College of Arts and Sciences Newsroom

Arctic Ice Research

University of Dayton doctoral student Ming Gong '15 is more comfortable at the keyboard of a computer or piano than trekking across snow and ice in sub-freezing temperatures. But, during May and June, she spent 10 days at a field summer school in Utqiagvik, Alaska, where she learned how to collect physical data in the Arctic.

Gong, an electrical engineering student from Shanghai, China, was one of 15 graduate and postdoctoral students who participated in the Arctic research program in Utqiagvik, the northernmost city in the United States. Formerly known as Barrow, it is located about 1,300 miles south of the North Pole.

The Arctic field summer schools project is a three-part research and education collaboration among the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the University of Calgary in Canada and the University of Tromso in Norway. The project allows students from all three nations to get field experience in the physical Arctic environment, gain hands-on knowledge on how measurements are performed to support scientific questions, and learn how environmental changes can be studied and measured through the use of advanced remote sensing technologies.

“This is the first time a UD graduate student has taken part in such an event,” said Ivan Sudakow, assistant professor of physics. “I consider her acceptance into this very competitive program as a great recognition of our efforts in the study of Arctic climate change.”

Gong is a graduate assistant in Sudakow’s research laboratory, where she analyzes the geometry of Arctic tundra lakes, using historical maps and satellite imagery.

Sudakow specializes in the mathematical modeling of physical and living systems. In 2013, he was named “Green Talent” by the German government for his sea ice research and strong commitment to transdisciplinary interaction between mathematics and climate science.

In Utqiagvik, Gong learned synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) imaging, which can be used to create three-dimensional reconstructions of landscapes. She employed the technology to classify various types of sea, lake and tundra ice in that region.

Gong and her fellow students then traveled to 10 random points to test the accuracy of her classification results against the actual ice at those locations. They verified her findings with 80 percent accuracy, a high success rate.

