Blogs

A Garden for La Virgen de Guadalupe

By Yamilet Perez Aragon

In an unexpected way, the timing for working with the John Stokes and Mary’s Gardens Collection during my OhioLINK library internship perfectly aligned with the topics I was working with in my sustainability capstone. It was interesting to read about how the initial idea for Mary Gardens was to make the information available through volunteer lay initiatives. I saw a similar approach to stewardship at Mission of Mary Cooperative — the local urban farm that my class’s group project is partnering with. While I was learning at the library about how gardening creates avenues for stronger devotion and personal connection to Mary and individual faith, I was also learning from Mission of Mary about how gardening creates stronger independence and empowerment for low-income people in urban communities. My view of gardening expanded as I connected these two experiences. I realized that even as development expands and creates more division between humans and the natural land, we can still create urban planning that includes possibilities for transforming uncultivated green space to have more sustainable systems where individuals can connect with the land and their spirituality, as well as share with neighbors for deeper community unity.

Working on the creative project part of this rotation also perfectly aligned with the topics I was learning about in my History of Art Activism class. As I was looking for ways to portray a visual Mary Garden that connected to other interests of mine, I was inspired by the Chicano murals and paintings of Yolanda Lopez and Yreina Cervantez who were expressing similar concepts as those I wanted to include.

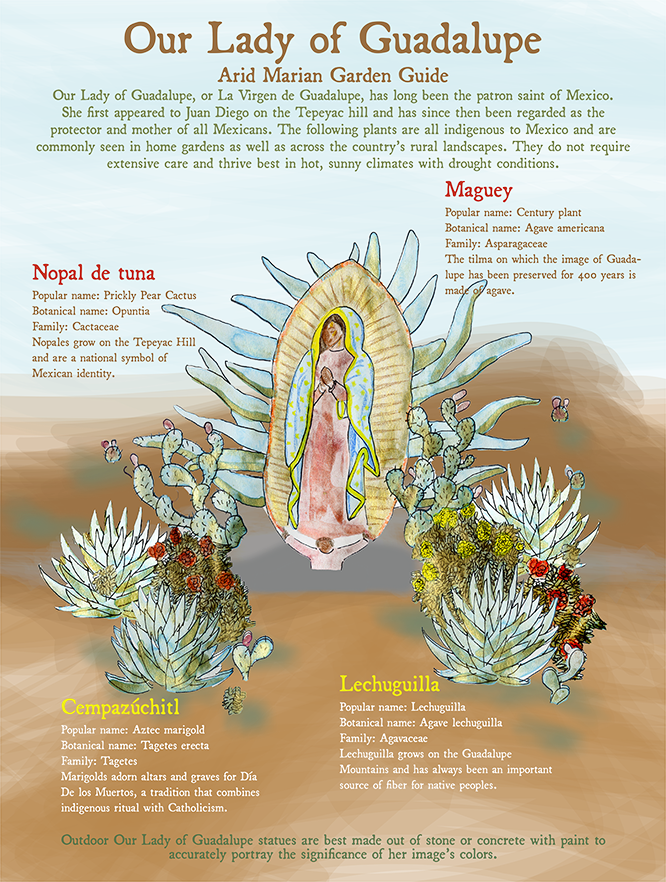

La Virgen de Guadalupe

Our Lady of Guadalupe, or La Virgen de Guadalupe, has always been known as La Virgencita to me. Growing up, she was everywhere around me — in frames around my house, on jewelry around my neck, on TV every day at 6 p.m. through La Rosa de Guadalupe, a telenovela-like series where every single episode involves someone being touched or moved by Our Lady through a wind and the appearance of a white rose. Despite being really cheesy, my mother and I have watched this show almost every single day since I was little, singing along in the end credits to the most famous song dedicated to her, La Guadalupana. This same song has been sung by all my relatives and most of Mexico every Dec. 12 for Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe.

Today, being 1,000 miles away from my parents in Texas, and another 1,000 from the rest of my family in Mexico, I can turn to Our Lady of Guadalupe as a way to connect to them. If I pray the rosary, it brings me closer to my mother and grandmother, knowing they are out there praying it too. My parents left their families to come to this country and build a better life, yet all my mom does is worry for me when I have done a similar thing to improve our family’s opportunities. She prays for me to Our Lady of Guadalupe, and in knowing that, I know that La Virgencita protects me and has my back.

An Artistic Guadalupe Garden

When choosing what plants to include in my Guadalupe garden, I was putting together various possibilities from many different places. I was looking at the Stokes planting lists, multiple physical materials in the Marian Library, and many online resources. However, when visualizing what this garden could really look like, I found myself envisioning more and more plants that had been present in my own life. In the end, this is what I felt the most connected to. It was interesting to see many of the plants that were popping up in my academic research were also plants that I had learned about through my grandparents’ spirituality, without realizing the wisdom and devotion present in those casual teachings.

This was the case with the agave varieties maguey (century plant) and lechuguilla, which were pleasant surprises to see on my Ohio computer screen while I was so far from home. There, agave grows everywhere and was always pointed out and appreciated by my family.

El nopal (the prickly pear cactus) was an extra special choice for me. I chose it not only because of the significant symbolism it carries as an identifier of national Mexican culture, or because it grew on the Tepeyac — the place where Our Lady of Guadalupe first appeared to Juan Diego — but because for centuries, it has been a staple food that has fed millions and kept people alive, including my own family, who in poverty ate it along with only beans, rice, and maize. As a protecting mother who watches over us, La Virgen de Guadalupe gave us this plant for nourishment. When feeling isolated away from culture, eating nopales is another way I connect to familiarity and reminders of the blessings she brings.

— As an OhioLINK Luminaries Intern, Yamilet Perez Aragon ’23 participated in rotations in several departments across the University of Dayton Libraries during the 2021-22 academic year.

— As an OhioLINK Luminaries Intern, Yamilet Perez Aragon ’23 participated in rotations in several departments across the University of Dayton Libraries during the 2021-22 academic year.