Blogs

Building peace, creating dialogue

By Brenna R. Seifried

“There was a sense, for many of us in the Peace Studies Institute, that PSI needed to be an agent for effective, social change and not merely a course of study in which students tracked their GPA. Personally, PSI was a serious, heady, challenging, life-changing experience for me.”

-Wayne Wlodarski ‘75

What does it take to compel warring nations to lay down their weapons? What conditions have to be right for dialogue to happen between adversaries? How can we create space for people to build understanding? What are the ingredients for peace?

In the case of the Peace Studies Institute (PSI) at the University of Dayton, the ingredients were a few inspired UD students who were passionate about peace, an Associate Provost committed to innovative teaching and learning, and a Marianist brother called to the work of building peace.

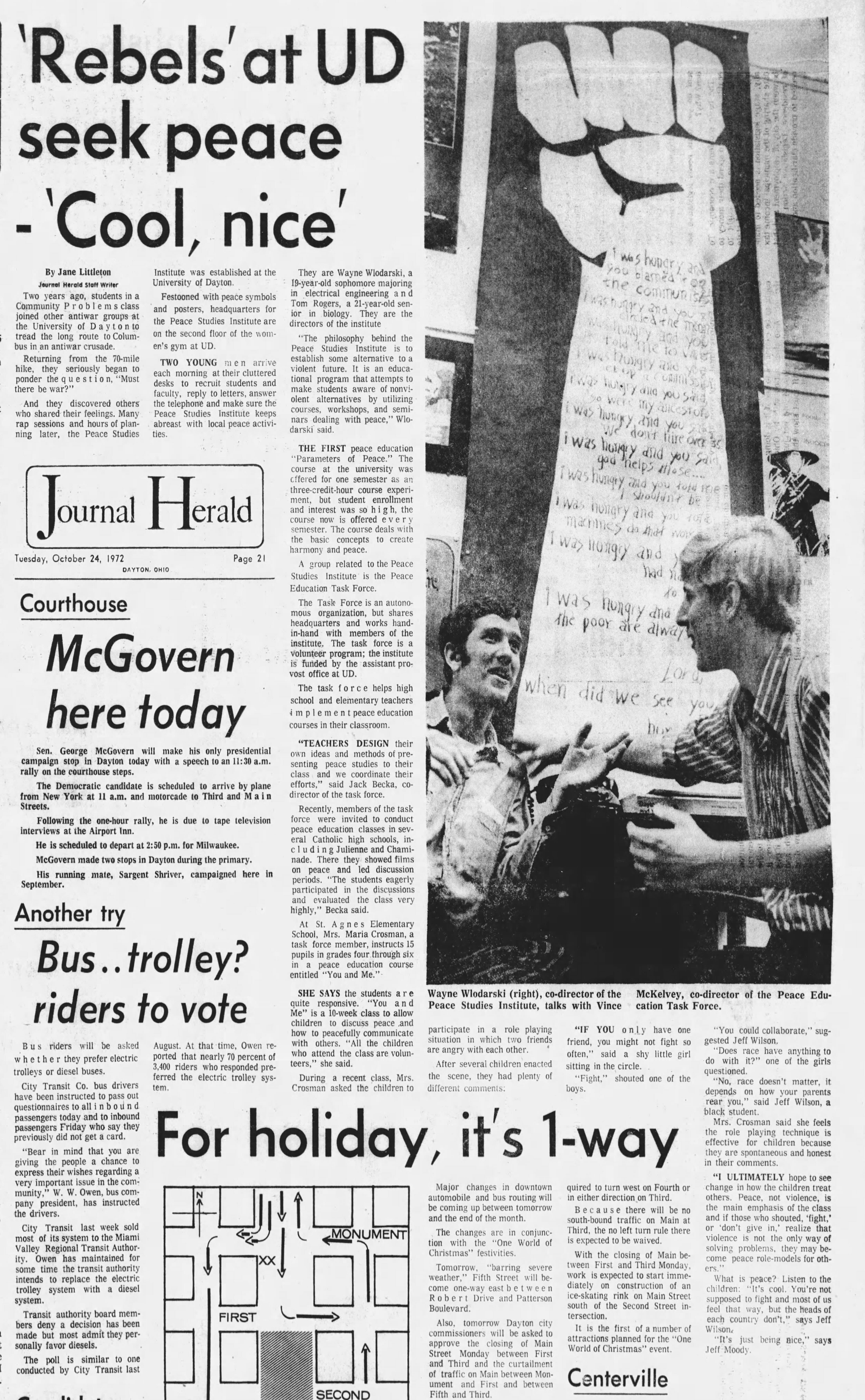

It was the early 1970s, and Vince “Mac” McKelvey ‘72 came across a role-playing exercise that was happening at UD, run by a group of students called the Peace Studies Institute. He was inspired by the experience and, when Jack Becka ‘72 introduced himself, it was an easy decision to not only get involved, but eventually join Becka as a student co-director. They then met fellow student Wlodarski ‘75 the following year, and the three hit it off. The PSI was housed in a crumbling building called “The Old Women’s Gym,” now the Rike Center. At the time, the wooden second floor of the building, accessed by a rickety staircase, was home to a number of programs focused on various innovative educational initiatives, including Women’s Studies, Interdisciplinary Studies, and Project Interface, a forerunner of community engaged learning.

