Blogs

Anichini’s Rome

By Eve Wolynes

Dante was not the only building block of Italian identity that inspired artist Ezio Anichini’s work. The infant state looked to other influences to find unifying footing, present in both Italian heritage and Anchini’s art: imperial Rome, which had long influenced the peninsula. That influence only grew stronger as the nation grappled for stability and unity.

As early as the Middle Ages, many individual Italian cities formed their own governments called “communes” during points of political reformation and upheaval. They took to tracing their foundations and origins back to famous Greek and Roman mythological heroes as a tool for political legitimacy — most popularly Aeneas, the legendary founder of Rome in Virgil’s Aeneid. These city-states also groped around for alternatives such as Janus, the Roman god of beginnings, time and transitions; Romulus and Remus, the other legendary founders of Rome, a pair of twins nursed by wolves; and occasionally more obscure figures like Antenor of Troy, a minor figure in the Trojan War.

Five hundred years later, national unification created another moment of dramatic political transition, and Italians turned once more to the distant empire as a bedrock of national identity. Rome had united the peninsula before, and now it was united once more. From there, Italian unity and nationalism flowered into Italian conquest: The rhetoric of Imperial Rome became justification for a new imperial Italy in the 1930s. Mare nostrum (“our sea”) — the term used in Rome for the entitlement to control of the Mediterranean and imperial expansion — was taken up once more, this time by Prime Minister Benito Mussolini and other nationalists to justify Italian colonialism and expansion in North Africa over 2,000 years later. This was a testament both to the lingering impact of history and to the different ways people have used the past to define and understand the present.

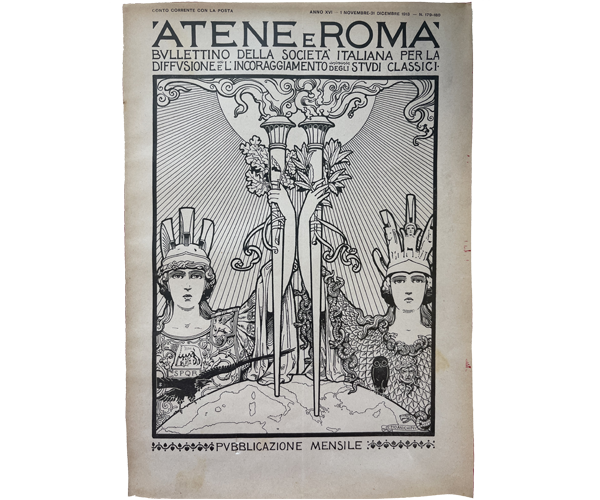

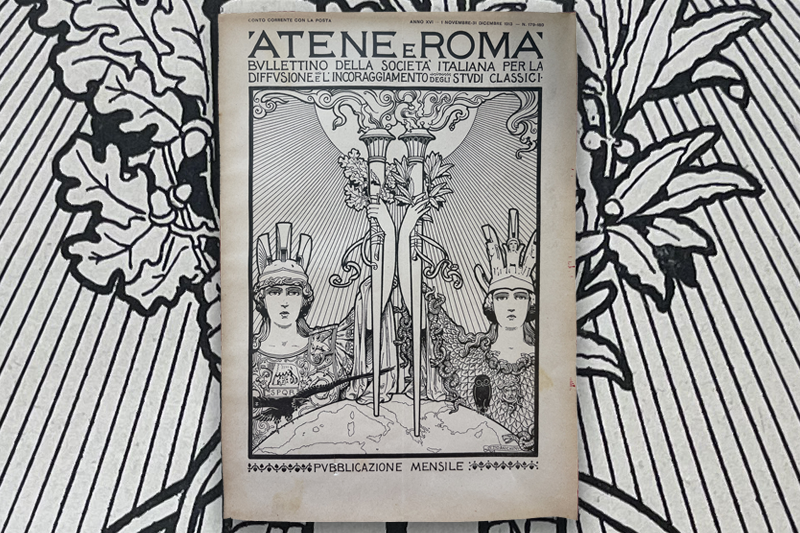

Anichini’s art shows clear elements of the importance of classical Roman heritage in Italian culture. For the magazine of the Italian Society for the Diffusion and the Encouragement of Classical Studies, Anichini illustrated a cover pairing the ancient goddess Roma — an embodiment of the Roman state and, implicitly, the modern Italian state — together with Athena, goddess of wisdom, war and Athens, overlooking the Mediterranean. The image pairs together ancient Rome and ancient Greece to illustrate their dominion over the Mediterranean Sea just as mare nostrum ordained.

This connection between national identity and classical heritage also manifested in Anichini’s illustrative work retelling classical stories as children’s books. Children’s books form the foundations of national identity by serving as tools of instruction: They teach children the myths and stories of their cultures and societies; teach them their values (often in a simplified way); and model how to understand the world around them. In Le avventure di Enea: Narrate ai giovani (The Adventures of Aeneas: Narrated to Children), by Giovanni Vaccari, Anichini integrated the styles of ancient Greek vase paintings to retell Aeneas’ foundation of Rome, rendering the national origins of Italy into bite-sized, easily understood pictures for children, beginning their own formation of their Italian identity tied to a classical heritage.

Visit the Marian Library and A Vision of Art and Faith: The Litany of Loreto and the Work of Ezio Anichini (1886-1948) to see a variety Anichini's work across many themes, including Litany of Loreto images from the Marian Library's collections.

— Eve Wolynes is a library assistant in the Marian Library.