Blogs

Bartolo Longo and Our Lady of the Rosary

By Henry Handley

Oct. 5 is the feast day of Blessed Bartolo Longo (1841–1926), described by Pope John Paul II as “a true apostle of the Rosary” in Rosarium Virginis Mariae. After abandoning spiritualism, a 19th-century movement seeking to communicate with the dead through mediums and seances, Longo reported hearing the Virgin Mary’s voice calling him to promote devotion to the rosary. He and his wife did just that — and reinvigorated Catholic devotion in Pompeii, Italy, and around the world. His story isn’t just a testament to the popularity of the rosary, however; it’s also a story about the role of the Catholic press and charity in the wake of the Industrial Revolution.

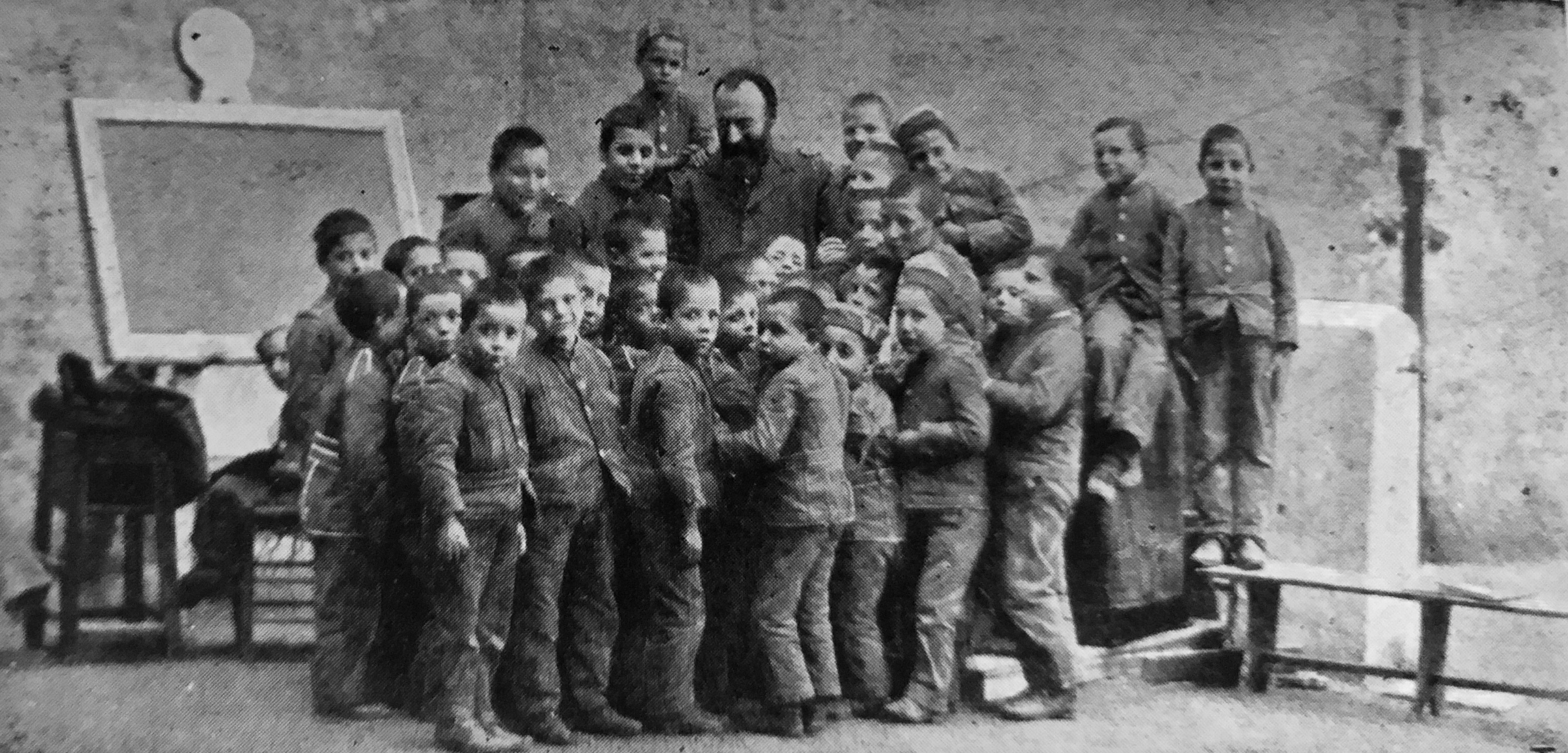

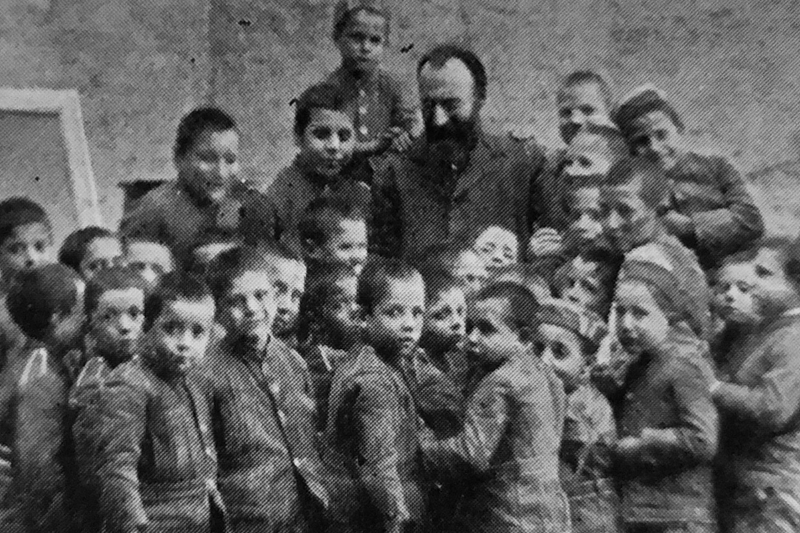

Longo organized numerous institutions in Pompeii in honor of Our Lady of the Rosary. Besides the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, he also founded schools, a volcanological observatory near Mount Vesuvius, and a printing office at a home for boys with imprisoned parents — variously credited in its published works in English as the Editing School of the Sons of Convicts or the Pontifical Printing School for Prisoners’ Sons. The school’s publications were a major vehicle for promoting the rosary around the globe. Longo wrote novenas of petition and thanksgiving that were printed in over 15 languages; the Marian Library holds versions of popular works in the original Italian as well as in translation