University Libraries

'These Women'

By Camryn McNutt

Throughout my time as an intern in the University of Dayton Archives and Special Collections, I have had the opportunity to research the history of women at the University. Through the analysis of resources such as scrapbooks, magazines, yearbooks, photos and other publications, this blog post highlights the changing interests and activities of women at UD in the last 100 years. It also addresses the attitudes and gender dynamics that affected the participation of women in higher education during this time.

Female students first began to appear at the University of Dayton in the 1920s, during which time an average of five women were enrolled each year. They were admitted to classes in the evenings and on Saturdays, primarily through the School of Law. Despite being few in number, these women still found great success at the University. A prime example of this is Jessie Scott Hathcock ’30, the first African American woman to graduate from UD with a bachelor's degree.

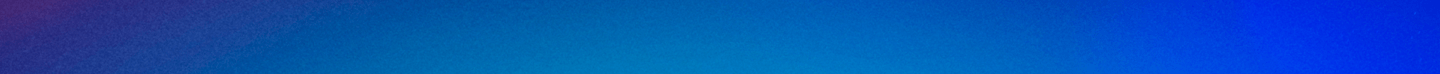

College of Women established

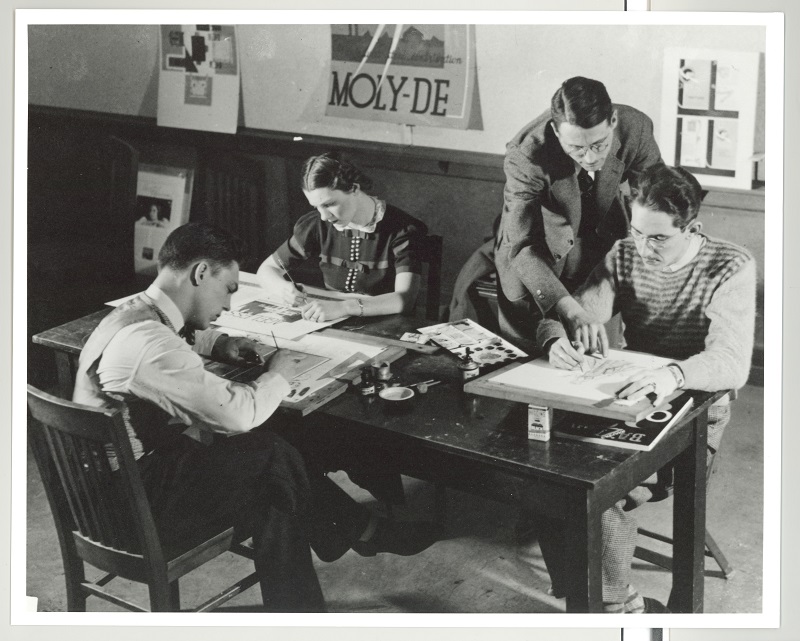

In the fall of 1935, the University of Dayton welcomed its first official class of women, or "coeds," as they were called, with the establishment of the College of Women. The original class consisted of 31 students, with Sister Marie St. Eleanor, S.N.D., appointed as the dean. The admission of women to the University was done on an experimental basis at the request of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, who were eager to build a Catholic college for women. Classes contained a strictly liberal arts curriculum and only took place in Albert Emanuel Hall in the evening in an effort to keep the women separate from the male students. The women students had their own lounge in Albert Emanuel Hall as well.

Traditional roles reinforced

For the first years of its existence, the College of Women found itself heavily influenced by traditional roles of women. Enrollment was contingent upon remaining single throughout their time at the University, and they were required to withdraw from the University if they wished to be married. The women were often in charge of setting up committees for various events, such as hosting dances or teas for the male students and faculty. In 1935, the first-year women entertained the first-year men and the members of the faculty at an open house. Instead of having the opportunity to attend themselves, they were put in charge of handling the decorations, refreshments, entertainment, invitations and responses. This is chronicled throughout publications and articles such as “College of Women at University of Dayton Plans Campus Tour and High School Tea Friday Afternoon”; “Trio Plans Mothers’ Tea at UD Wednesday”; “Plan Mothers Luncheon at Women's College”; “Women of University of Dayton Plan Open House Program to Introduce Campus Facilities”; “U.D. Sophomores Arrange For Card Party”; and “June Jamboree Committee has Conference.” While this illustrates the importance of such events during this time, it appears that their social events, rather than their academic achievements, received the most attention.