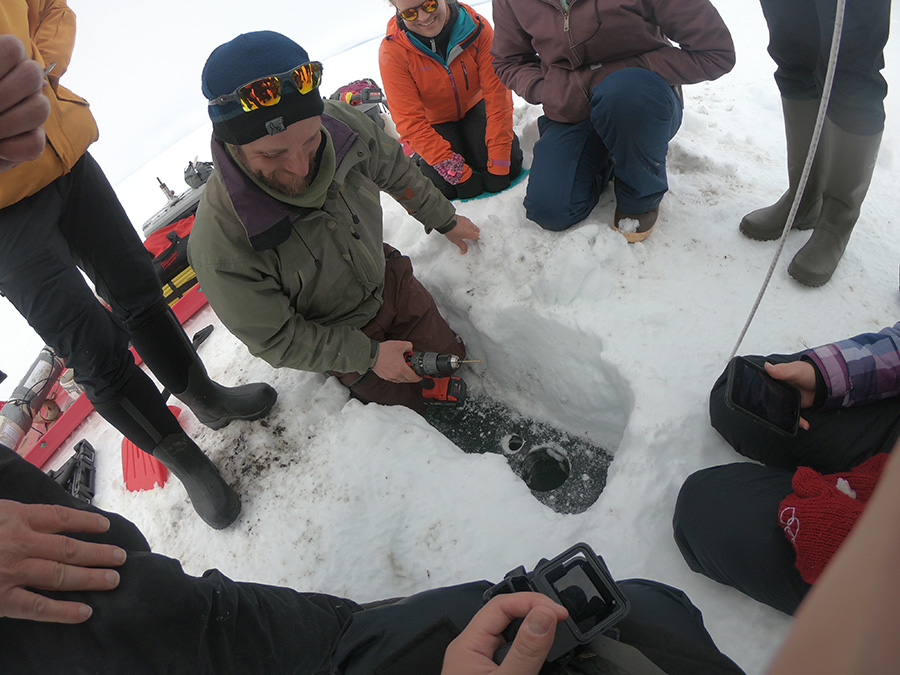

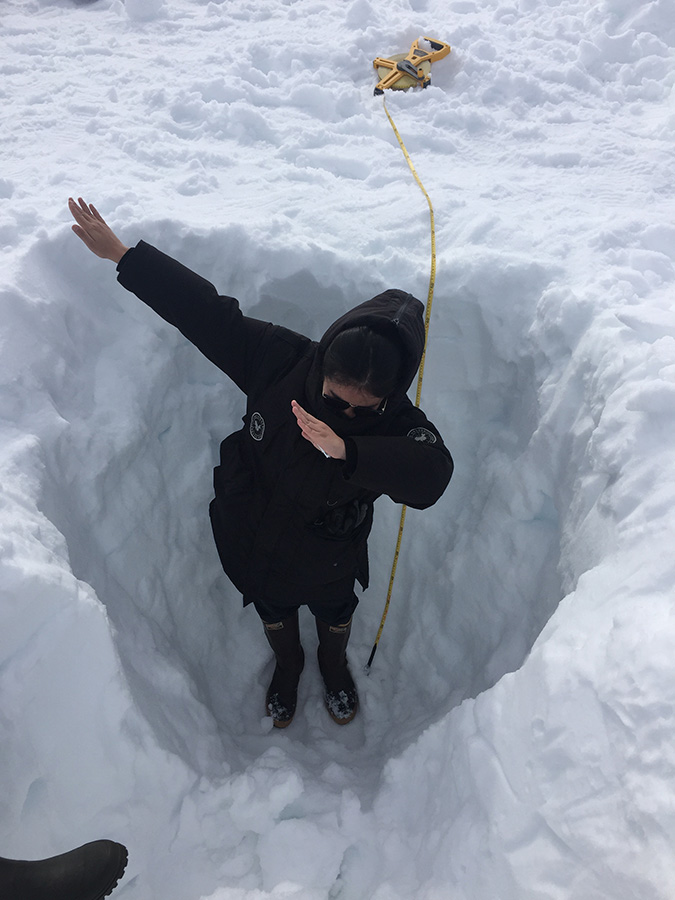

“Most of the time we went into the field and did a lot of experiments,” Gong said. “We measured snow depths and ice depths. We took a lot of ice cores, and cut them into pieces and brought them to the lab to test how salty they were.”

The students stayed in a dormitory at the Barrow Arctic Research Center and spent five to six hours each day in the field. They traveled across sea ice by snowmobile and on foot, accompanied by advisors and an armed guard to protect the team from bears. The guard stopped one excursion after polar bear prints were seen in the snow.

Average May temperatures in Utqiagvik range from 16 to 26 degrees Fahrenheit.

“It was cold,” Gong said. “The first day, someone told me to just wear as much as you could, so I wore two pairs of socks. When in the field, I could not feel my feet after one hour. The second day I wore four pairs — still super cold. So, I wore all of them, like six pairs of my socks. It was OK, but I still felt cold.”

She also experienced 24-hour sunlight, which made it difficult to know when to sleep or eat. She wore sunglasses, and used her phone to keep track of time.

Gong received a bachelor’s degree in engineering technology from the University of Dayton in 2015 through a dual degree program with Shanghai Normal University, from which she also received a bachelor’s in electronic engineering. Currently, she is completing her master’s thesis and is enrolled in the doctoral program.

She specializes in computer vision, signal processing, machine learning, image processing and linear control systems.

Sudakow said such skills are needed to study the processes underlying Arctic system change and to assess their global environmental and economic impacts. In October, the National Science Foundation announced a new program, Navigating the New Arctic, which seeks to better understand Arctic change by bringing together diverse disciplinary perspectives to support convergence research.

“The goal is collaboration across disciplines because Arctic research is quite complex and should involve different sciences, from theoretical physics and applied mathematics to the social sciences, to see the wide picture of what is going on with natural, social and cultural systems in the Arctic and to create a good future for this region,” Sudakow said. “Engineering like Ming is doing — machine learning and data and image analysis — is an important part of this new strategy.”

- Dave Larsen, communication coordinator, College of Arts and Sciences