University Libraries

Overcoming Obstacles: Dayton Women Inventors

By Bridget Retzloff, Heidi Gauder

When you think about famous Dayton inventors, one often recalls the Wright brothers, Charles Kettering, Ermal Fraze, and perhaps Hans von Ohain. For a city its size, Dayton has a remarkable legacy of patents and inventions. You might also notice that all of these well-known inventors are men — white men at that.

The history of U.S. innovation, as told through patented inventions, is a lopsided story, as more patents have been awarded to people who are white, male and wealthier than other parts of the population — namely women, people of color and lower-income individuals. Part of the disparity stems from the data collection practices in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), as patent applications do not require demographic information. Even so, a 2020 report from the USPTO notes that patents with at least one woman inventor account for only 22% of patents issued.

People of color have long faced barriers to securing patents for their inventions; as intellectual property attorney Shontavia Johnson, associate vice president for entrepreneurship and innovation at Clemson University, notes, “Though the language itself was race-neutral, like many of the rights set forth in the Constitution, the patent system didn’t apply for Black Americans born into slavery.” Slaves were not considered citizens and were thus ineligible to hold property, including patents. Furthermore, costs associated with the patent application process likely proved to be a barrier to individuals with little savings. According to B. Zorina Khan, a researcher for the National Bureau of Economic Research and a professor of economics at Bowdoin College, these costs could amount to as much as $100 — roughly one-quarter of average annual non-farm wages in the late 19th century (nowadays, the patent application costs are roughly $10,000).

In spite of these hurdles, women and people of color have been inventing all along, and some have also been granted patents. In the course of our research, we found several Dayton women who secured patents for their inventions starting in the late 19th century. The innovations were often connected to domestic life and matters that were important to women, much like Khan found in her study of 19th-century women inventors.

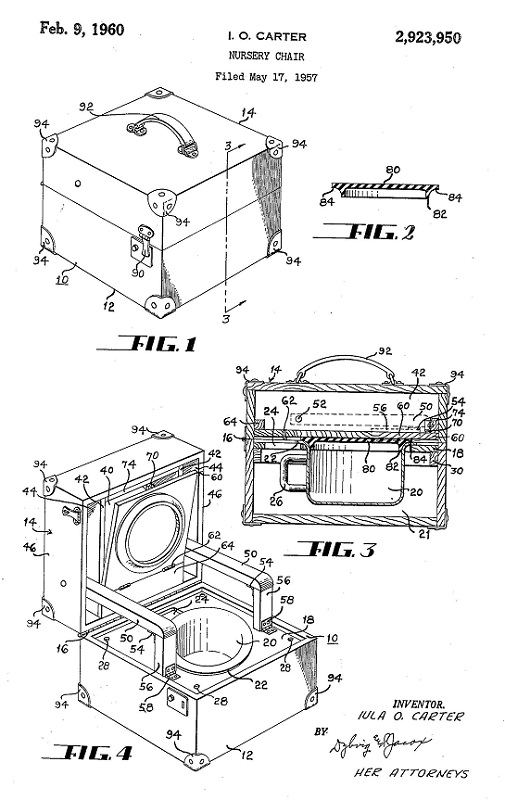

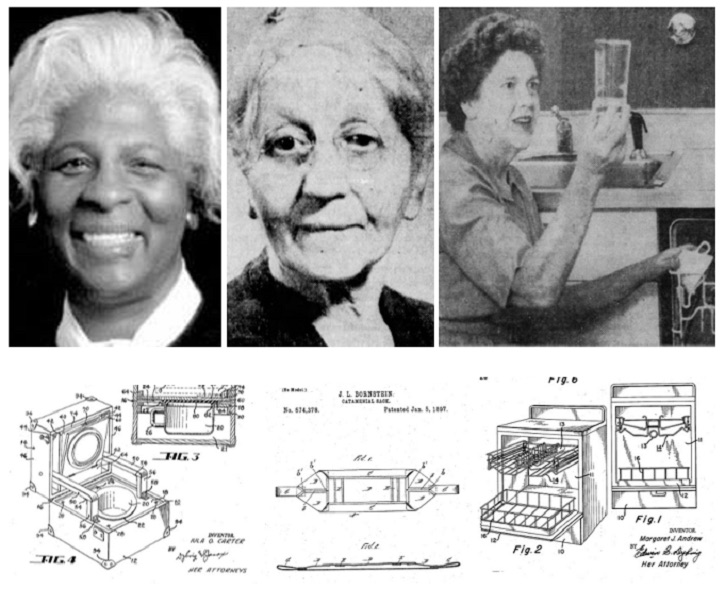

Iula O. Carter

As a Black woman in the 1950s, Iula Carter and her family had to travel to Middletown, Ohio, in order to swim in a public pool. On the road to Middletown and back to Dayton, at least one of the six children of Carter and her husband, William, would inevitably have to use the restroom. Seeking to make their trip easier, Carter invented a portable nursery chair in 1957 that folded into a suitcase when not in use. Carter’s husband urged her to patent her invention, and the patent was granted in 1960.