One article, “Co-Eds, Boys Express Views on Ideal Mate and Marriage,” published Nov. 9, 1936, in the Dayton Journal, featured three men and three women who attended the University. These students were asked to name the requisites for the person they would marry. The women all focused on personality and good character. The men, on the other hand, all called for a potential wife to conform to a specific beauty standard or possess “home girl” qualities:

- Tom Aspell is particularly active in social affairs at the university. His underlined requisite is that his wife be a “home girl” and definitely not a career woman or social climber.

He went on to specify that his future partner must be approximately 5-foot-4 and attractive, though not necessarily beautiful, and possess good cooking skills. The article continues:

- The captain of the football team, Charles Wagner, asks that his bride-to-be possess a pleasing personality without being a “popularity girl.” She also must be of the same religious affiliation as he. She must have a sense of loyalty and patience. She too, must be strictly a home girl and she must be and act feminine and not try to imitate the other sex in smoking or in any other manner. She must be able to think for herself without being obstinate.

The article is very telling of the social and gender norms during this time. Many of these women were making themselves less desirable by attending college and pursuing careers. Women seemed not to be viewed as men’s academic equals; the passages above indicate that some saw them more as prospects for marriage who offered nothing more than a social dimension to campus.

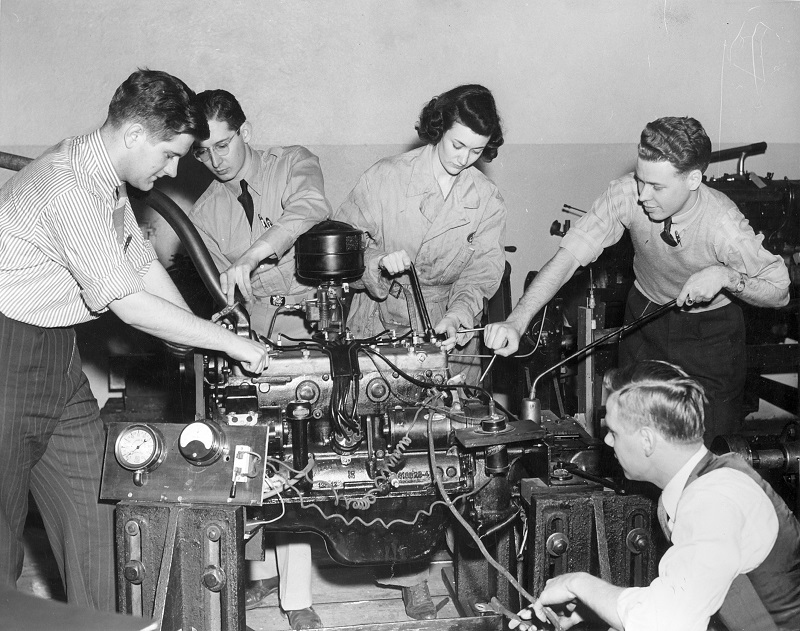

When the women were not participating in student life or attending classes, they would return to their off-campus housing. Though the University did not make housing available for female students, it still regulated the women’s housing options. In order to attend the University, a woman had to either commute from her Dayton-area residence or live with an approved guardian. Not until 1958, when Joan Chonacky was confined to the infirmary overnight, did a woman legally stay overnight on campus.