The Peace Studies Institute had begun with a grant from the Marianists and was run by students under the guidance and inspiration of Brother Leo Murray, who was “our advisor and heavily involved, and was just a great person to be around,” says McKelvey. Brother Leo was involved in Pax Christi, an organization within the Catholic church that prays and advocates for peace. His class in theology inspired many students to work for social justice and engage in nonviolent activism. Associate Provost at the time Jack Nesmith, a proponent of innovation in teaching and learning, supported the development of a number of student-led initiatives, exploring the connection between academics and activism in what was called at the time an “experimental education program”.

“It was a convulsive time,” Becka notes, “and people were very polarized. Coming of age in the 60s, there was a lot going down and you wanted to get involved and do something positive, and keep young men from dying in what we saw as an unnecessary conflict, to do something preventative.” During the Vietnam war, exemptions to the draft were made for those studying in college, which led to a disproportionate number of men drafted whose families couldn’t afford a higher education. Many universities, including UD, required ROTC courses, which many students opposed. McKelvey explains, “In the 60s and early 70s, of course, the Vietnam War was raging and so were anti-war protests. Those issues were front and center; promoting peace and thinking about other ways of doing things was all around us. I was never a political hawk, but neither was I a fervent anti-war protester when I came to UD. I grew to oppose the war as I learned about it and promoting peace always seemed a better way.”

The Peace Studies Institute organized a group of local school teachers and administrators into the Peace Education Task Force to develop a peace education curriculum, “which we viewed broadly to range from self-awareness exercises to interpersonal conflict resolution to international relations,” he says. As part of this task force, McKelvey and Becka were able to teach a peace education course at Julienne High School shortly before its merger with Chaminade. Teaching this course, which Becka says ultimately led to his career in education, was a life-changing experience: “We had an interesting group of kids, everything from daughters of Wright-Patt employees to kids whose brothers were in the war. It was a diverse group that generated lots of discussion. But they were open-ended conversations, not indoctrination.”

The Peace Studies Institute provided students at UD an opportunity to explore these themes of dialogue, nonviolent protest, and conscientious objection under the guidance of faculty members. Within just a few years, around 30 courses were developed with input from students, and made for a vibrant, interdisciplinary effort to explore notions of peace. “I think one way to describe PSI is that it was an effort to bring the subject of ‘peace’ into a formal, college setting,” says Wlodarski, who became the student director of the Institute after McKelvey, “The hope or plan was to have a valid, serious academic discipline within UD's College of Arts and Sciences.” One course, called Parameters of Peace, was offered for three credit hours and used a series of readings which would later become a two-volume anthology of peace literature edited by Wlodarski and James P. Russell titled “A Peace at a Time.” Other mini-course titles were Alternatives to the Draft, The Indochina Peace Campaign, and Spirituality of Nonviolence.

