College of Arts and Sciences Newsroom

Making a Difference

"I got a job today," she said. "And I got offered a place to live."

Inside the St. Vincent de Paul homeless shelter in Dayton, a small group of women cheered those two life-changing sentences.

It was the start of a support group meeting led by University of Dayton students in a small room decorated with handmade paper stars hanging from the ceiling and completed puzzles taped to the walls.

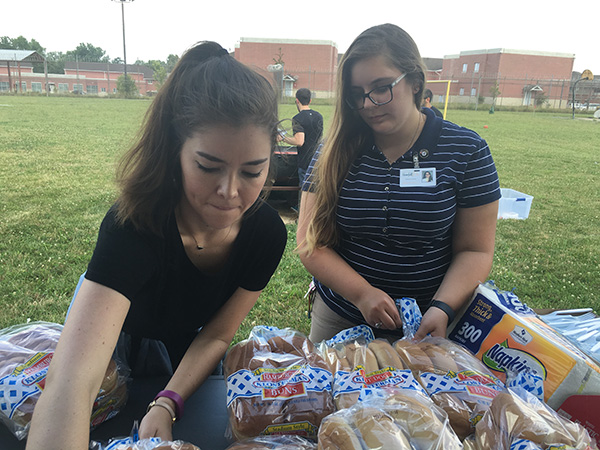

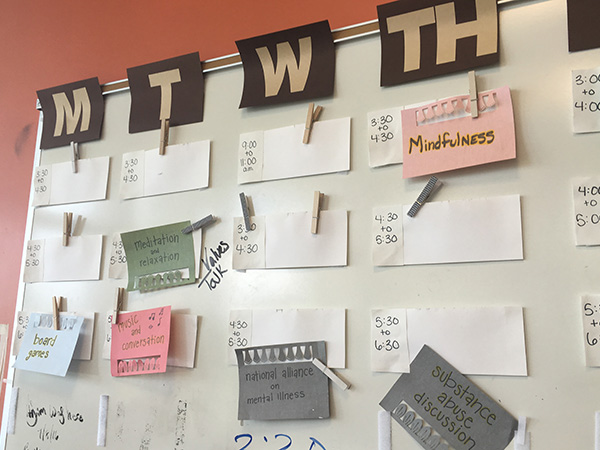

The students are there five days a week to offer help managing stress, training on computers and preparation for the GED, as well as recreational sessions often involving art or music.

Their immediate aim: empower the women, enhance their coping abilities and improve the social climate of the shelter. Across town, they have the same goals for the Gateway Shelter for Men.

Their work is led by University of Dayton psychology professor Roger Reeb as part of his research on “behavioral activation” — the idea that a program or experience can improve someone’s thoughts, mood and behavior, and help them to recognize and pursue opportunities in the future.

“The goal is lasting change,” said graduate student Bernadette O'Koon.

That lasting change is for shelter guests to ultimately find housing and employment, and transcend homelessness.

‘Rays of hope’

The project started four years ago when Reeb, a licensed clinical psychologist who is the University’s Roesch Endowed Chair in the Social Sciences and a research associate in the Human Rights Center, formed a partnership with David Bohardt, executive director of St. Vincent de Paul. The two wanted to find a way to decrease the stress of shelter life, improve coping skills of shelter guests, and ultimately improve job and housing retention rates — all while also dealing with constrained resources.

St. Vincent serves more than 100,000 people each year — 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

The shelters offer temporary emergency housing for as many as 400 men, women and children on any given night. The nonprofit also provides food, showers, clothing and a caseworker to help each person or family secure a permanent place to live.

The guests regularly move on, but Bohardt said 40 percent return within two years. He noted that most people at his shelters face challenges with employment. Bohardt estimates that at these two shelters about 60 percent self-report mental illness, 40 percent suffer from drug or alcohol abuse and at least 30 percent have criminal histories, often involving past incarceration.

“Given the life experiences of our clients, the baggage they carry, the very high bar to qualify for mental health services, their job skill deficits, the complication of children, their continuing struggles with the demons of alcohol and drug abuse, and incredibly complicated and often non-supportive families, we can ask: What service or program, given our cost constraints, is our best opportunity to improve client outcomes,” Bohardt said. “The answer is behavioral activation.”

Bohardt recently collaborated with Reeb and his students to present the findings of this project at the International Association for Service-Learning and Community Engagement in Boston.

He said the students can be “rays of hope.”

Twenty to 30 students — and sometimes more — participate in a semester supervised by Reeb and a number of graduate students. The undergraduates said they are inspired by the interactions, too.

“I’ve realized how similar we are,” said Nate Bloss ‘16, who now holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology. “It’s just the circumstances they were given that led them here.”

Bloss admitted he was intimidated the first time he entered the men’s shelter, which is housed in a former prison building still surrounded by barbed wire fencing and guard towers. But soon, any stigma he had of the people inside lifted.

He said he will always remember meeting a gentleman sitting in the corner reading a book. In their conversations, he learned the man knew three languages and often quoted poets.

“I would be kind of embarrassed because I didn’t know the poets,” Bloss said with a smile. “Then one day, he wasn’t there anymore. He worked hard to move on. He deserved it.”

Lizzy Miller, an undergraduate studying early childhood education, also said she was struck by how much she found in common with the men. She loves to draw, and one man she often spent time with was exceptional at it. She wants to be a first-grade teacher and he was working to get a job, as well.

“We’re both trying to figure out how we can get to the place we want to be,” she said. “We can share how our day has been going and we can also play a boardgame to forget everything for a moment.”

‘A place of opportunity’

Reeb said the project is about making each shelter a “place of opportunity” instead of one of despair. On any given day, students do so through casual conversations or rounds of cards. They might offer a stress management session to relieve anxiety and improve coping skills. Or refer someone to a much-needed resource in the community, such as the free clinic. Or work with someone on creating a resume or applying for a job.

