University Libraries

Documents, Records Reveal Stately Mansion's Unstately Origins

By Heidi Gauder

I could see the top of the house’s stately French mansard roof and ornate third-floor windows nearly every day on my way home from work this past winter, before the pandemic changed our current routines. The bare trees allowed for glimpses that could not be seen in the spring and summer, and now I could more easily view the yellow, green, and red house off in the distance, sitting on one of Dayton’s eastern hills. Just as winter reveals the house every year, the history of its first occupant was as revealing, not only for his life in Dayton, but more importantly for how he acquired his wealth through slave labor and the reverberating effects of that part of our nation’s history.

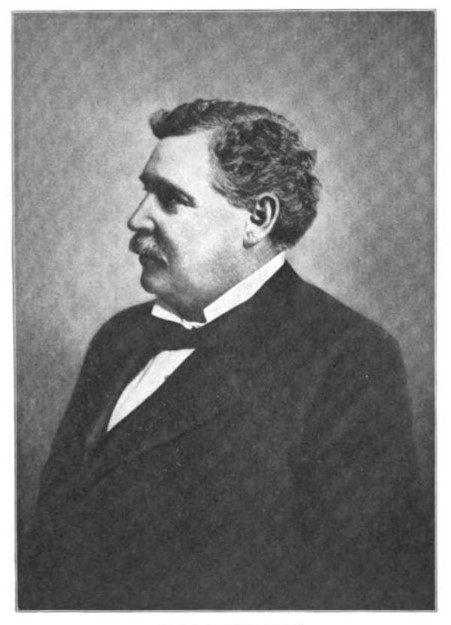

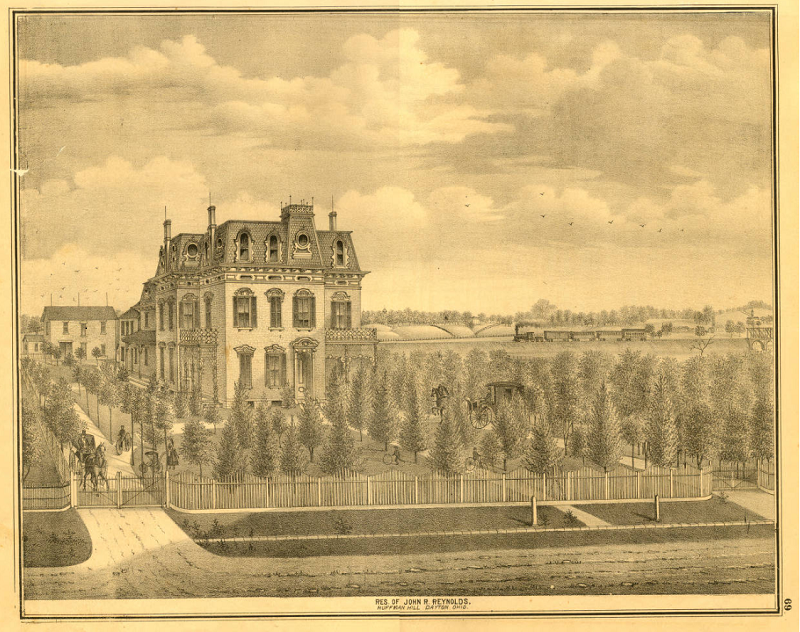

The house, at 24 Klee Ave., is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. According to the Montgomery County Auditor’s website, it was built in 1865 in the Second Empire style and includes nearly 6,000 square feet in living area, an impressive size even by today’s standards. A.W. Drury’s History of the City of Dayton and Montgomery County, Ohio (1909) identified the homeowner as John Russell Reynolds, noting that he moved his family into this house in 1867 and lived there almost the rest of his life.

