Blogs

Anichini’s ‘Divine Comedy’

By Eve Wolynes

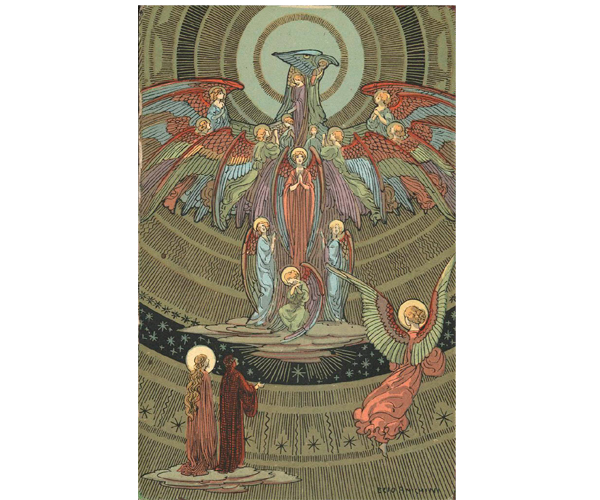

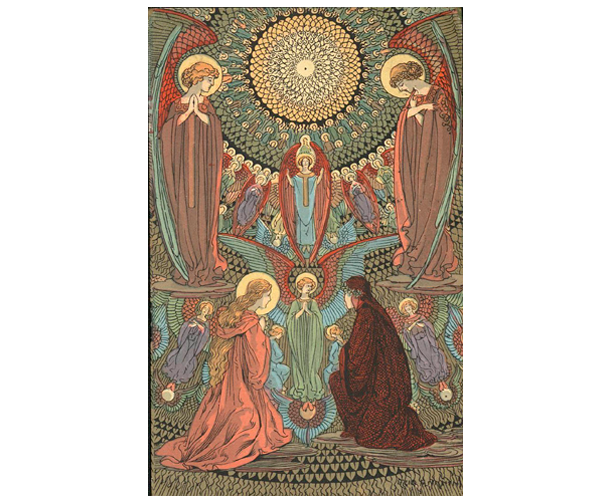

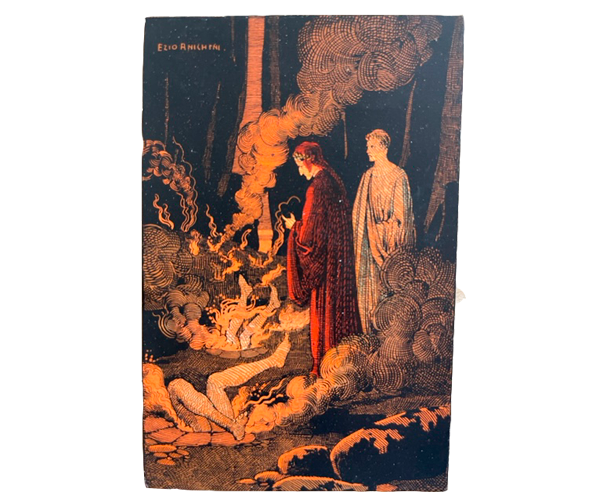

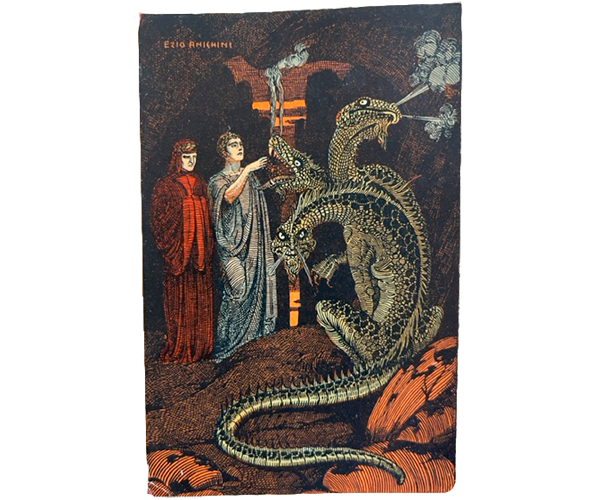

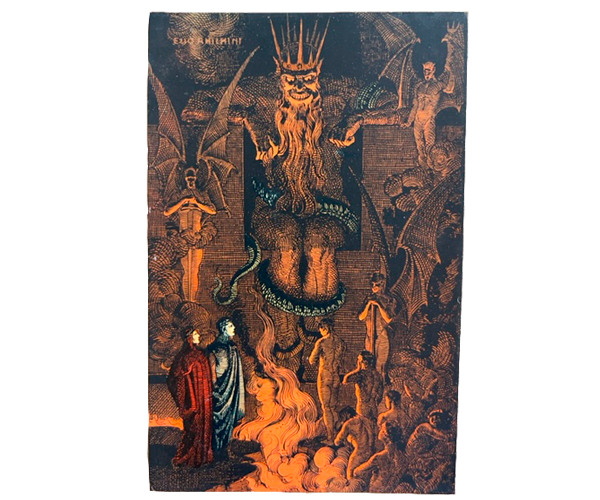

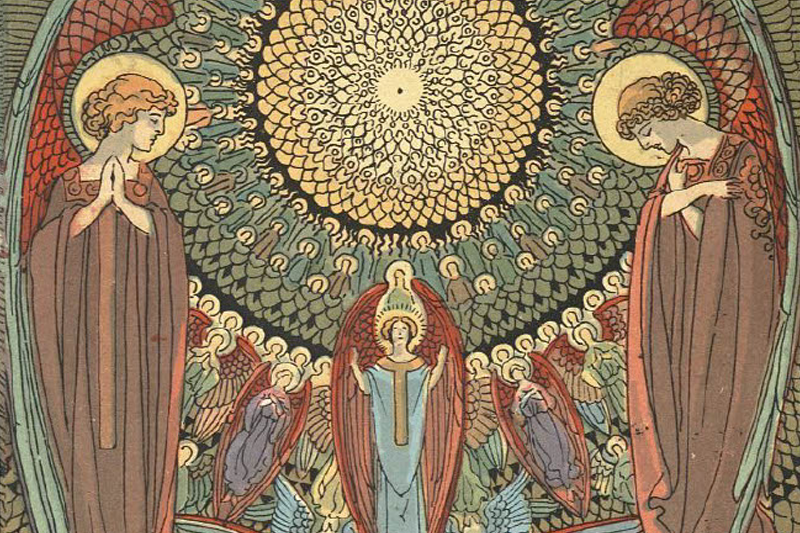

As Italy prepared to mark the 600th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri in 1921, it commissioned the up-and-coming artist Ezio Anichini — whose works are presently on exhibit in the Marian Library — to produce 52 illustrations for a new edition of Dante's most famous work, The Divine Comedy (La divina commedia).

Anichini's vivid, evocative images — some terrifying and grotesque, others ethereally beautiful — depict all three parts of Dante's allegorical journey in La commedia: hell, purgatory and paradise. In it, Dante witnesses God as a nonphysical embodiment of light and love and instantly understands Christ and the mystery of divinity.

Anichini’s task with the illustrations went beyond celebrating Dante's status as a cultural icon; Italy’s additional intent with the new edition was to unify Italians both politically and culturally, and to build national pride for the young country, which had been established merely 60 years earlier.

‘Father of the Italian Language’

Today, Dante’s Divine Comedy is arguably most famous as a work of faith — but in Anichini’s lifetime, Dante’s importance to Italian identity lay in politics, patriotism and language. Italy the state was practically an infant, having only formed (through many rebellions, conquests and revolutions) in 1861. Languages unite people, but without a common language, the country remained linguistically fragmented. Italians even in neighboring cities often could not understand each other’s local dialects. Dante’s poetry, however, rose as a universal point of pride. His De vulgare eloquentia redeemed and celebrated the poetic prowess and beauty of Italian languages in an era when anything but Latin was often derided as brutish. As a result, Dante was eventually heralded as “the father of the Italian language.”