Carter hired a lawyer and had a mockup of the invention created. She even struck a deal with Rike-Kumler department store to sell the portable nursery chair. However, high production costs and prejudice prevented Carter from moving forward with production, and the patent expired in 1977.

Although her invention never took off, Carter inspired and encouraged other inventors, especially children, by educating them about Black inventors. She shared what she learned about patent, copyright and trademark law as the founder and director of the Dayton/Miami Valley Educational Affiliate of the National Intellectual Property Law Association. Carter was named one of the Dayton Daily News’ Ten Top Women, and her name has been added to the Dayton Hall of Fame. Carter saw a need and invented something to fill that need, then went on to encourage others to do the same.

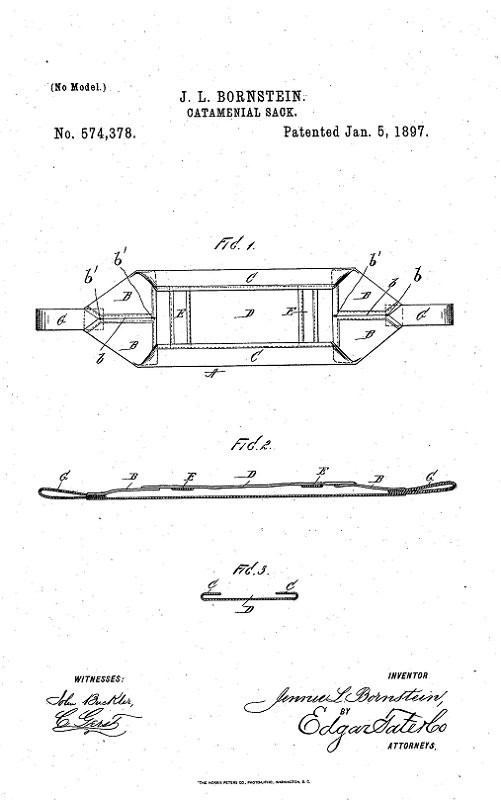

Jennie L. Bornstein

A reputable seamstress by the age of 15, Jennie Bornstein was working at Dayton’s Rike-Kumler department store in 1895 when, at the age of 41, she filed a patent application for a “catamenial sack,” a women's garment that would capture menstrual and sometimes bladder discharge in a leak-resistant pouch filled with removable cloths (though a 1937 profile of Bornstein in The Dayton Herald ostensibly found such a description unsuitable, choosing instead to identify it — both vaguely and redundantly — as "a practical, useful article for women to wear").

Bornstein continued to improve menstrual products around the turn of the century and was granted three more patents. She eventually left her job at Rike-Kumler and traveled the world selling her inventions, which later included a rubberized apron and diaper method that was still in use in 1937. Menstruation’s taboo status during Bornstein’s life may have prevented her from receiving much recognition, but women are surely benefiting from her ingenuity, which paved the way toward safer and more sanitary menstruation products.