in English, French, Hindi, Serbo-Croatian, Spanish and the constructed language Volapük — over 70 of Longo’s works in all, as well as decades of issues of the periodical Il Rosario e la Nuova Pompei, which Longo founded in 1884 and is still in publication today.

Though Longo’s life is well documented, especially through his writings, the lives of the boys who worked at the printing school are now all but unknown. In History, Novenas and Prayers of Our Lady of the Rosary of Pompeii, translated by J.W. Levaux, Longo describes them as “lads of good will, sharp at work, ever cheerful and only too happy to please anyone.” A trauma-informed reader might recognize this as a response to the hardship these children experienced: raised in poverty, their parents taken away, their education and care tied to working with dangerous mechanized presses.

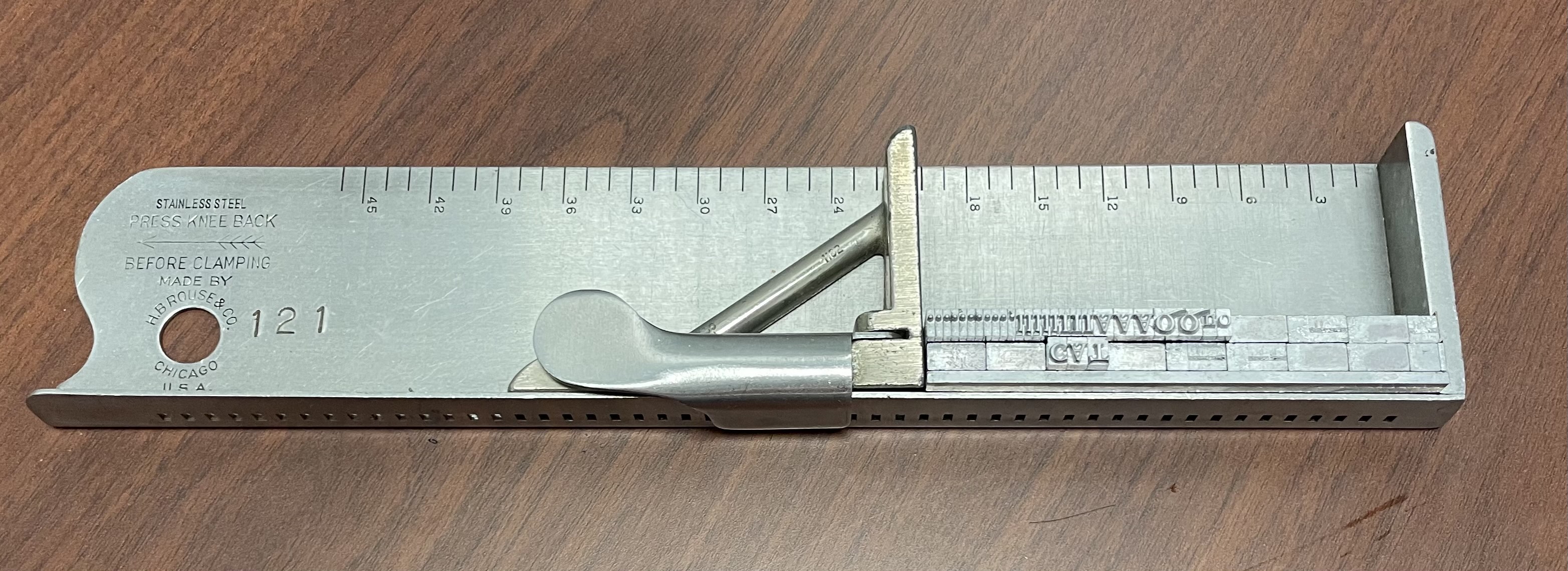

More than a century later, it’s humbling to hold a book or pamphlet printed by the school. They’re often small — the 1896 English History is just over 5 inches tall — which you might expect with personal devotional books and pamphlets, and they were produced by small hands. Those hands were indispensable to Longo’s vision and to the material survival of his work in the Marian Library now.

— Henry Handley is a collections librarian in the Marian Library, stewarding the circulating collections as well as pamphlets, periodicals and rare books.

(The first two photographs in this gallery are taken from Guida del santuario e della Nuova Pompei.)