University Libraries

Images of Kristallnacht

By Joan Milligan

This week marks the 84th anniversary of Kristallnacht, Nov. 9, 1938, when Nazis attacked Jewish people and property across Germany’s newly expanded domain. Its designation as Kristall (glass) Nacht (night) gives the impression that a few store windows were broken. It was much more than that. In addition to stores and houses, hundreds of synagogues were destroyed; 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps; and 91 were murdered. 1

Numbers such as these may be difficult to believe. Seeing pictures, however, knocks disbelief in the gut.

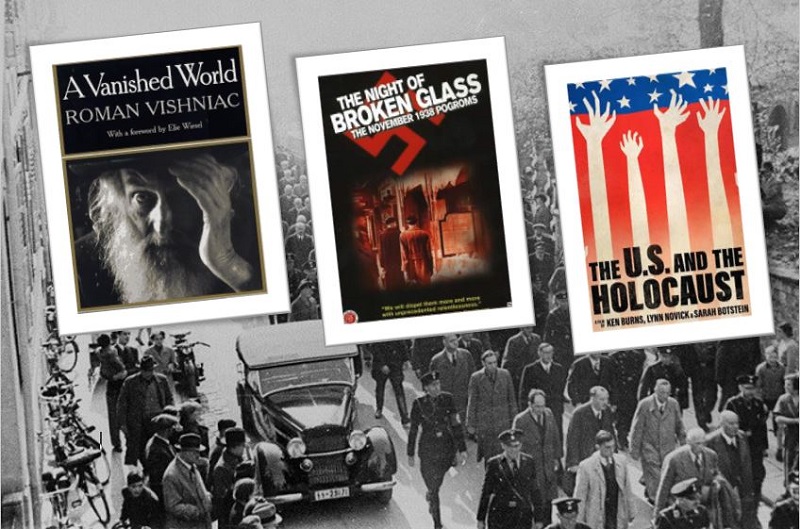

The Night of Broken Glass: The November 1938 Pogroms (2008), available through the Libraries’ subscription to Alexander Street streaming video, begins with amateur film footage of a Mardi Gras parade in Nuremberg earlier in the year. On one parade float, a caricature of a Jew hangs as if from a gallows. It is seemingly nothing out of the ordinary to the crowd enjoying the festivities. Film from Berlin in June shows workers tearing down the main synagogue, justifying its destruction by calling it a traffic hindrance. More film, photos and interviews document antisemitism as it grew. In November, a Jewish teenager whose parents had been forced from their home murdered a German official in anger. The German public was not told his motive, however, and this created the opportunity the Nazis had been looking for – an event to spark outrage against the Jewish population. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels wanted the destruction wreaked by Nazi party members to appear as spontaneous actions by the public.

Kristallnacht made the Jews’ need to get out of Nazi-occupied countries alarmingly obvious and urgent. As pointed out by Ken Burns’ latest documentary, The U.S. and the Holocaust (2022), the strict immigration laws in place in the United States and many other countries made this nearly impossible. Trapped in this way, many Jewish families were moved into ghettos, forced to leave behind their property — and their rights.

The sight of the Jewish ghettos is another jolt. One Russian-Jewish photographer, Roman Vishniac, made it his mission to show the world what life was like. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) realized the power of his pictures and hired him as part of a fundraising initiative. Sometimes as he walked the streets, Vishniac kept his camera hidden under his coat, knowing the Nazis would not want proof of their treatment of Jews to get out. Even so, he was caught several times, often suspected of spying, and put in jail.

He kept at it. Once he snuck into Zbaszyn, a holding camp for Jews being deported to concentration camps, then snuck out again with photos that were sent to the League of Nations. With help from family, he hid his negatives so that they would survive the war. Some did not, but you can see many in the books Polish Jews: A Pictorial Record (1973 reprint) and A Vanished World (1983), for which Holocaust survivor and author Elie Wiesel wrote the foreword.

Additional resources

Be a witness to what is happening in your world:

- Photography as Activism: Images for Social Change (2012) by Michelle Bogre; eBook

- Through the Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter (2022) by Lauren Walsh; eBook

- Regarding the Pain of Others (2003) by Susan Sontag; book

- 5 Broken Cameras: Non-Violent Resistance in the Middle East (2011) streaming video

- Amnesty International Report, free online

- Human Rights Watch World Report, free online

— Joan Milligan is a special collections cataloger and a member of the Libraries’ diversity and inclusion team.

1 Kristallnacht. United States Memorial Holocaust Museum.