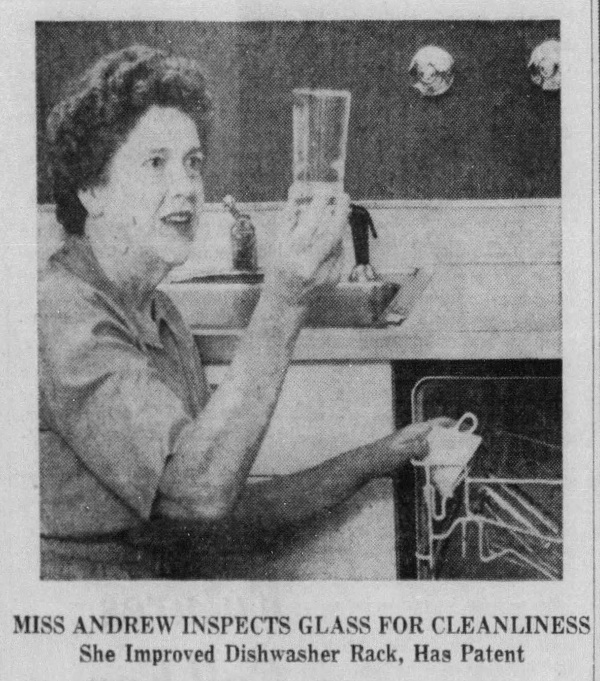

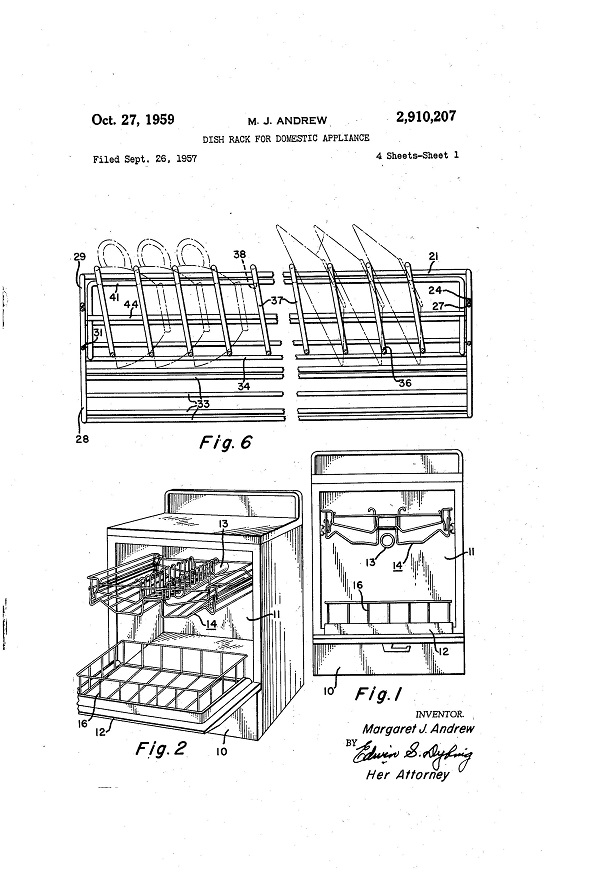

Margaret J. Andrew

Margaret Andrew is another Dayton woman who saw a need for improvement and innovated products to meet that need. Andrew was an experimental engineer for the Frigidaire division of General Motors after spending 17 years in customer research. Going door to door and finding out how people used Frigidaire’s products gave Andrew a different perspective from those of the male engineers with whom she worked.

A 1964 Dayton Daily News profile of Andrew tells this story of her work at Frigidaire: “It didn’t take more than a couple days for Margaret to decide that the top rack just didn’t hold enough glasses. She not only told the engineer what was wrong with it — she also got some wire and shaped it into the kind of rack she wanted—one that would hold 26 glasses instead of 12. She improved the same dishwasher rack twice and had two different patents issued in her name.” Andrew also patented improvements to the washing machine, including improved agitation control.

In 1983, Andrew published Home Food Care, which was used as a textbook on home food handling and preparation. She was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame in 1986, an honor recognizing Ohio women who have made “significant contributions to the social, economic, political and cultural growth” of the state and the nation.

Although they are not as well-known as the Wright brothers, these women share similar traits with them: ingenuity, creativity and a drive to lay claim to their novel ideas. In securing patents for their inventions, these women helped propel innovation in spite of structural racism, gender discrimination, gaps in educational access, and economic barriers. Hopefully, the future will see more gender, race, and income diversity in invention and patents.

— Bridget Retzloff is a lecturer in the University Libraries. Heidi Gauder is a professor in the University Libraries and coordinator of research and instruction.

SOURCES

- “2 Dayton women to join hall of fame.” Dayton Daily News. August 22, 1986.

- Dunlap, Jean. “Engineer’s Motto: Trial and Error Success Formula.” Dayton Daily News, September 8, 1964, 8.

- Fechner, Holly, and Matthew S. Shapanka. "Closing diversity gaps in innovation: Gender, race, and income disparities in patenting and commercialization of inventions." Technology & Innovation 19, no. 4 (2018): 727-734.

- Johnson, Shontavia. “America’s always had black inventors – even when the patent system explicitly excluded them.” The Conversation, February 14, 2017.

- Khan, B. Zorina. “‘Not for ornament’: Patenting activity by nineteenth-century women inventors.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 31, no. 2 (2000): 159-195.

- National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center. “Black History Month profile: Iula O. Carter: Inventor, teacher and writer (b. 1926).” Dayton Daily News, February 26, 2006.

- “Pioneer Resident Lives By Herself and Likes It.” The Dayton Herald. February 23, 1937, 7.

- Robinson, Amelia. “Inventor continues to share expertise.” Dayton Daily News, January 28, 2002.

- Toole, Andrew A., Michelle J. Saksena, Charles A. W. Degrazia, Katherine P. Black, Francesco Lissoni, Ernest Miguelez, & Gianluca Tarasconi. "Progress and Potential: 2020 update on U.S. women inventor-patentees." Office of the Chief Economist, United States Patent and Trademark Office, 2020.