Blogs

Stone, Paint, and Wood: Survival Amid Destruction

By Eve Wolynes

In times of strife and conflict, faith and devotion often serve as emotional bastions for the faithful. On a terrestrial level, churches often do the same during times of war. On March 2, the Assumption Cathedral of Kharkiv, Ukraine, built in 1659, offered itself as shelter for all Kharkiv residents until a missile struck it, shattering its historic stained-glass windows but protecting those within from harm.

(Photo is of the Holy Spirit Chapel of the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary of Lviv, Ukraine with artwork by painter Petro Kholodny and sculptor Andriy Koverko.)

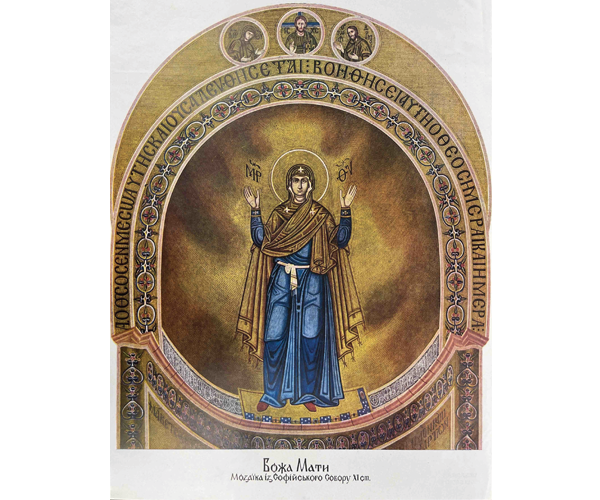

The destruction of art and architectures of faith is not always the tragic byproduct of warfare; it can also be a wanton and cruel tool to silence ideologies contrary or subversive to those in power. Consider the work of Ukrainian artist Petro Kholodny. The Holy Spirit Chapel of the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary of Lviv, Ukraine houses a rare surviving piece of his artwork, an iconostasis depicting Mary at a writing desk and holding a scroll — objects more typically associated with prophets and apostles rather than the Blessed Mother.

Kholodny was an artist — but he was also involved in the 1917-20 fight for Ukrainian independence from the Russian Empire and was the deputy minister of education under the Ukrainian National Republic until 1920. He went into exile after the Soviet victory and ultimately settled in Lviv, then part of Poland. There, he continued to produce religious art for churches, largely inspired by traditional Ukrainian styles that combined folk art and Greek Byzantine iconography.

Thanks to his alignment with Ukrainian independence, however, many of his works, both secular and spiritual, were destroyed during Soviet occupation of Lviv for allegedly having “ideologically harmful” Ukrainian nationalist elements. The Holy Spirit Chapel, which provides valuable artistic, religious and architectural representation of the cultural heritage of Ukraine and its Byzantine roots, could also have become a casualty of the political censorship, violence and destruction of art and artifacts in the wake of Soviet attempts to erase culture and identity. A German bomb struck the building in 1939, and the Soviet state closed the seminary and and seized its property in 1944.

The building reopened as a theological seminary shortly after the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine in 1990, and today, it stands as a testament to the resilience that both architectures and institutions of faith can embody in difficult times.

Now Lviv plays a similar role for refugees from eastern Ukraine that it once played for Kholodny, taking in some 200,000 displaced Ukrainians and serving as a safe haven against war — for the time being.

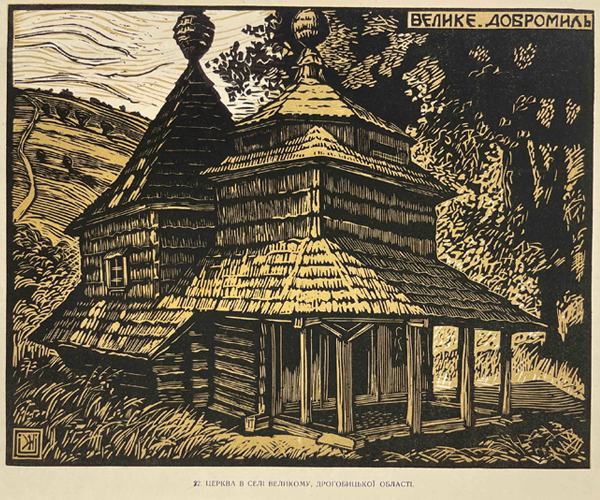

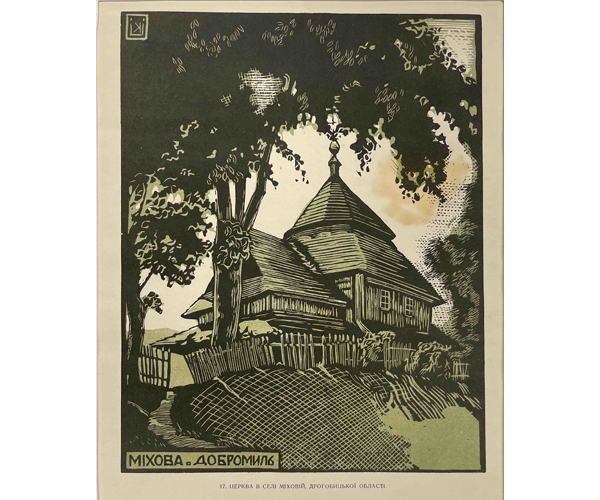

Other examples of Ukrainian architecture

Elsewhere in our collection we can see further examples of Ukrainian architecture’s complex and intersecting qualities: its material vulnerability; its enduring strength for providing safe haven and refuge; and its embodiment of the varying cultural heritages of the Ukrainian people. In prints depicting the wooden Churches of the Nativity in Velyke and Mikhova, Ukraine, we see an architectural style that reflects rural peasant culture with origins in the 11th century, rather than the wealthier — and sturdier — constructions of stone we normally associate with urban church architectures that have survived the centuries. While the examples here date to the early 20th century, the oldest wooden church that survives, the Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, was built in 1502. Because of their vulnerability to fire and decay compared to stone buildings, fewer than 500 wood-construction churches in Ukraine built before 1800 survive today. On March 8, Russian shelling destroyed an 1862 wooden church near Viazivka that had withstood time and threats of fire for over 150 years.

— Eve Wolynes is an intern in the Marian Library working toward her master’s in library and information science from Kent State University, specializing in cultural heritage stewardship and preservation.