University Libraries

‘The Considerable Number of Students’: A Response to W.E.B. Du Bois

By Heidi Gauder and Caroline Waldron

Only by critically and openly examining our past can we make progress toward racial justice. When Caroline Waldron, associate professor of history, discovered this letter — a response from the University of Dayton to a query from W.E.B. Du Bois about Black enrollment at UD in 1930 — it was an opportunity to seek answers and reflect on their meaning, no matter how uncomfortable.

This blog supports the priorities from An Open Letter to the University of Dayton Community from Members of the President’s Council Regarding Steps Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist University and the University Libraries' Commitment to Anti-Racism.

Please see this video about the University's response to the letter.

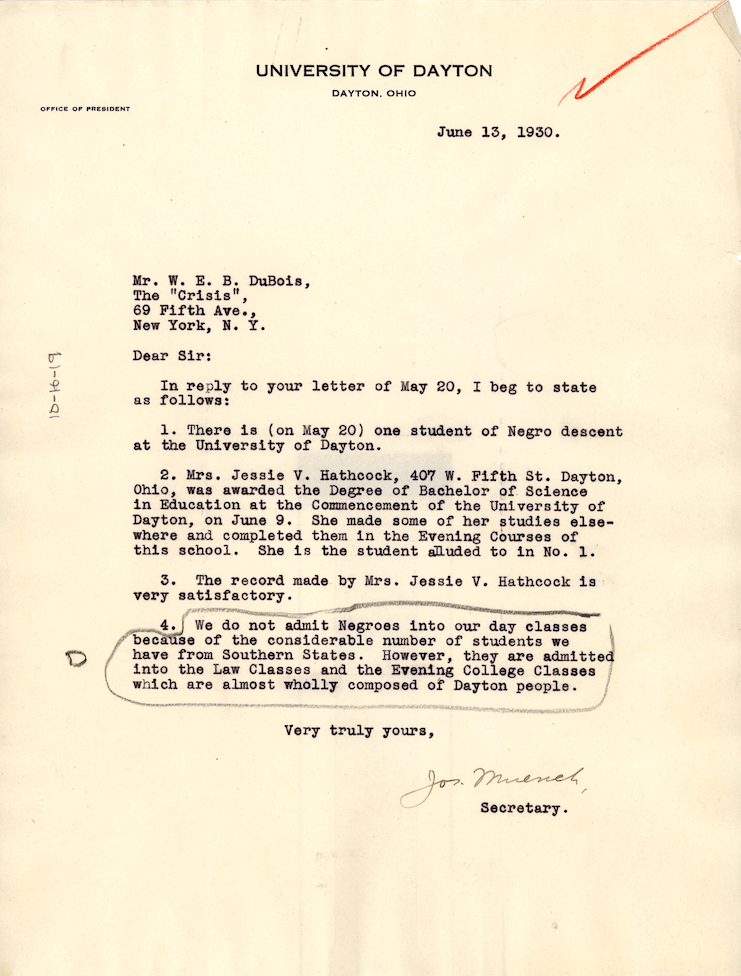

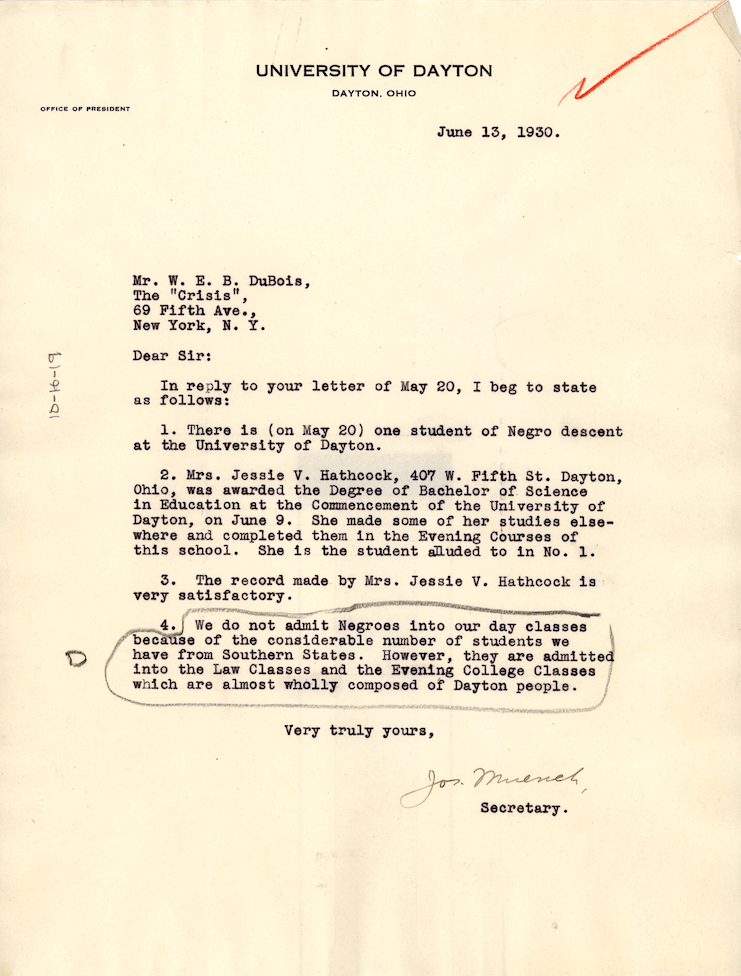

The letter is brief, dated June 13, 1930, and clearly a reply to an inquiry. It is a total of four numbered paragraphs. What makes it interesting is the letter’s recipient and its explanation about the number of African American students at the University of Dayton in 1930. In replying to W.E.B. Du Bois, editor of The Crisis, Brother Joseph Muench, S.M., notes that Jessie V. Hathcock is the only African American student at the University of Dayton, that she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in education less than a week prior, and that her academic record was “very satisfactory.” More telling, however, is the last paragraph, where Muench explains that the University does not admit African American students into the day classes, but they are enrolled in the law and evening college classes.

