College of Arts and Sciences Newsroom

University of Dayton Russian instructor translates letters written by her father, a Red Army soldier, from the front during WWII

By Dave Larsen

Translating Russian texts to English is nothing new for Tatiana Liaugminas, who has taught Russian at the University of Dayton for more than 40 years. But her most recent project was personal — translating recently discovered letters written by her late father, a Red Army soldier, from the front during World War II.

Liaugminas, an adjunct instructor in the Department of Global Languages and Cultures, published a feature article about the letters in the May/June issue of Russian Life, a color bimonthly magazine of Russian culture.

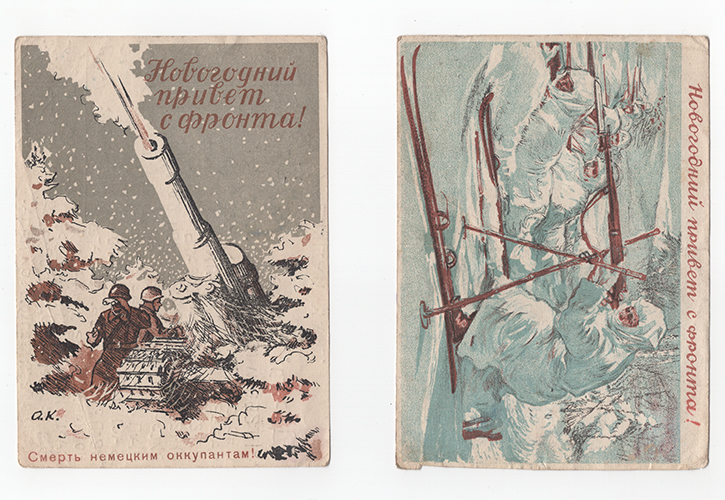

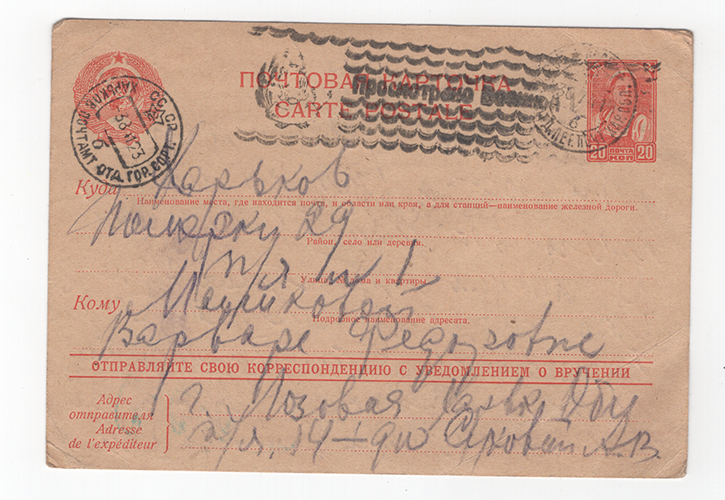

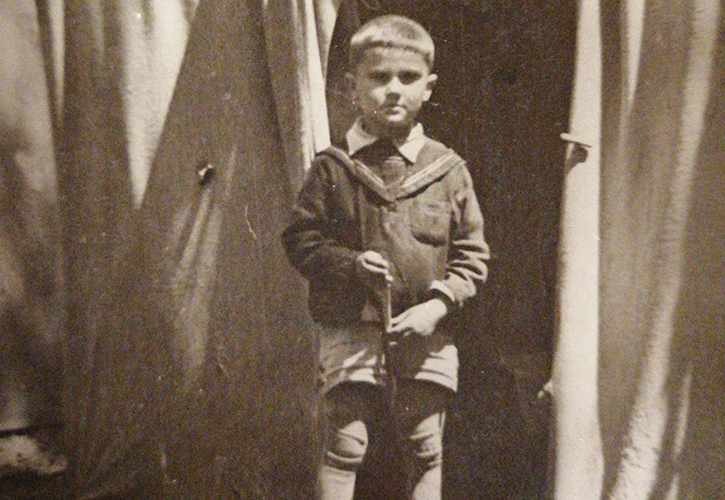

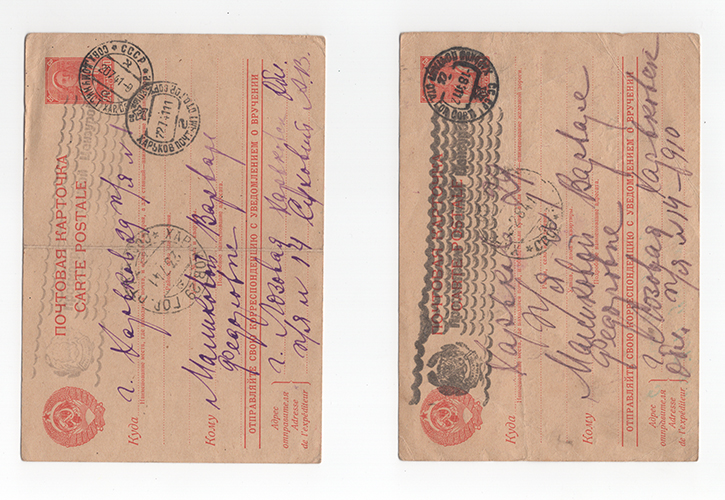

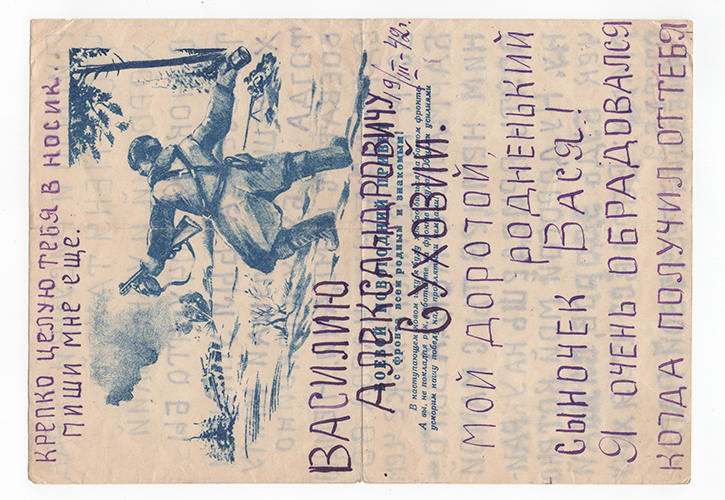

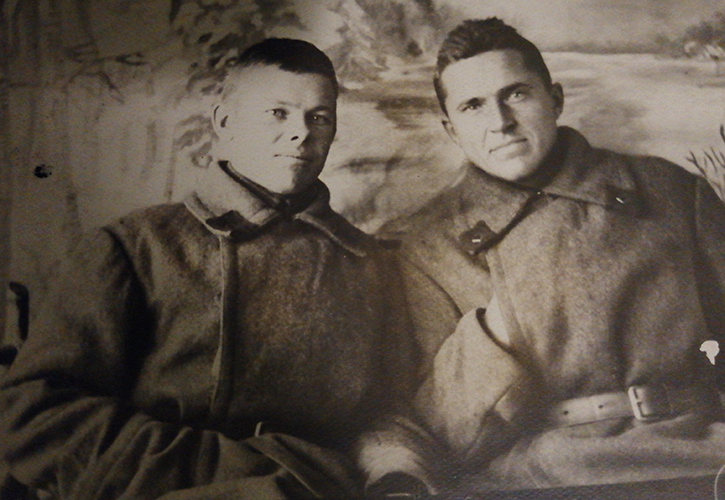

In the 12-page story, Liaugminas recounted how the packet of 11 letters and 12 postcards — written 80 years ago by her Ukrainian father, Alexander Suchovy, to his first wife and son — were found and subsequently sent to her in Dayton. The story included her translations of some of his cards and letters, along with family photos and postcards illustrated with battlefield images and slogans.

Liaugminas said it was “serendipity and sheer luck” that the letters got to her. She received them in May 2020, after learning of their existence from her niece, Julia, in Kharkov, Ukraine. Julia is the daughter of Liaugminas’ half-brother Vasily, who died in 2019. His widow, Louisa, found the letters and didn’t know what to do with them.

“This whole thing is absolutely incredible because I didn’t know anything about these people,” Liaugminas said. “For years, my father never talked about that family, until he found them in 1970, because when he ended up outside of the Iron Curtain, that whole part of his life was completely cut off. There was no way for him to go back and he didn’t want in any way to harm his son – but, as it turned out, it was too late. Vasily was in fact harmed because it was known that (Alexander) had been a prisoner of war and he, of course, never returned.”

Returning to the Soviet Union was not an option for Red Army soldiers who survived the war as POWs. They were considered traitors, and were sent to Siberia or executed. Instead, Alexander remained in Germany, where he met and married a fellow Ukrainian refugee in 1944. Their daughter, Liaugminas, was born in 1945 as the war was winding down. The family ended up at a displaced persons camp in Germany.

