University Libraries

Moses Moore: Entertainment and Sports

By Heidi Gauder

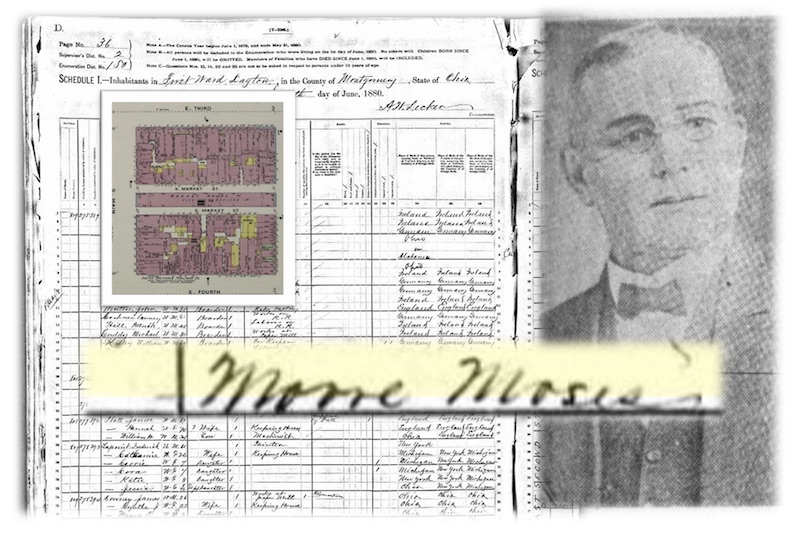

Part 4 of 6 in a documentary biography of Moses Moore, who became known as the wealthiest Black man in Dayton in the late 1800s. Librarian Heidi Gauder pieced together his history from census records, maps, newspaper clippings and local histories. You can read the other installments on the Roesch Library blog:

- Moses Moore: A Documentary Biography

- Moses Moore: Political Action

- Moses Moore: Business Grows

- Moses Moore: Building Portfolio

- Moses Moore: Community Needs

By the 1910 census, Dayton was a city of 116,577 people, of whom 4,842 were African American. As with the 1900 census, African Americans made up about 4% of the city’s population. Although this ratio shows comparable growth to the general city population, the number of African Americans reflected a more than threefold increase since 1880. This growth is attributed not to birth rates, but to migration to Ohio’s urban areas; historian David Gerber notes that African American death rates exceeded birth rates at this time in Dayton and other major Ohio cities.

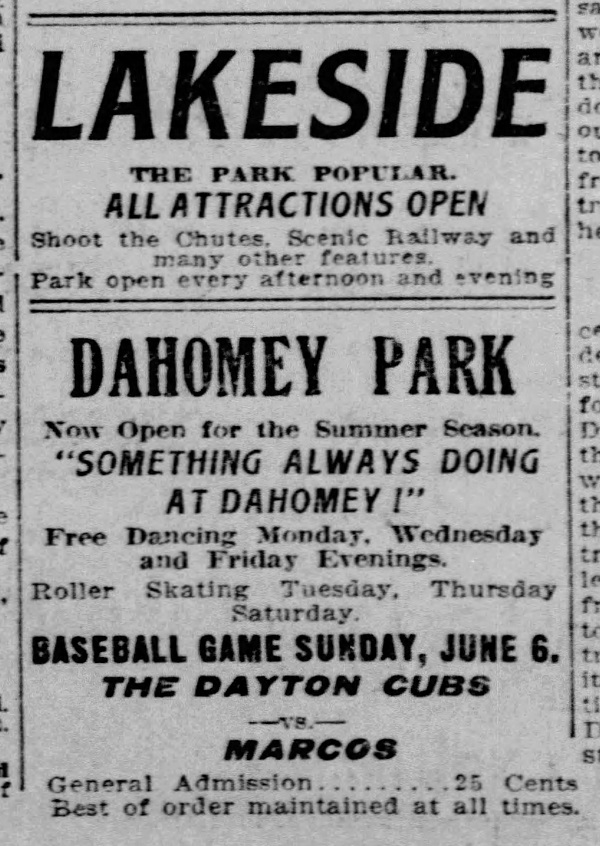

It was perhaps this growth in the African American population — in addition to discrimination — that spurred one of Moses Moore’s most ambitious enterprises: Dahomey Park, an amusement park for African Americans. As The Colored American magazine noted, “Mr. Moore has invested over $40,000 in his new venture and there is every reason to believe that it will prove to be a big success. The park is intended for the use of colored people and the patronage of others is not sought; but white people have been civilly treated and served when they visit the park.” Dayton already had another amusement park in the area, Lakeside Park, which was built in 1890 and located further west of Moore’s enterprise. Although it did not ban African Americans outright, they were not allowed in the dance pavilion and faced other discriminatory practices.

Dahomey Park opened in May 1909, and at the time, it was the largest African American-operated amusement park in the nation. It included a scenic railway, a roller skating rink, a merry-go-round, a bowling alley, a movie theater, an ice cream parlor, a restaurant, a photography gallery and a soda fountain. Dances in the park’s auditorium featured music performed by hired orchestras. Alcohol was strictly forbidden. The park’s name references not only the West African Kingdom of Dahomey — which existed from 1600 until its end as a French protectorate in 1904 — but also In Dahomey, the name of the first full-length musical written entirely by African Americans and performed at a major Broadway theater. Debuting in 1903, this musical featured lyrics written by the famous Dayton poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Marketing strategies draw masses

Moore advertised Dahomey Park in the Dayton newspapers as well as throughout the state and elsewhere. In Cleveland, for example, he promoted the park with an offer of 15% of the gross receipts from the park’s attractions in exchange for an organization’s visit to Dahomey Park. Newspaper stories about the park likewise appeared in Butte, Montana; Indianapolis; Nashville, Tennessee; and elsewhere. Moore’s strategy for inducing groups to visit appeared to have paid off, with multiple newspaper mentions of excursions by the United Brothers of Friendship, the “colored Elks,” the Republican Union of Cincinnati, Springfield Knights of Pythias and more. As Moore advertised, “Something always doing at Dahomey!”

