Blogs

Rosary Revelations: The History of Prayer

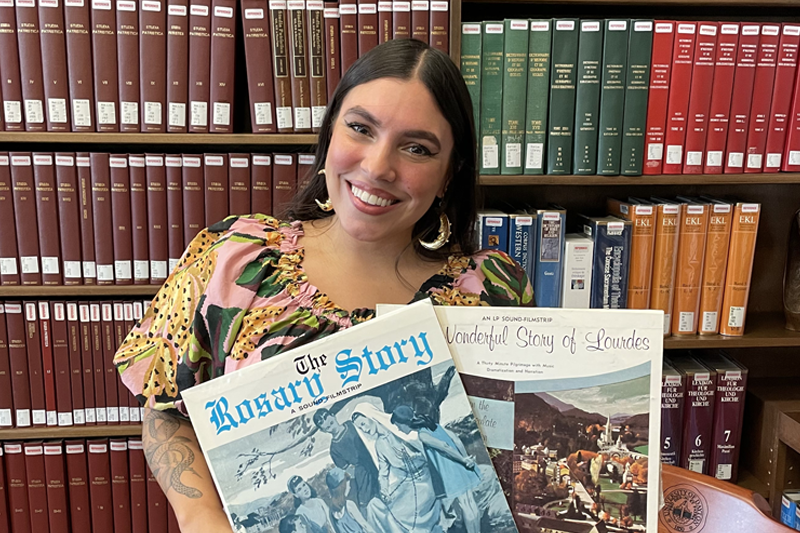

By Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada

In 2019, the Pope’s Worldwide Prayer Network debuted its Click to Pray eRosary, a bracelet made of black agate and hematite beads with a “smart cross” featuring Bluetooth technology and a lithium-ion battery. The sleek dust- and water-resistant wearable device doubled as a fitness tracker. Aesthetically, it was a rosary for the athleisure moment. I was fascinated by the press coverage. FastCompany called it a “Fitbit for your spiritual health,” and many saw this as the Vatican’s attempt to be savvy, keep up with the times and attract millennials. This rosary was one of the inspirations behind my book project: Reinventing the Rosary: Innovation and Catholic Prayer.

While the rosary is an iconic Catholic object — typically made of a crucifix and beads on a chain or string — it has gone through dramatic redesign and reimagining, driven by technological transformations of the 20th and 21st centuries, to better fit the demands and desires of modern life. The material history of the rosary reveals how American values of efficiency, convenience, productivity and entertainment helped shape the objects and practices of prayer in the United States. It explores how new media — such as radio, television and film — and technological transformations — in plastics, microchips, virtual reality and app development — transformed the experience and potentialities of prayer.

This past summer, I was fortunate to receive the inaugural Visiting Scholar Fellowship at the Marian Library to support my research for the book. The Marian Library is full of treasures — my favorite kind of treasures: the material culture of Catholic devotion. In its collection, I pored through boxes of carefully cataloged rosaries. There were electronic rosaries; rosaries designed especially for steering wheels and gear shifts; and rosaries made from surprising materials — such as peach pits and horse hair. As a scholar of material culture and embodiment, handling these objects was important. Feeling the size, temperature, texture and even smell (some scents were pleasant, others were rancid!) of the beads is essential for understanding the sensory dimensions of prayer.

The collections at the Marian Library illustrated clear links between consumer culture and Catholic devotionalism. For example, the archivists and staff brought out a record player and allowed me to listen to The Rosary Story. Originally marketed as a “A Multi-Media Way To Dramatize the Effectiveness of THE ROSARY STORY,” the record came with two filmstrips and a filmstrip viewer. This new “audiovisual” prayer from 1962 “dramatized” the rosary and hoped to create an immersive form of prayer. In the archive, I could explore how praying the rosary did not just feel like touching beads; it could also feel like gently placing the needle of a record player down on vinyl and adjusting the plastic knobs of the player. As the rosary was remediated and shaped by the forms and materials of popular culture, entertainment and leisure, the soundscape of prayer was also changing.

In addition offering a view into the lived, tactile, bodily dimensions of Catholic devotion, the Marian Library provides opportunities to dive into the organizational lives of lay Catholics. The newsletter collections of Our Lady’s Rosary Making Club, which spanned the 1950s through the 1980s, revealed that creating rosaries with beads and wire with pliers in hand was itself a form of devotional practice. Across the country, Catholics gathered to make rosaries with their own hands for distribution across the globe. Through their craft, they imagined they could touch the lives of faraway peoples and places. The organizational materials, rosary parts catalogs and how-to guides offered a fascinating glimpse into the practical, tactile and communal dimensions of Catholic devotional life.

With the library’s expansive Sutton File, which features news clippings on all things Mary, I spent days exploring news stories and advertisements. In those files, I was able to explore the impact of radio, film and television on prayer and understand how these mass media forms were transforming and shaping the imaginative possibilities of prayer and meditation and how increasingly the rosary’s power and efficacy came to be understood through modern media. Across all of these materials, I was exploring how making, listening, touching and seeing were all essential to the sensory and bodily experience of prayer.

Poring through the stuff of prayer and print culture of mid-20th-century devotionalism and the well-curated collection of Catholic press clippings continued to reveal to me how the history of prayer is also a design history and a media history.