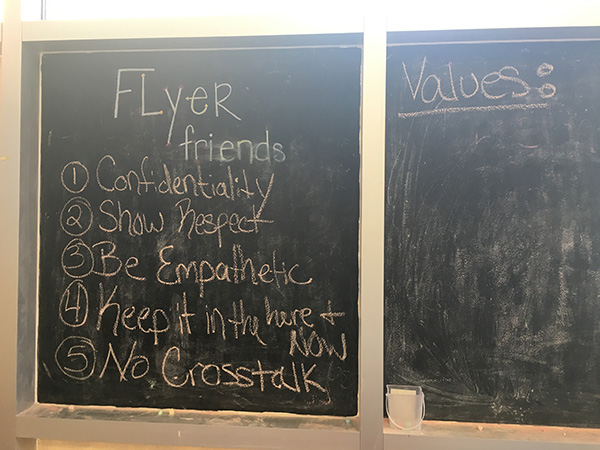

Their interactions are guided by the shelter guidelines of respect, empathy and confidentiality. When students meet someone, that person might have been staying at the shelter for just hours or for several days. It might be their first time there or their sixth stay.

“The shelter guest might say of a student: ‘He seems like a nice guy. He won’t judge me. He can help me to help myself.’ Then, that person is not waiting on the system for help, but he or she is actively working with our students to pursue opportunities,” Reeb said.

Students, who come from a wide variety of majors, including social sciences, engineering, education and pre-medicine, prepare for the experience in Reeb’s class, Engaged Scholarship for Homelessness: A Service-Learning Course. They learn safety procedures and review St. Vincent’s code of conduct. Reeb tells them they are research assistants and not volunteers, and the project does not end at the end of the semester. It goes year-round, including summers and holiday breaks. Some students continue with it for the remainder of their undergraduate careers.

Their efforts are supported by partnerships Reeb has formed over the years. Reeb’s primary community partner, Bohardt, has been involved at every phase of the project, including conceptualization, planning, implementation and evaluation — a hallmark of “Participatory Community Action Research,” which aims to improve communities through social change.

Reeb’s efforts also included installing a computer lab in each shelter to allow guests to work with students on job searches, resume building, GED training and other sessions that empower them as the strive to transcend homelessness.

Examples of other campus-community partners include the Homeless Solutions Board of Montgomery County, the Montgomery County Office of Ex-Offender Reentry, the National Alliance on Mental Illness of Montgomery County, and the University’s Fitz Center’s Youth Economic Self Sufficiency Program.

In his collaboration with the Montgomery County Office of Ex-Offender Reentry, Reeb was able to secure a matching funds arrangement to support a full-time staff member to connect the services of the behavioral activation project with those of the reentry program.

The rationale for this collaboration: A significant percentage of homeless individuals have a history of incarceration; a criminal background and incarceration create major barriers to obtaining employment and housing; a background of homelessness is prevalent among individuals in prison; and individuals released from jail or prison to homeless shelters are at a particular risk for recidivism. This particular collaboration involves Judge Walter Rice; Joe Spitler, criminal justice director for Montgomery County; and Jamie Gee, manager of the Montgomery County Office of Ex-Offender Reentry.

“For guests at the shelter, involvement with the Office of Reentry’s program and services seems to have an unprecedented effect on them,” said Charles Hunt, a postgraduate research assistant in community engagement. “It grants them access to resources and community partners who are willing to overlook someone’s past and judge them based on what they are doing in the present. This fills them with a great sense of personal pride and confidence to continue struggling in a world that is stacked against them.”

The future

The project results are positive thus far, according to data gathered by students through surveys and analyzed by Reeb’s colleague, Greg Elvers, associate professor of psychology at the University of Dayton.

More than 1,000 men and women at the shelters have participated in the project. Shelter guests rate the programs as important, meaningful, worth repeating and enjoyable.

Surveys also collect data along the way to assess whether the behavioral activation sessions are viewed by shelter guests as improving their hope, mood, empowerment (and motivation for work or education), social/emotional support, purpose or meaning in life, and quality of life. The data suggests guests do indeed perceive the sessions as helpful in these ways. This psychological measurement data is supplemented by qualitative comments shelter guests provide on surveys.

For example, one guest wrote:

"UD students (have) been an incredible help to me — helping me get myself together. This whole program has truly been a blessing. Because of these amazing people I'm going to counseling again, I'm in college and I'm doing a heck of a lot better than I was. I'm very grateful for all of their help."

Reeb is also monitoring the impact on the students. His research suggests by the end of a semester, those involved experience decreases in their tendency to stigmatize and increases in “community service self efficacy,” or their beliefs that they can make a difference in the community. They also gain a greater awareness of their own privilege.

Reeb has presented his results so far at local, national and international conferences. In addition, the project is featured in a number of chapters in a recent book coauthored by Reeb and published by the American Psychological Association, Service Learning in Psychology: Enhancing Undergraduate Education for the Public Good.

In the next phase of the project, Reeb and Bohardt hope to follow as many people as possible as they leave the shelter to track their employment and housing situations. Reeb hopes to compare their outcomes to people who stayed at the shelter but did not participate in the behavioral activation, people who stayed at the shelter before the project began, and people at similar shelters in other areas.

"If we can prove our efforts made a difference here, we can offer a model for homeless shelters in other communities,” Reeb said.

Reeb said the project will continue indefinitely.

“People ask, ‘When will your project end?’” Reeb said. “I laugh and say, ‘Whenever I don’t have students who are interested or other necessary resources. Or when homelessness ends in Montgomery County.’ Why would I ever end it, if I have the possibility of helping people?”

- Meagan Pant, assistant director, University News and Communications