“After that, we just meandered throughout the world,” she said. “We went to Belgium and then to French Morocco and then to France and then we came to the United States. Hence, I learned all these languages.”

Liaugminas was fluent in Russian, Ukrainian, French and English by the time she was an adolescent. Her family came to the U.S. in 1958 and settled in a Ukrainian neighborhood in Chicago. She attended the University of Illinois, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in French and Russian, with a minor in Spanish. She also holds a master’s in French and Russian.

She met her husband, who holds a doctorate in aeronautical engineering, when both were graduate students at Illinois. They came to Dayton in 1970, when he took a job at Wright-Patterson Air Force base.

After learning about her father’s wartime correspondence, she asked Julia to scan and send copies of the letters, which described the chaos at the front and expressed his concern for his family. Reading them was “emotional, surreal and at times felt voyeuristic — like uncovering intimate details I shouldn’t know” she said.

She had the actual letters shipped to the U.S. and translated them during the 2020 quarantine. She then reached out to Russian Life magazine editor and publisher Paul Richardson, for whom she previously had written articles. He immediately agreed to publish her story.

“The most amazing thing is not that I got them, but that they had survived 80 years, virtually intact,” Liaugminas said. “This is like gold. People are interested in these things, especially since I got them the day after the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. The whole thing was just serendipity. Like God working — a nod from my dad.”

In recent months, Liaugminas has been translating works by poet Anna Akhmatova for a Russian literature course she will teach during the 2021 fall semester. The course will be taught in English. She previously taught Russian poetry in St. Petersburg, Russia, on study abroad trips led by Russian history professor David Darrow.

“Tatiana has always had an ability to make Russian poetry meaningful to undergraduates at UD,” Darrow said. “The letters and other materials she has acquired — her family archive as she characterizes it — tell a story of hardship and sacrifice during and after the war that, unfortunately, is not uncommon. The history of the Red Army and its soldiers is in the early stages of unfolding as western historians have finally gotten access to needed archives and as family papers like these have come to life.”

For more information, visit the Department of Global Languages and Cultures website.