Why did The Crisis want to know about African American students at the University of Dayton? As part of its annual education issue, The Crisis collected information about African American student enrollment and achievements at various post-secondary institutions. The August 1930 issue reported on the survey results, including “The Attitude of White Colleges Toward Negro Students,” in which Du Bois observed, “Most of the institutions reporting deny having any restrictions on Negro students although it is known that in some cases they do.” He described some institutions as “noncommittal,” in that few African American students apply, and for others that do admit African American students, they are not allowed to live on campus. Catholic schools, he noted, are noncommittal, although the University of Dayton was less circumspect than other schools in stating the reason as the “considerable number of students from the Southern States.”

How “considerable” a number of students from the Southern States would make it incompatible to admit African American students to the day classes? According to the Register of Students, 1925-1940, found in the University Archives, the number is not much. In the academic year 1929-30, the total number of high school and college students enrolled was 553, of which 22 were from the South: two each from West Virginia and Tennessee; one from Virginia; three from Missouri; and 14 from Kentucky. In the 1930-31 academic year, the ratio was roughly the same: Of the 579 students enrolled in the high school and University, 24 were from the South (Kentucky, 18; West Virginia, Virginia and Tennessee, one each; Missouri, three). The prior 1928-29 academic year shows the same pattern: 31 of the 614 students were from Southern states. For the University of Dayton in 1930, the year that Hathcock graduated, it took just 4% of the student population to exclude another population altogether. It is unclear — and there is no known documentation to confirm — whether it was the Southern students themselves who raised the issue or if it was the administration that effectively segregated African American students.