Linguistic Legacy

Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio — considered the “crowns” of Italian literature — wrote in the Tuscan dialect. Their works were read so widely across the peninsula and beyond it that their “Tuscan” became synonymous with “Italian” even before political unification. All educated elites throughout the peninsula could read (though perhaps not speak) his “Italian.” Dante’s influence on the peninsula was so strong that when Italy unified, his Tuscan Italian became the official language. Even after 700 years, today’s Italian is virtually identical to Dante’s Tuscan.

Political elites throughout the 19th and 20th centuries called upon Dante’s work to help them define Italian identity and patriotism through official festivals and celebrations. The 1865 celebration of the 500th anniversary of Dante’s birth brought 50,000 attendees — including the king of Italy — to see a new monument to Dante in the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence. Between 1861 and 1930, government-funded statues, towers and town squares — all built in Dante’s honor — sprung up across the continent in Trento, Mantua, Genoa, Rome, Catania, Grosseto, Pisa and Verona.

Without words or language — “Tuscan” or “Italian” — Anichini demonstrated the medieval author’s continued significance as a unifying figure in Italian identity into the 20th century.

See Anchini’s Illustrations

If you find this topic interesting, visit the Marian Library’s current exhibit, A Vision of Art and Faith: The Litany of Loreto and the Work of Ezio Anichini (1886-1948), to see more of the artist’s work revolving around the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Italian identity of his times.

— Eve Wolynes is a library assistant in the Marian Library.