Cultivating wealth: Dry goods, shipping, cotton, coal ... and slavery

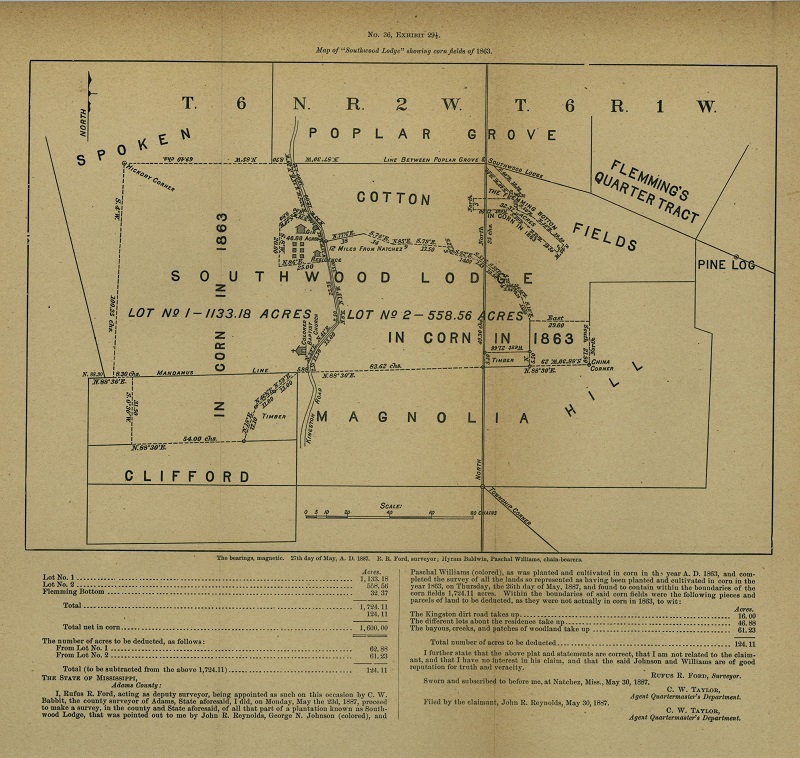

Reynolds was born in 1831 Pennsylvania, but left in 1851 to live with a widower uncle, James Reynolds, in Natchez, Mississippi. According to the Biographical Cyclopaedia of Ohio, Reynolds ran several enterprises once he settled there: a dry-goods business under the name Boyd & Reynolds; a steamboat business known as Smyth & Reynolds; and finally an ice and coal trade known as Reynolds, Green & Co. By 1859, he had accrued enough wealth to purchase half the interest in his uncle’s farm, known as the Southwood Lodge plantation. What this entry and Drury’s both fail to mention is the size and scale of this slave plantation. In 1840, James Reynolds owned 166 slaves — 89 men and 77 women — on a nearly 3,000-acre plantation. By 1860, he and his nephew owned 216 slaves; that year, his real estate was valued at $20,000, and his personal estate — his property, including the 216 men, women and children — was valued at $200,000 (this figure has a relative worth of approximately $6 million today, according to various internet inflation calculators). When his uncle died in 1864 without any heirs, John R. Reynolds became the sole owner of the estate.

Historian William Scarborough observed that the Natchez district included three-fourths (55 of 71) of Mississippi’s largest slaveholders (those with 250 or more slaves), a social class described as Natchez nabobs. Although neither James nor John Reynolds was in this category, they shared important characteristics with this group. Interestingly, the majority of the Natchez slaveholders were Unionists before the war and remained as such during the conflict. This aspect was not limited to Natchez: many Southern Unionists, including the future President Andrew Johnson, were slaveholders. Scarborough notes that half of this group were not even Southerners, much less Mississippians, by birth. Like the Reynolds uncle and nephew, many came from the Northeast, like Pennsylvania. These families maintained ties to that region, sending children to the Northeast for their education, conducting business through Northeast brokers and taking extended family trips to the Northeast. And, like other Natchez planters, John R. Reynolds probably had a strong economic self-interest in mind during the war and might have tried to sell his cotton during the war, despite a Confederate embargo on the shipment of cotton abroad; Drury’s biography notes that he lost an estimated $250,000 worth of cotton when it was burned at New Orleans through the orders of Gen. Benjamin Butler.