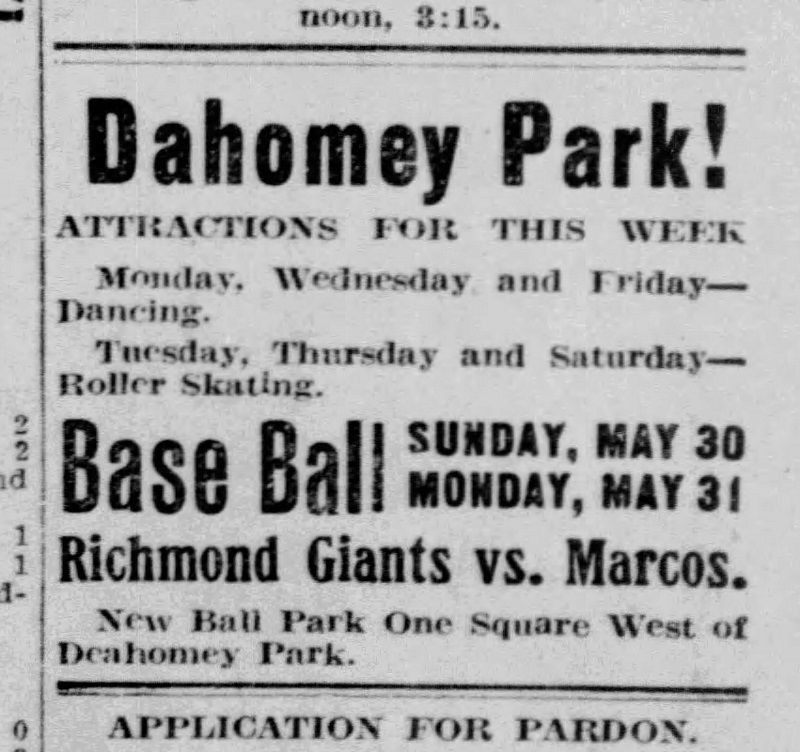

New attraction: Baseball

An added attraction to the park was the Marco Baseball Club, a semi-professional Black baseball team that played Both black and white teams during their first few years. The team’s home field, Marco Park, was right next to Dahomey Park with a stadium that included a grandstand and bleachers. Moore was involved in the baseball team’s inception, which began possibly as early as 1907, when Moore and others posted a notice of incorporation for the Progressive Athletic and Social Club in the Dayton Herald. Listed as the team president, Moore advertised both Dahomey Park and Marcos games at the same time in 1909. This was the beginning of a long history for the Marcos, which in 1920 became a founding team in the Negro National League. The team name has been attributed to the New Marco Hotel, 14 Market St., where the team’s manager, Harry Gardner, was the saloon proprietor. It is unclear whether Moore owned the saloon and hotel, given that he had sold property on the same street the year before.

Moore continued advertising the park and baseball games throughout 1910, but in September that year, the Dayton Journal reported that the Lakeview Improvement Association, the neighborhood around the park, demanded the park’s shutdown. The park’s assistant manager declared that the association needed to show “just cause why Dahomey park should be closed, and this they cannot do so long as the park is conforming to city authorities and is obeying the law.” The association clarified that it was insisting on a quiet observance of the Sabbath: “They believe the members of this race should be privileged to assemble for recreative purposes at a park, just the same as others.” In April 1911, Dayton’s mayor declined to order the park closed on Sunday.

Park closes; focus shifts

Before the end of the summer, however, the Dahomey amusement park appeared to be out of business. The 1911 summer advertising was far more restrained, listing only moving pictures and roller skating. Civic and social groups like the Oddfellows continued to use the park as an event space, but its role as an amusement park appeared to be over. An August 1911 Dayton Herald article noted that the “passing” of Dahomey Park left the “colored Y.M.C.A.” on Dunbar Avenue* as the “only exclusively colored club house in the city.” Neither the Dayton Daily News nor the Dayton Herald reported on the park closing beyond this remark; no advertising for the park appeared after 1911.

* Before Summit Street was renamed Paul Laurence Dunbar Street, another street — Baxter Street — was changed to Dunbar Avenue, thanks to a 1909 effort led by Edward Terrell Banks, a prominent West Dayton resident. Banks was also instrumental in organizing the first YMCA on Dayton's west side and worked to raise funds for a new YMCA at 907 W. Fifth St. (source: Edward Terrell Banks' obituary in the Dayton Herald, Nov. 15, 1939).

— Heidi Gauder is a professor in the University Libraries and coordinator of research and instruction. In locating records and information about Moses Moore and his family, she received assistance from Suzanne Dungan, Paris-Bourbon County (Kentucky) Public Library; Shawna Woodard, Special Collections, Dayton Metro Library; and Amy Czubak, Montgomery County (Ohio) Records Center and Archives. View the sources used in this series.