing Buddha,” is immortalized in countless statues. His name means “cloth sack,” which he is often portrayed carrying on a stick over his shoulder. He was a poorly dressed wanderer without possessions, fond of food, inclined to humor and beloved of children.

Early Christian monasticism manifests another dimension of the holy fool — the holy person who seeks to avoid honor and vainglory by feigning mental illness or even immorality. A fifth-century Egyptian monastic text provides an early example: A nun considered mentally ill by the rest of her monastery lives, often abused, in the kitchen doing menial labor, surviving only off the scraps she cleans from the dishes. A revered monk, inspired to visit the monastery, asks to speak with all of the nuns. When she is left out, he rebukes the others for their ignorance and refuses to leave until he receives her blessing. Her holiness revealed, she flees the monastery and is never heard from again.

In many cultures, the holy fool was near to another figure: the madman or madwoman. The 12th-century Sufi Muslim thinker Ibn ‘Arabī compared the mystic’s experience of God to the natural loss of reason among the mentally ill. God could speak in the voices of the mad.

The profundity and power of the fool has faded in the modern era — eroded on multiple fronts. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Enlightenment transformed politics, replacing the propriety of courtly life with free speech and public debate. Modern medicine medicalized madness into mental illness — no longer a potential source of wisdom, but a set of symptoms to be managed. Finally, in the 19th century, the broad mission of the troubadour and jongleur was reduced to the staged performance of the clown.

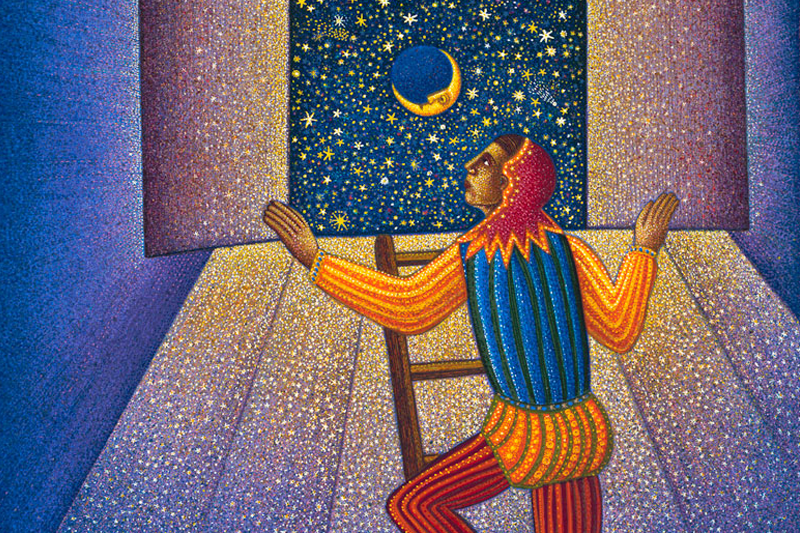

Reverence for the fool and longing for their subversive power, however, lives on in art and literature such as Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Gimpel the Fool” and the character Otsu in Shusaku Endo’s novel Deep River, the paintings of Georges Rouault and the prints of John August Swanson.

— Vincent Miller is the Gudorf Chair in Catholic Theology and Culture at the University of Dayton.

View artworks related to holy fools while you learn about the story of the humble Juggler and his gift to the Blessed Virgin Mary when you visit the Marian Library’s Christmas exhibit Juggling for Mary: Vocation, Gifts and Performing for Our Lady.

Image: Jester (detail) by John August Swanson, hand-printed serigraph (35 colors), 2001

Sources:

Billington, Sandra. A Social History of the Fool. United Kingdom: Faber & Faber, 2015.

Chesterton, G. K. St. Francis of Assisi. United Kingdom: Dover Publications, 2008.

Dols, Michael Walters. Majnūn: the Madman in Medieval Islamic Society. United

Kingdom: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Forman, Mary. Praying with the Desert Mothers. United States: Liturgical Press, 2005.

Otto, Beatrice K. Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World. United

Kingdom: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Peacock, Louise. Serious Play: Modern Clown Performance. United Kingdom: Intellect, 2009.

Welsford, Enid. The Fool: His Social and Literary History. United Kingdom: Faber, 1968.