Venture moves north

Despite his financial losses during the war, John R. Reynolds left Mississippi in 1864 a wealthy man. He spent the second half of 1864 on a European tour, returned to the States and, after a brief courtship, married Jennie McCoy of Springfield, Ohio, in April, 1865. He went back to Southwood Lodge after the war, due to, per the Biographical Cyclopaedia of Ohio, “the earnest solicitation of those surviving of his former slaves,” but stayed for only a year, finding the venture “unprofitable.” Based on newspaper accounts in 1866, he was probably also drawn to Natchez in order to settle his uncle’s estate. By 1870, John and Jennie were settled in the big Dayton house, living in “suburban” Mad River Township.

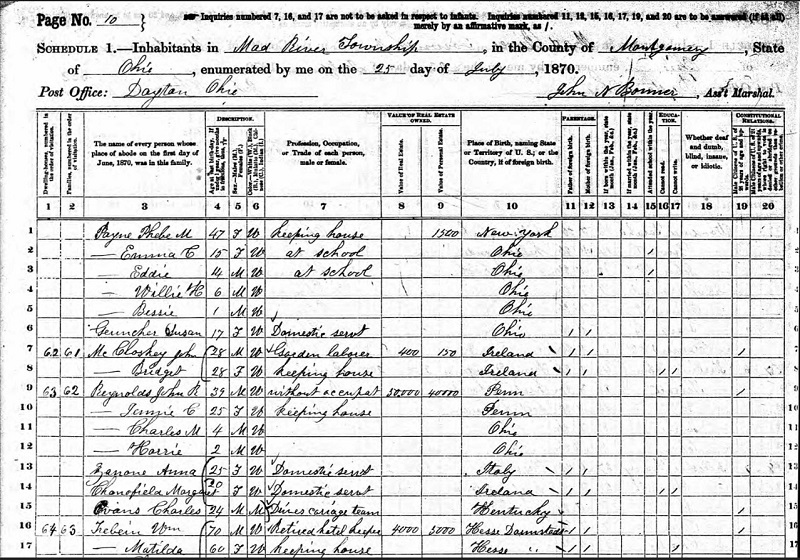

The 1875 Montgomery County atlas includes an engraving of the Reynolds house situated on Huffman Hill. Its front yard extends to what is now Huffman Avenue; it also had a circular driveway in the front and a carriage house in the back. The house itself is large and ornate. The 1870 Census offers additional insight into the house’s occupants. The Reynolds family had grown by two children, and along with the family, other occupants included two domestic servants and a carriage driver. John Reynolds is listed as “without occupation,” yet has real estate holdings valued at $50,000 and a personal estate of $40,000. Neighbors on Huffman Hill included Eugene Barney, “railroad car builder”; Edwin Payne, “flax manufacturer”; and William J. Huffman, “banker & real estate dealer.”

Collecting on Union debt

Despite his life in Dayton, the Southwood Lodge plantation remained on his mind, even if he no longer owned it (a Sheriff’s sale was held in January 1869). After the war, Reynolds submitted a claim to the U.S. government for reimbursement of quartermaster and commissary stores and supplies taken by the Union Army during the war. His claim was for nearly $72,000, or roughly $1 million today. Reynolds began pursuing claims as early as 1868, but the House Committee on War Claims did not commence an investigation until 1887. By then, Reynolds had accrued a large set of testimonials as to his Union loyalty and the extent of supplies taken by the Union Army. Former slaves testified to Reynolds’ Union loyalty:

- Albert Russell, about fifty years old, swears that he lived on the “Southwood Lodge plantation” from 1853 till the spring of 1864; that the rebels were after claimant and wanted to kill him, because they said he was a Yankee; that claimant went to Natchez and remained there after the Yankee army came. The rebels abused and robbed claimant’s uncle, Master James, and threatened to kill him, calling him an old Yankee and a damned old Union man. He also had to go to town for safety.

Reynolds was one of few to secure reimbursement, as only 32% of those who appealed to the Southern Claims Commission were approved for payment.

News of his claims were reported in Natchez as well as Dayton, Ohio. In Dayton, while his claims were being considered by the federal government, a rumor circulated that he was also a Confederate during the war. When a reporter from the Dayton Herald asked him about the rumor, Reynolds asserted,

- But I want to say now, and here, for the last time, that I was not in the rebel service; that I was not on Beauregard’s or any other rebel general’s staff; that I was a loyal citizen of the United States, and having large interests in the South on the breaking out of hostilities, I remained in the South for a while after the breaking out of hostilities, to try to secure my property — or, at least, a part of it. I was always loyal to the United States, was always a citizen of the Union, and recognized the stars and stripes, and no one can say to the contrary.