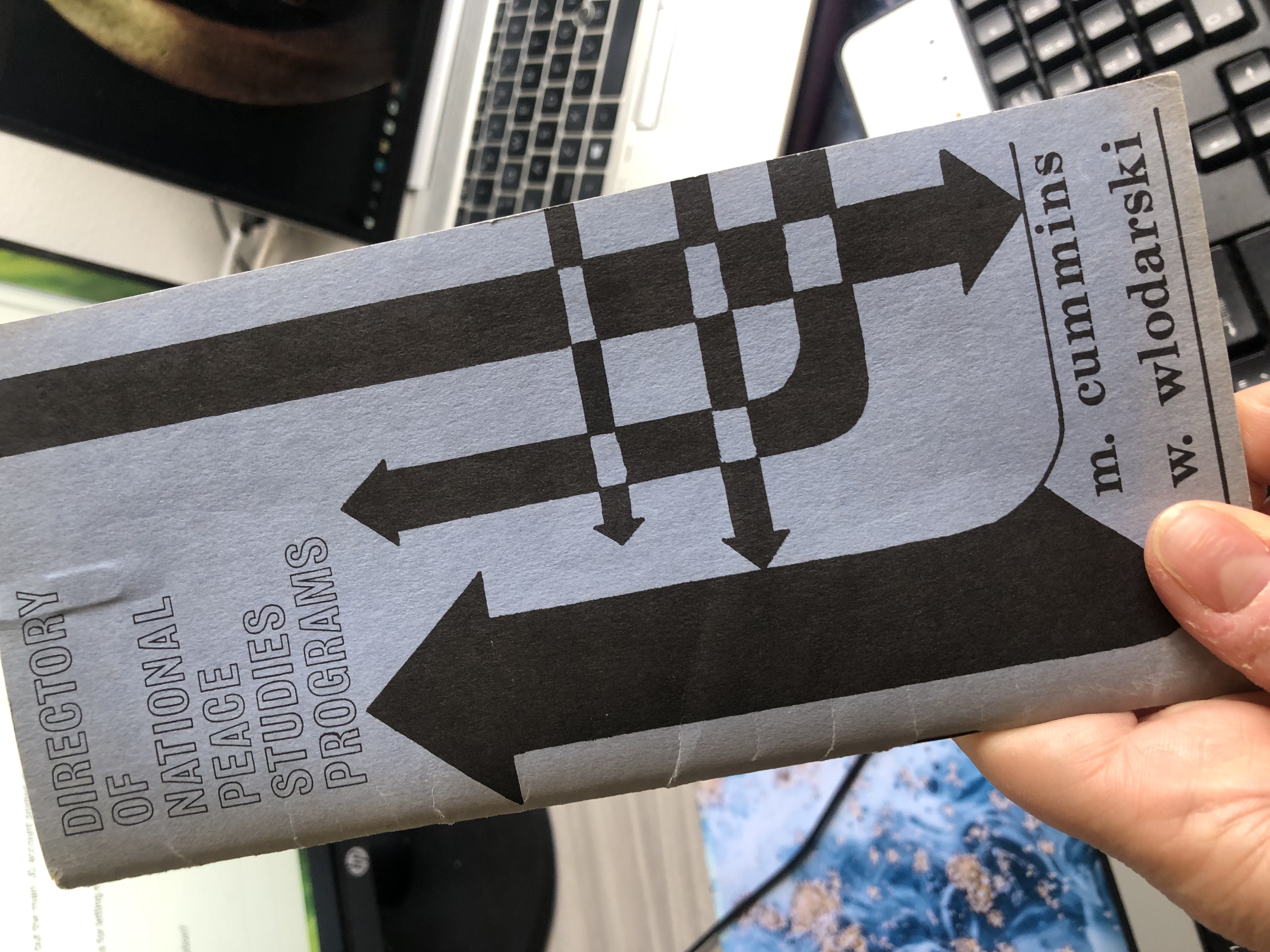

“There was an additional, informal, yet essential component of PSI - that of activism,” says Wlodarski. “There were a fair number of students involved with PSI who often ‘took to the streets’. They were involved in peaceful protests on a variety of social justice issues; for example, the military industrial complex, UD's association with WPAFB and its military research, Vietnam protests, alternatives to the draft and important labor/union rights movements.” This sense of activism was not confined to UD: Wlodarski compiled a directory of national peace studies programs, published in 1974 by the Institute, along with fellow student Mary Cummins ‘75, who would later become his wife. A concern for social justice issues like peace was widespread across the nation at that time, and academic offerings at many institutions reflected that. “Fifty years later,” Becka muses, “we are concerned with a lot of the same issues.”

Years later, in 2019, The Dialogue Zone was established at UD, and reflects some of the same traditions of the Peace Studies Institute and the Peace Education Task Force. The DZ seeks to build capacity among students, staff, and faculty to learn and practice facilitated dialogue in order to address difficult issues that arise as we interact together in community. Dr. Jason Combs, Coordinator of the Dialogue Zone and Principal Lecturer in the department of Communication at UD, notes that there are many connections between the work of the dialogue zone and the peace efforts of the early 70s. “Dialogue involves a different way of approaching the other person. Understanding must come first, and we must seek it for its own sake, not as merely a means to an end. If we understand each other, then perhaps we will have a more adequate foundation on which to undertake common action and to seek common goals.” The DZ trains facilitators on campus to help students, faculty, and staff engage in dialogue in ways that are productive, building capacity for sustained conversations on campus and beyond. Combs adds, “All the people who are drawn to our programs seem to share a recognition that conversations oriented towards understanding rather than polarized and often aggressive debate that is focused only on ‘winning’ are a pressing need in the world right now.”

Seeking peace may look somewhat different in today’s hyper-connected world, says Combs, but the ultimate goal is the same: “Dialogue provides a non-antagonistic alternative for exploring difference. In dialogue, participants seek an understanding of people's experiences, strive to listen to and learn from each other's stories, and to bring to the surface and appreciate the often deep emotions behind the positions that people take regarding controversial or divisive issues.”

What, in the end, was the impact of the Peace Studies Institute? All of the alums credit their work with the PSI in helping shape their eventual careers, sometimes drastically. “It’s hard to say which seeds you plant will grow, but there’s still plenty of conflict in the world,” says Becka. “Discussion has gotten coarser during my lifetime. At some level you have an impact on the students you taught and influenced along the way. On a societal level—I think we’re still struggling to be better people and find our better angels.”

Special thanks to Wayne Wlodarski ('75), Jack Becka ('72), Vince "Mac" McKelvey ('72), and Mary Cummins Wlodarski ('75) for their assistance with this story.