Although a “considerable number” prevented Hathcock from attending the University’s daytime classes, she was a formidable person in her own right. In a Jan. 20, 1967, Dayton Daily News article, Hathcock noted that the first time she applied to the University of Dayton, she was rejected on the basis of race, though her later efforts proved successful. The letter from Muench would not be the only time that Du Bois encountered Hathcock’s name; correspondence between Hathcock and Du Bois spanned from 1925 to 1951. She was in charge of a committee that brought Du Bois to Dayton in February 1940 to speak on “Democracy and the Darker Races.” She corresponded with Du Bois directly, sending him a telegram on Feb. 23, 1948, for his 80th birthday, congratulating him on “the richness of your years and the fullness of your life and your friendship.” Hathcock taught in the Dayton Public Schools for many years, retiring in 1964, but continued to serve the city through her work on the Dayton Council on World Affairs, the City Beautiful Council, the Wegerzyn Garden Board, the American Association of University Women and the Dayton and Miami Valley Committee for UNICEF. In 1978, the University of Dayton awarded her an honorary doctorate, and in 2018, she was recognized again during Women’s History Month.

The University’s answer to Du Bois in 1930 is but one of many indicators that racial segregation and employment discrimination were by no means Southern phenomena in the 20th century; they were alive and well in Dayton and across the Midwest. Want ads in the Dayton Daily News and the Dayton Herald contained explicit race preferences; real estate ads specified racial exclusion; and swimming pools and schools were segregated, along with restaurants, theaters and hotels. Decades later, segregation remains; in 2016, the Brookings Institution found that the Dayton metropolitan area was the 14th-most segregated large metropolitan area in the nation.

At the time of Du Bois’ inquiry, though UD had no specific policy about race in admission, the subtext until the 1940s was clear: With very limited exception, African American students admitted to the University would attend evening classes.

Today, as we contend with making the campus a more diverse, equitable and inclusive place for all, we also acknowledge the history of segregation that surrounds us.

— Heidi Gauder is a professor in the University Libraries and coordinator of research and instruction. Caroline Waldron is an associate professor of history. Kristina Schulz, University archivist and coordinator of special collections, also contributed to this story.

Postscripts

W.E.B. Du Bois is a noted civil rights activist in 20th-century American history. The University of Massachusetts Amherst Special Collections describes him thusly: “Scholar, writer, editor of The Crisis and other journals, co-founder of the Niagara Movement, the NAACP, and the Pan African Congress, international spokesperson for peace and for the rights of oppressed minorities, W.E.B. Du Bois was a son of Massachusetts who articulated the strivings of African Americans and developed a trenchant analysis of the problem of the color line in the 20th century.”

The Crisis magazine describes itself on its website as a “quarterly journal of politics, culture, civil rights and history that seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues facing African-Americans and other communities of color.” It was founded in 1910 and is the official magazine of the NAACP.

The University of Dayton began as St. Mary’s School for Boys in 1850; it was incorporated as a college in 1878 and continued to educate at the elementary, preparatory and post-secondary levels until the late 1930s, at which point it offered only collegiate-level programs.

Sources

- “Dr. DuBois to Give Talks Here.” Dayton Daily News, February 16, 1940, p. 30.

- Hathcock, Jessie. Telegram from Jessie Hathcock to W.E.B. Du Bois, February 23, 1948. W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b119-i019

- Morrow, Pat. “Retired Teacher Refurbishes House and People.” Dayton Daily News, January 20, 1967, p. 21.

- Schulz, Kristina. “Jessie Hathcock.” Women of UD exhibit, 2018. University of Dayton Women’s Center. https://udayton.edu/womenscenter/education/whm/whm18/hathcock.php

- Sweigart, Josh. “50 Years Ago, West Dayton Boiled Over.” Dayton Daily News, September 4, 2016, p. 1.

- “The Year in Negro Education. 1930.” The Crisis. August, 1930, p. 262-268. https://books.google.com/books?id=zVcEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA257&pg=PA262#v=onepage&q&f=false

- University of Dayton. Letter from the University of Dayton to W.E.B. Du Bois, June 13, 1930. W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b184-i578

- University of Dayton. Register of Students, 1925-1940. University Archives.

Letter, 1930

University of Dayton. Letter from the University of Dayton to W.E.B. Du Bois, June 13, 1930. W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b184-i578

Letter, 1930