Ashleigh Lawrence-Sanders, assistant professor of African American history at UD, points out that Reynolds’ statement of loyalty to the Union shows the complexity of the war and slavery: “The South wanted to preserve and expand slavery; the North wanted to keep the nation together. The North did not become emancipationist until it was pushed in that direction by Black people’s own agency. The existence of Southern Unionists like Reynolds who can make statements about being loyal to the U.S. as a former slave owner is a good example of this.”

Next generation reaps wealth's spoils

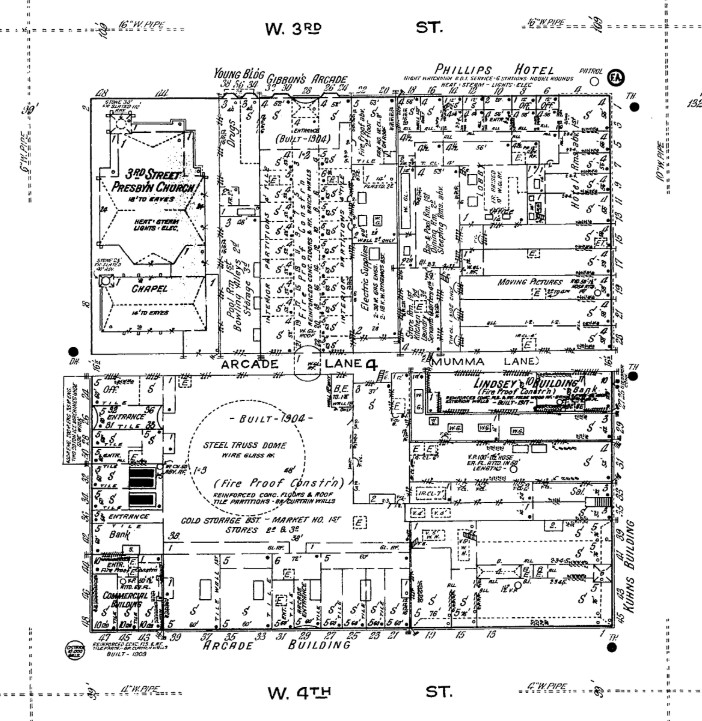

John and Jennie Reynolds raised four children at the house on Huffman Hill, socializing with the city elite. One of their sons married the daughter of his neighbor, Eugene Barney. Their only daughter, Gertrude, married and divorced Frank Mills Andrews, the architect of the Dayton Arcade on West Third Street downtown and the Conover Building, at the southeast corner of Third and Main streets. By 1889, John and Jennie Reynolds relocated to downtown Dayton, where they lived at 40 E. First St. His death in December 1893 merited a mention in the Dayton Herald’s front-page obituary section, colorfully labeled “Death’s Harvest,” under the headline “John R. Reynolds Passes Peacefully Away to His Long, Last Sleep. His Demise Was Sudden, but Tranquil.”

During his time in Dayton, John Reynolds did not return to his entrepreneurial roots, choosing instead to make “financial investment(s) in business enterprises.” He was a director of the Merchants National Bank and of the Fireman’s Insurance Co. and invested in stock and property as well. Although he shared the same last name, John Reynolds was not related to Lucius Reynolds, the co-founder of Reynolds & Reynolds, a business forms manufacturing firm. By the time the executors of his estate were appointed in 1895, his estate was estimated to be $492,000. That figure would increase in value, in part because he owned some of the land on which the Phillips Hotel was built. The prominent hotel, at the southwest corner of Main and Third streets, sat next to the Arcade. When the estate was finally settled in 1910, an article in The Cincinnati Enquirer paper noted, “After litigation extending over a quarter of a century, the famous John R. Reynolds estate, involving nearly $1,000,000, has been settled.