1936: All programs open to women

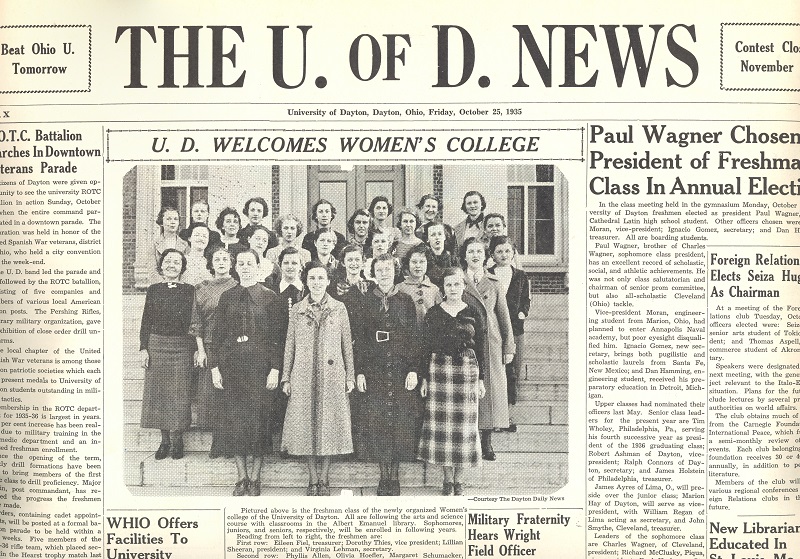

In the fall of 1936, the temporary nature of the agreement with the UD administration to hold classes for women on campus was expanded to allow the College of Women to offer studies in all departments. The University began to offer one-year scholarships to the top female graduates of local high schools. In August of 1937, the College of Women was discontinued, and female students were admitted on par with male students to all classes, although they were still required to sit on opposite sides of the classroom. The reception of all of this, for some, was one of disdain. The 1938 yearbook states:

- The men resented the fact that the days of slippers and no ties were past, and "These Women" were heard all too often on the campus. When, in September 1936, women actually invaded the sacred precincts of St. Mary and Chaminade Hall, many pessimistic predictions were made. ... Cool reception in classes and numerous glances warned us that our future was in a precarious state — we must either break down this wall of opposition or give up the cause.

This continued effort to segregate women from their male counterparts proved ineffective as coeds began to appear alongside men in class organizations and as cheerleaders at football games. They also received a new women’s lounge in Chaminade Hall and sponsored their first dance, called the Spring Swing. Within the first two years of the admission of women to campus, Isabelle Eck and two other women represented the coeds on the Student Council; Monda Hott became the first sponsor and honorary captain of the ROTC Pershing Rifles; and Lillian Sheeran was named the first homecoming queen. Women began to join the student newspaper, writing columns such as "Down in the Valley," "Credit Hours via the Midnight Oil," and "June Jingles," chronicling news and gossip from the night school. In September 1935, the Women’s Athletic Association was created and elected its first officers. Flyer athletics began offering tennis, volleyball, basketball, riding and hiking to women, and by 1938, five coeds had earned a "D" monogram for athletic achievement. Women were excelling in their studies, too, with 12 women earning recognition on the Dean’s List in the 1936-37 school year.

More firsts

University firsts continued well into the 1940s. The University was struck by the first death of a coed, Janet Breidenbach, killed in an automobile crash while returning from a school outing in Clifton, Ohio, on Dec. 15, 1940; UD awarded master’s degrees to three women for the first time on June 8, 1941; Susan J. Martin ’42 became the first woman to graduate from the School of Engineering (and did so with honors); and Pfc. Isabelle Moore ’40 was the first coed to lose her life in military service; she died in 1945. The presence of women on campus continued to grow in the early 1940s during World War II. The University recorded 314 female students by September 1945. In August of 1952, Pauline Louise Kelley became the first female valedictorian, and in 1962, the first women's residence hall, Marycrest, opened on campus. Flyer women were here to stay.

Studying the history of these remarkable women has allowed me to accrue a deeper understanding of the many struggles faced by women throughout the 20th century, especially while attending college. The analysis of archives and materials covering the history of women at the University of Dayton has given me a newfound appreciation for the unwavering perseverance and ambition of the women who have made an indelible mark on the University of Dayton campus throughout the past century.

More about women’s history at UD

Want to read more about women’s history at the University of Dayton? View the research guide and historical timeline.

— Camryn McNutt ’23 is a history major and spent the summer term as an intern in the University Archives.