Dazzle dims with disrepair, decay

Today, the house sits among smaller family houses built in the early 20th century. It has lost some of the grandeur that was obvious in the 1875 engraving and is somewhat dilapidated. The large front lawn is gone, as is the circular driveway, replaced by another house. The carriage house is likewise gone. Renovating the house is challenging: it is not in a historic district, and although there are other fine houses in the area, like the Gilbert house (1012 Huffman Ave.), the Gottschall house (20 E. Livingston Ave.), the Burkhardt mansion (535 S. Wright Ave.), the Gummer house (1428 Huffman Ave.) and others, there is little possibility of securing historic tax credits to fund the necessary improvements.

The wealth John Reynolds generated from slave labor is unmistakable. He was able to transfer this wealth to Dayton and invest and increase that income, showing the staggering benefits that the owners reaped from slavery. Reynolds “retired” from work by age 39, raised his family in comfort and socialized with other elite families. It should serve as notice that the impact of slavery was not confined to the South. That a number of Northern families ran plantations using enslaved people, then returned North with the wealth to raise families and engage in business shows us yet another component of the systemic inequality we continue to wrestle with today.

— Heidi Gauder is a professor in the University Libraries and coordinator of research and instruction.

Sources

Brennan, J.F., A Biographical Cyclopaedia and Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Men, With an Historical Sketch of the State of Ohio. Cincinnati: J.C. Yorston & Co., 1879. Available at: Google Books.

Drury, A.W., History of the City of Dayton and Montgomery County, Ohio. S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1909. Available at: Google Books

Everts, L.H., Combination Atlas Map of Montgomery County, Ohio. Philadelphia: Hunter Press, 1875. Available at: Dayton Remembers: Preserving the History of the Miami Valley. http://content.daytonmetrolibrary.org/digital/collection/maps/id/198/rec/1

Phillips Hotel & Arcade building, Sanborn Map series. Dayton, Montgomery County, Ohio. vol 1, 1918, sheet label 34.

Reynolds, James M. 1840 United States Federal Census. Adams, Mississippi, roll: 213, p. 36. Family History Library Film: 0014840. Available at: HeritageQuest. Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Reynolds, James M. 1860 United States Federal Census. Adams, Mississippi, p. 136. Family History Library Film: 803577. Available at: HeritageQuest. Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009.

Reynolds, John R. 1870 United States Federal Census. Mad River, Montgomery, Ohio, roll: M593_1248, page: 622B; Family History Library Film: 552747. Available at: HeritageQuest. Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009.

Scarborough, William K. "Not Quite Southern-The Precarious Allegiance of the Natchez Nabobs In the Sectional Crisis." Prologue-Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 36, no. 4 (2004): 20.

U.S. Senate, 50th Congress, 1st Session. Letter from the Secretary of War, transmitting a report, in response to Senate resolution of March 2, 1887, relative to the claims of John R. Reynolds (S. Exdoc 30). Washington, Government Printing Office, 1887. (Serial Set 2504). Available at: Proquest Congressional, https://congressional.proquest.com/congressional/docview/t47.d48.2504_s.exdoc.30?accountid=14607

U.S. Senate, 50th Congress, 1st Session. Map of “Southwood Lodge” showing corn fields of 1863 (S. Exdoc 30). Washington, Government Printing Office, 1887. (Serial Set 2504). Available at: Proquest Congressional. https://congressional.proquest.com/congressional/docview/t45.d46.2504_s.exdoc.30_map_1?accountid=14607

Newspaper sources

Advertisement for Smyth & Reynolds, Mississippi Free Trader & Natchez Gazette, Apr. 29, 1856, p. 2.

A Big Claim Against Uncle Sam, Weekly Democrat, Aug. 1, 1888, p. 3.

Cincinnati Enquirer, Aug. 13, 1910, p. 13.

Death’s Harvest. Dayton Herald, Dec. 30, 1893, p. 1.

Legal notice, Dayton Herald, May 24, 1895, p. 3.

Legal notice, Natchez Daily Courier, Sept. 19, 1866, p. 3.

Mr. Reynolds interviewed by a Herald reporter, Dayton Herald, Dec. 11, 1888, p. 2.